0..5/+%#4+0/30(4*'330%+#4+0/(02/(02.#4+0/834'.30..5/+%#4+0/30(4*'330%+#4+0/(02/(02.#4+0/834'.3

"0-5.' #1'2

*'0-'0(2)#/+9#4+0/#-42#4')8+/4*'!3'2%'/4'2'&'3+)/ *'0-'0(2)#/+9#4+0/#-42#4')8+/4*'!3'2%'/4'2'&'3+)/

0(0$+-'11-+%#4+0/30(0$+-'11-+%#4+0/3

8#-3*'4

;$0,#&'.+!/+6'23+48

''3*'4#$0:

#2,&''56'2

'-(4!/+6'23+480( '%*/0-0)8

#228057.#/

'-(4!/+6'23+480( '%*/0-0)8

0--074*+3#/&#&&+4+0/#-702,3#4*4413#+3'-#+3/'402)%#+3

'%0..'/&'&+4#4+0/'%0..'/&'&+4#4+0/

3*'4&''56'2057.#/ *'0-'0(2)#/+9#4+0/#-42#4')8+/4*'!3'2%'/4'2'&

'3+)/0(0$+-'11-+%#4+0/30..5/+%#4+0/30(4*'330%+#4+0/(02/(02.#4+0/834'.31111

*4413&0+02)

*+3.#4'2+#-+3$205)*440805$84*'052/#-3#4-'%420/+%+$2#28'4*#3$''/#%%'14'&(02

+/%-53+0/+/0..5/+%#4+0/30(4*'330%+#4+0/(02/(02.#4+0/834'.3$8#/#54*02+9'&#&.+/+342#4020(

-'%420/+%+$2#28'02.02'+/(02.#4+0/1-'#3'%0/4#%4'-+$2#28#+3/'402)

C

ommunications of the

A

I

S

ssociation for nformation

ystems

Research Paper ISSN: 1529-3181

Volume 40 Paper 14 pp. 315 – 331 April 2017

The Role of Organizational Strategy in the User-

centered Design of Mobile Applications

Eyal Eshet

Turku Centre for Computer Science (TUCS)

Faculty of Social Sciences, Business and Economics, Åbo Akademi University, Finland

Mark de Reuver

Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, Delft

University of Technology, The Netherlands

Harry Bouwman

Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, Delft

University of Technology, The Netherlands

Abstract:

Gathering insights on users and the contexts they use mobile applications is at the core of the user-centered design

(UCD). Organizations find it strategically important to efficiently and effectively use these insights. With the

proliferation of mobile applications, gaining timely and relevant insights is increasingly challenging due to the

heterogeneous and dynamic context of use, the abundant availability of information on use behavior and the intense

time constraints imposed by the highly competitive mobile market. This paper develops a research model that

considers strategy foci as motivators that affect the efficient and effective use of insights on users and context in

design practices. We examine the mediating effects of UCD resources, such as time and financial constraints,

organizational practices, and UCD competence. To test the model, we conducted a survey with 100 mobile

practitioners and used PLS to estimate the model. The model shows that focus on an innovation strategy both directly

and indirectly affected data use on user and their context (i.e., mediated by organizational practices and UCD

competence) in design practices. Strategies with a focus on cost had no direct effect on the use of user insights but

led to negative impacts on UCD competence and organizational practices.

Keywords: IS Development, Organizational Strategy, Mobile Applications, Interaction Design, Survey.

This manuscript underwent editorial review. It was received 02/02/2016 and was with the authors for 7 months for 1 revision. Anders

Hjalmarsson served as Associate Editor.

316 The Role of Organizational Strategy in the User-centered Design of Mobile Applications

Volume 40 Paper 14

1 Introduction

User-centered design (UCD) is a well-established approach to designing and developing usable and

useful interactive systems. According to the approach, insights on users and their use contexts largely

inform how one should design interactive systems. Gaining these insights is strategically important to

organizations, which one can see in research in various disciplines such as management information

systems (MIS) (Robey & Markus, 1984), strategic management (Boland, 1978), software engineering

(Schmidt, Lyytinen, & Mark Keil, 2001), human-computer interaction (Gould & Lewis, 1985), the emerging

disciplines of user experience (UX) design (Hassenzahl & Tractinsky, 2006) and interaction design

(Sharp, Rogers, & Preece, 2007), and international standards (ISO, 2010). Commonly, organizations use

an idiosyncratic approach to collect and analyze user data. Regardless of the approach, organizations

need to efficiently and effectively use this data (the dependent variable in our research) in their projects.

As such, the way organizational strategies are implemented in working and, therefore, also in design

practices have an impact on the use of data in design practices. Understanding the influence of different

strategies and work procedures on the UCD practice is relevant to IS design management.

The new mobile era, labeled the “mobile apps era” (Eshet & Bouwman, 2015), introduces challenges to

the UCD practice of mobile interactive systems (i.e., mobile applications), specifically regarding designers’

effort to gain relevant insights on users and their use contexts. In contrast to the typically single use

context in stationary computing (e.g., desktop and Web applications), mobile computing devices such as

smartphones feature multiple use contexts (Henfridsson & Lindgren, 2005). In addition, the affordability of

mobile devices leads to more diverse users and new classes for situated activities that mobile computing

makes possible (Johnson, 1998). Consequently, users’ diversity and their variety of use contexts strain

efforts to effectively collect and analyze relevant user data. Secondly, rapid technological developments in

recent years (e.g., in embedded sensors and wireless technology) allow one to collect and analyze actual

use behavior data in real time. In particular, “big data” has led to a continuous flow of data about users’

behaviors, which insights from a growing number of market research companies has further fueled. With

the excess availability of use data, the efficient use of insights the data provide (i.e., understanding the

relevant from the ordinary) becomes more difficult. Lastly, application stores such as those that Apple and

Google provide have democratized the development and distribution of mobile applications, which has

resulted in an increasingly competitive and dynamic mobile market (Bergvall-Kåreborn & Howcroft, 2011).

Moreover, developers have increasingly begun to adopt agile approaches to design and develop mobile

applications (Eshet & Bouwman, 2015), though the agile principle on short system-delivery cycles limits

the time one has to understand users (Seffah, Desmarais, & Metzker, 2005). Given the competitive

pressures and resource constraints for UCD practice, effectively and efficiently using user and context

data becomes more strategically important.

To our knowledge, research has not examined organizational strategy and its relation to a specific aspect

in the UCD practice of mobile applications; that is, efficiently and effectively using data on users and their

use contexts. The new mobile era introduces challenges beyond “bring-your-own-device” (BYOD) or

channel strategies, affecting a company into its capillaries. We need to understand how an outside-in

perspective on organizational strategies (De Wit & Meyer, 2010) combines with an inside-out strategies

focused on providing resources and building competence in order to support the UCD practice. From an

outside-in perspective, views on cost-focused strategies vis-à-vis strategies focused on innovation are

relevant to consider (Christensen, 1997; Porter, 1985; Tidd, Bessant, & Pavitt, 2005). From an inside-out

perspective, the availability of UCD resources and capabilities, as extensively discussed in strategic

management and IS literature, needs attention (Barney, 1991; Mata, Fuerst, & Barney, 1995; Wernerfelt,

1984). Research on the relation between IS and resources and capabilities are rather high level and focus

in a generic way on IT assets, IT processes, or IS capabilities (Wade & Hulland, 2004) rather than on

specific practices. IS research has paid extensive attention to “design science” (Cross, 2001; Hevner,

March, Park, & Ram, 2004; Peffers, Tuunanen, Rothernberger, & Chatterjee, 2007; Sein, Henfridsson,

Purao, Rossi, & Lindgren, 2011), though we have yet to see IS research on organizational strategy’s

effect on the UCD practice. Research in human-computer interaction (HCI) emphasizes the relation

between the UCD practice and UCD resources/competence; it also emphasizes management-level

support (e.g., Rosenbaum, Rohn, & Humburg, 2000; Venturi, Troost, & Jokela, 2006), though it has yet to

establish a relation between organizational strategy and the UCD practice. With the increasing dominance

of mobile-based applications and big data’s emergence, attention to the UCD practice is important.

As such, in this study, we examine the impact of organizations’ strategies on the UCD practice. Given the

abundant available data on users and their use contexts, we focus on how innovation- and cost-focused

Communications of the Association for Information Systems 317

Volume 40 Paper 14

strategies affect a specific aspect of the UCD practice (i.e., using data about users and their use contexts

efficiently and effectively to design and develop mobile applications). Moreover, following HCI-based

views on the UCD practice, we examine the relation between organizations’ strategies and the UCD

practice using UCD resources and competence and organizational practices as mediating effects. As

such, this paper contributes to how time and financial constraints, UCD capabilities, and organizational

practices mediate the relationship between organizational strategy and how effectively and efficiently

organizations use data about users and their use contexts. We also contribute to strategic management

literature and to “design science” approaches in IS by connecting a strategy focus with the UCD practice

of mobile applications. As far as we are aware, no quantitative research that focuses on this relation

exists.

We surveyed user experience (UX) designers and interaction designers, software developers, project

managers, and project owners who are active in the design and development of mobile applications to

collect their perceptions and views. The study was carried out when the use of mobile applications

became a common practice in work and non-work activities of people in many western countries.

Research relating organizational strategic aspects to the UCD practice is limited and important for

managers to see what implications their strategic decisions have on the way mobile applications are

designed and to what degree design practices take insights based on use data and on context of use into

account. By doing so we also relate IS research with a focus on strategy to research on the UCD practice

in HCI.

This paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2, we define the core concepts of the paper and develop

hypotheses based on relevant literature. We also provide a research model. In Section 3, we explain the

overall research methodology. In Section 4, we present the study results and, in Section 5, discuss the

results. Finally, in Section 6, we discuss the study’s limitations, suggest future research directions, and

conclude the paper.

2 Core Concepts and Hypotheses Development

2.1 Core Concepts

2.1.1 UCD Practice

UCD is a formalized and standardized approach (ISO, 2010) to the designing and developing usable and

useful interactive systems. According to the approach, to develop usable and useful interactive systems,

one needs focus on users and their use contexts throughout the design and development process.

Practically, this focus is operationalized through UCD activities, such as interviews, observation, usability

tests, and market research (Sharp et al., 2007). Hence, UCD practice refers to the set of activities that

help one gain insights on users, their use contexts, and their use behaviors when designing and

developing interactive systems. Individuals involved in UCD practice use many different job titles, such as

interaction designer, user experience (UX) designer, usability engineer, and user researcher (Sharp et al.

2007).

2.1.2 Mobile Application

We consider mobile applications here from a sociotechnical perspective. Socially, mobility is an attribute

of humans rather than applications; as such, we roughly define it as people’s ability to move between

locations that vary spatially, temporally, and socially (Henfridsson & Lindgren, 2005). People carry their

computing devices with them while moving and use the devices in varied multi-contextual settings.

Accordingly, we consider mobile devices here as devices that people carry with them (Dix et al., 2000),

such as smartphones and tablet computers. We define the software programs that run on these mobile

devices as mobile applications. Technically, a mobile application can take the form of a native platform

application (i.e., mobile app), Web-based solution (i.e., HTML5), or any hybrid solution.

2.1.3 Organizational Strategy

Porter (1985) describes strategy in terms of the activities an organization chooses to perform (either

different activities from rivals or similar activities in different ways) in order to withstand competition in the

long run. These activities do not merely support the organization in dealing with the external competition

but essentially guide its and its employees’ internal operations, actions, and behaviors (Mintzberg, 1987).

318 The Role of Organizational Strategy in the User-centered Design of Mobile Applications

Volume 40 Paper 14

In this study, we limit the scope of strategies to two distinct approaches: cost-leadership strategy and

innovation-focused strategy.

2.1.4 Organizational Work Practices

Apart from a strategy, organizations have internal cultures with distinct characteristics that have an impact

on daily work practices, including on the UCD practice (Iivari, 2006). In this study, we consider

organizational culture in terms of established work practices that contribute to creativity, open

collaboration, and the sharing of ideas in the work environment.

2.1.5 UCD Competence

One can describe competence as the qualifications that make someone fit to perform a particular activity

(Ritter & Gemünden, 2004)—in this case, activities that relate to the UCD practice. Hence, UCD

competence refers to the capabilities and experience that practitioners need to deal with the UCD

practice.

2.1.6 UCD Resources

Resources denote everything that an organization controls, such as assets, capabilities, organizational

processes, knowledge, and information, which enable the organization to cost-effectively implement its

strategies (Barney, 1991). In this study, we limit UCD resources to the financial and time resources that

organizations allocate to the UCD practice.

2.1.7 Efficiently and Effectively Using Data on Users and Their Use Contexts

Data on users and their use contexts refers to the insights gained through the UCD practice. In this study,

we use the dependent variable efficient and effective use of this data (e.g., the extent to which the data

provide understanding on users’ use contexts in UCD practice with maximum productivity and minimal

wasted efforts (efficiency) and produce the desired result (effectiveness)).

2.2 Hypotheses Development

2.2.1 Cost-leadership Strategy

One can conceptualize organizational strategy from two perspectives: outside-in and inside-out (De Wit &

Meyer, 2010). Porter’s (1985) approach on strategic positioning is one approach typical for outside-in

views. Porter emphasizes two core types of competitive advantage: cost and differentiation. In

combination with the scope of activities, three strategies are considered: cost leadership, differentiation, or

focus. Treacy and Wiersema (1993) refines Porter’s ideas by focusing on operational excellence, product

leadership, and customer intimacy. In practice, a focus on cost and operational excellence leads to cost

awareness and optimization to reduce costs. Hereafter, we label this strategy “cost-leadership”.

The cost-leadership strategy implies that cost awareness is also key for UCD practice and, hence, that it

affects how an organization collect and uses data about users’ behavior and use contexts. A cost-

leadership strategy would favor using existing secondary data and low-cost alternatives, such as freely

available Internet reports on mobile use, to gain insight on users’ behavior and use contexts. Since no

established theoretical insights on the relation between strategy and the UCD practice exist, we anticipate

that a cost–leadership strategy directly and positively impacts organizations’ ability to efficiently and

effectively use data about users’ and their use contexts in design practices.

Hypothesis 1: Cost-leadership strategy increases efficiency and effectiveness of using data on

users and context of use in design practices

In response to outside-in models, Barney (1991) developed the resource-based view on strategy, by

focusing on how rare resources and capabilities give firms a competitive advantage. Resources and

capabilities that are rare, are hard to imitate, and have limited alternatives reinforce a company’s strategy.

Hence, resources and capabilities play an important role in how firms deal with the critical contingencies

that they face. The competence and experience of UCD practitioners may be part of these critical

resources and capabilities.

In the IS literature, much research has examined resources and capabilities though on a high-level. In this

study, we focus on resource and capabilities that are specifically relevant for the UCD practice. Insights on

Communications of the Association for Information Systems 319

Volume 40 Paper 14

the work of practitioners who deal with the UCD practice show that many resource constraints affect their

work; these constraints include time and money (Monahan, Lahteenmaki, McDonald, & Cockton, 2008;

Rosenbaum et al., 2000; Vredenburg, Mao, Smith, & Carey, 2002), the limited integration of design

practice techniques within an organization (Bygstad, Ghinea, & Brevik, 2008; Gulliksen, Boivie, &

Göransson, 2006), organizational culture (Iivari, 2006), organizational work practices in terms of internal

communication (Rosenbaum et al., 2000; Venturi et al., 2006), and management support (Gulliksen et al.,

2006; Rosenbaum et al., 2000; Venturi et al., 2006). In addition, designers’ competence (skills and

expertise) is an important element to consider (Hertzum & Jacobsen, 2001; Gulliksen et al., 2006; Suwa &

Tversky, 2001).

In this study, we consider the concepts of organizational work practices, UCD competence, and UCD

resources. We propose that they mediate the relation between organizational strategies and how

effectively and efficiently designers uses data on users and their use. Stimulating creative- and

collaboration-focused work practices requires significant time and budget resources and particular skills.

Existing HCI studies mainly highlight the challenges in promoting and implementing UCD activities in

organizations (Gulliksen, Boivie, Persson, Hektor, & Herulf, 2004; Rosenbaum et al., 2000; Venturi et al.,

2006) and provide guidelines for dealing with the institutionalization of the UCD practice (Mayhew, 1999;

Schaffer, 2004). As such, since we could find no existing literature in this area, we formulate our

hypotheses based on generic insights from innovation literature relating to business strategy.

With regard to organizational work practices, we anticipate that a cost-leadership strategy will more highly

regulate organizational work practices, which will leave less room for creativity, open collaboration, and

the sharing of ideas.

Hypothesis 1a: Cost-leadership strategy decreases organizational work practices committed to

UCD.

Similarly, we anticipate that cost-leadership strategy will have a negative effect on UCD resources and

UCD competence.

Hypothesis 1b: Cost-leadership strategy decreases resources committed to UCD.

Hypothesis 1c: Cost-leadership strategy decreases UCD competence

2.2.2 Innovation-focused Strategy

Similarly to Porter’s (1985) differentiation strategy and Treacy and Wiersema’s (1993) product leadership

view, emerging and transformational strategies (Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, & Lampel, 2009) that focus on the

impact of disruptive or incremental innovation (Christensen, 1997; Tidd et al., 2005) adopt an outside-in

approach. These strategic approaches all similarly dictate how companies and organizations should

respond to changes in their external environment, such as technology innovation or changes in consumer

demand or competitor behavior. We label these approaches “innovation-focused” strategies in this paper.

The changes in consumer demand and behavior with regard to mobile applications, may affect an

organization and require a response from top-management (e.g., offering new products and services).

In innovation-focused strategy, using UCD activities requires engaging users in depth, such as by

conducting contextual interviews, observing users, conducting focus groups, and analyzing data about

users collected via device-embedded sensors. In principle, these activities require much time and many

resources and are, therefore, less effective and efficient. Therefore, we anticipate that innovation-focused

strategy will have a direct and negative impact on the efficient and effective use of data on users and

context of use:

Hypothesis 2: Innovation-focused strategy decreases efficiency and effectiveness of using data on

users and context of use.

With regard to the mediating concepts of organizational work practices, UCD competence, and UCD

resources, we anticipate that an innovation-focused strategy will leave more room for creativity, open

collaboration, and the sharing of ideas and have a positive impact on the availability of UCD resources

and UCD competence.

Hypothesis 2a: Innovation-focused strategy increases organizational work practices committed to

UCD

Hypothesis 2b: Innovation-focused strategy increases resources committed to UCD

320 The Role of Organizational Strategy in the User-centered Design of Mobile Applications

Volume 40 Paper 14

Hypothesis 2c: Innovation-focused strategy increases UCD competence

2.2.3 UCD Resources

Applying UCD activities to gain understanding on users and their use contexts depends on the availability

of financial and time resources. Several studies have observed that budget and time constraints have a

significant influence on the UCD practice (e.g., Monahan et al., 2008; Rosenbaum et al., 2000;

Vredenburg et al., 2002). These resources may have a determinant role on the approach that practitioners

take during the UCD practice, such as how much effort, if any, they put into undertaking user and context

studies and how evaluation of design artefacts is carried out. Thus, we anticipate that the availability of

UCD resources will have a direct and positive impact on the efficient and effective use of data on users

and context of use in UCD practices.

Hypothesis 3: The amount of resources committed to UCD increases efficiency and effectiveness

of using data on users and context of use.

On a more general level, one can assume that UCD resources also impact UCD competence and

organizational work practices. Having a higher budget and more time also implies that one will have more

opportunities to develop one’s UCD competence, to pay attention to new ideas and feedback, and to work

in teams. Therefore, we anticipate that UCD resources will have a mediating roles between strategy

orientations (cost leadership or innovation focus) and (1) organizational work practices and (2) UCD

competences.

Hypothesis 3a: The amount of resources committed to UCD increases organizational work

practices committed to UCD.

Hypothesis 3b: The amount of resources committed to UCD increases UCD competence.

2.2.4 Organizational Work Practices

Prior studies have observed that internal communications in an organization (Rosenbaum et al., 2000;

Venturi et al., 2006), management support (Gulliksen et al., 2004; Rosenbaum et al., 2000; Venturi et al.,

2006), and the involvement of cross-functional teams (Rosenbaum et al., 2000) are key success factors

for the UCD practice in organizations. For instance, examining the role of organizations in facilitating user

involvement, Iiavri (2006) observed that organizational culture influenced UCD practice. Hence, we

anticipate that organizational work will have a direct and positive impact on practices on the efficient and

effective use of data on users and context of use in UCD practices.

Hypothesis 4: The amount of organizational work practices committed to UCD increases efficiency

and effectiveness of using data on users and context of use

2.2.5 UCD Competence

Lastly, we also consider UCD practitioners’ competence. Prior studies have observed that the knowledge

and experience of UCD practitioners largely affect the outcome of usability evaluations (Hertzum &

Jacobsen, 2001) and affect the approach and implementation of the UCD practice as well (Gulliksen et al.,

2006). Suwa and Tversky (2001) observed the superiority of experienced designers over novices in

generating new ideas from external representations, such as sketches. However, merely having

competence is not enough; one needs to efficiently and effectively use the competence in a way that

generates value to the organization (Ritter & Gemünden, 2004). Highly competent and experienced

practitioners, besides better recognizing the need to bring value to the organization, are better equipped to

create such value. Experienced practitioners are more informed about the overall importance of

understanding users and their use contexts and the different possibilities that exist to do so. Moreover,

experienced practitioners are more aware of the need for financial and time resources to the UCD

practice. Hence, we anticipate that UCD competence will directly and positively affect efficient and

effectively use of data on users and their use contexts in UCD practices.

Hypothesis 5: UCD competence increases efficiency and effectiveness of using data on users and

their use context

Communications of the Association for Information Systems 321

Volume 40 Paper 14

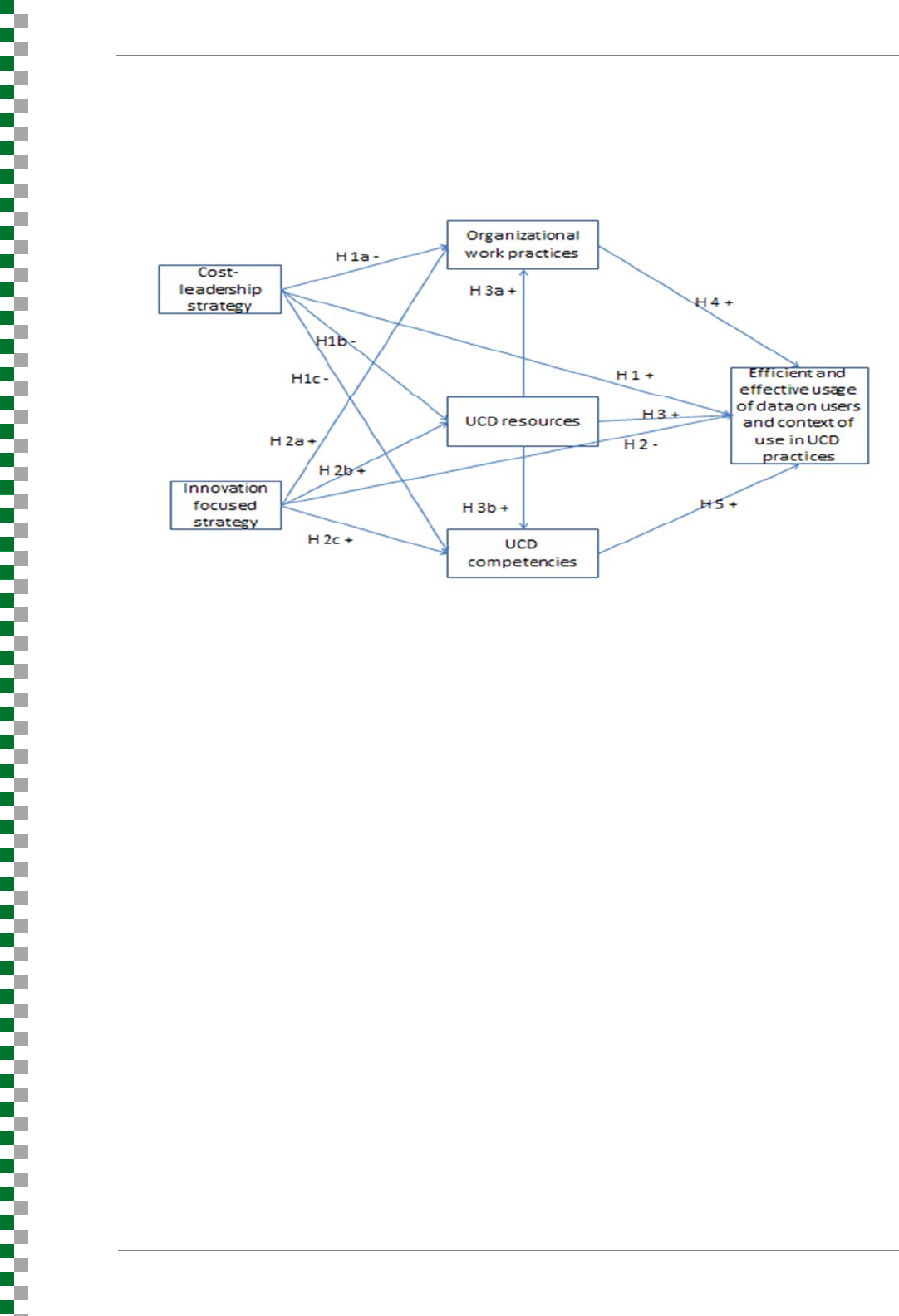

2.3 Research Model

Based on the hypotheses we formulate above, Figure 1 presents our research model. In Section 3, we

explain how we collected the data and tested the model.

Figure 1. The research model

3 Methodology

To test our research model, we conducted a survey and analyzed the data we obtained with the PLS-SEM

technique. Researchers commonly use surveys to test hypotheses (Johnson & Turner, 2003; Lazar, Feng,

& Hochheiser, 2010). SEM is especially useful to test models that include mediation and makes it possible

to test the structural and measurement parts of a model at the same time.

3.1 Sample

We collected data via an online questionnaire that we sent to UCD practitioners involved in designing and

developing mobile applications. We emphasized this focus in both the questionnaire invitation and in the

introduction to the questionnaire. Acknowledging the fact that the UCD practice occurs in a complex

organizational environment that involves multiple stakeholders with distinct backgrounds and worldviews

(Suchman, 2002), different expectations (Krippendorf, 2006), and different criteria for determining a

project’s success (Baxter & Sommerville, 2011), we were interested in responses from practitioners in the

following three project roles: 1) UCD specialists (e.g., UX designer, interaction designer, usability

engineer), who implement the UCD practice and make use of its gathered data; 2) project managers, who

are familiar with their organizations’ organizational strategy and have decision making power in allocating

UCD competence and UCD resources; and 3) software developers, who also use data gathered from the

UCD practice. Practitioners in these project roles are both on the management level (i.e., project

managers) and on operational level (i.e., UCD specialists and software developers). In small firms in

particular, operational-level practitioners are commonly also involved in making strategies and decisions.

As such, such individuals know about both UCD practice and organizational strategy. . In particular, those

involved in the UCD practice have numerous job titles and educational backgrounds. Thus, we collected

data based on non-probabilistic sampling—a valid and common practice (Lazar et al. 2010) in cases

where one cannot apply a strict random sampling.

We contacted potential respondents through multiple channels, such as emails and the mailing lists

professional communities (e.g. HCI, UXPA, IXDA). In addition, we posted a link to the questionnaire on

relevant and active discussion forums (e.g. LinkedIn groups, Google+ communities) and on Twitter using

322 The Role of Organizational Strategy in the User-centered Design of Mobile Applications

Volume 40 Paper 14

relevant hash (#) tags. The survey was available online for four continuous weeks during February and

March in 2013.

We received a total of 100 responses from 20 countries: most individuals came from Finland (46%), the

US (12%), Sweden (9%), Netherlands (5%), and Israel (5%). Most of the respondents worked as UX

designers (33%), project managers (19%), software developers (8%), and project owners (7%).

The respondents worked primarily in companies (as opposed to freelancers) of different sizes. About 28

percent of the companies had 10 or fewer employees, 24 percent had 11-50 employees, 7 percent had

51-100 employees, 18 percent had 101-1000 employees, and the remaining 23 percent had more than

1000 employees. The median company size was 46 employees and the mode was 5. In terms of business

sectors, software (36%) and usability/UX consulting (18%) were the two largest categories; other sectors

including education, telecommunications, design, technology research and gaming represented a single-

digit percentage. At face value, the respondents worked in environments in which one would expect them

to—small, medium-sized, and large enterprises mainly in the software business and usability/UX

consulting. Although we cannot claim representativeness, we assume that the respondents represent a

common sample for our population.

While other studies (e.g., Clemmensen, Hertzum, Yang, & Chen, 2013) have found differences between

usability specialists and software developers, we extensively tested difference between the three groups

(UCD specialists, project managers, and software developers) for the core constructs based on ANOVA

but could not find any significant differences. Therefore, we concluded that the sample was homogeneous

enough to conduct SEM.

3.2 Measures

We based the measures for the core concepts in this study on established items from existing studies

(see Table 1). Furthermore, we pilot tested the questionnaire following Dillman’s (2006) three-stage

recommendations. We grouped questions into four sections: 1) questions that address the use context in

mobile application design—the perceived importance of contextual aspects and the use, purpose, and

perceived effectiveness of methods to gather data on users and their use contexts; 2) questions related to

how methods and collected data in UCD practice are utilized and informing the design artefact; 3)

questions about organizational setting: business sector, size, organizational practices, strategy, and

competitive environment, and 4) questions about the participants themselves (i.e., demographic

questions): their geographical location, experience with UCD practice, and main role in mobile application

projects.

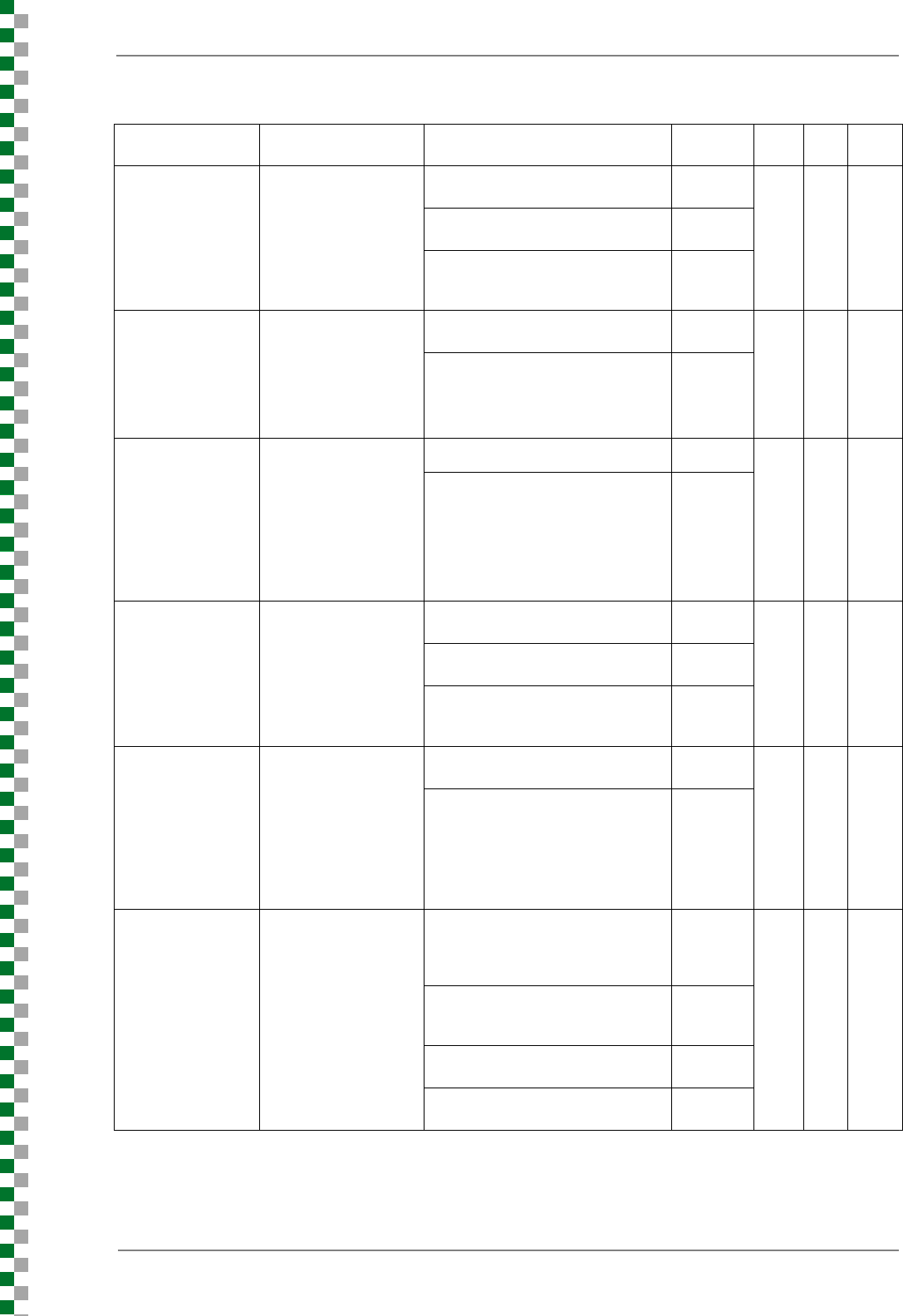

Confirmatory factor analysis using Warp PLS showed acceptable levels of convergent and discriminant

validity. Convergent validity was acceptable for all constructs. Factor loadings exceeded .70, and all

average variance extracted (AVE) values were above .60 (Fornell & Lacker, 1981). Construct reliability

was acceptable because composite reliability was above .80, which exceeds the .60 benchmark. Multi-

collinearity was not significant since the average of full collinearity VIF equaled 1.099, and full collinearity

VIF equaled 1.445—far below the 3.3 benchmark.

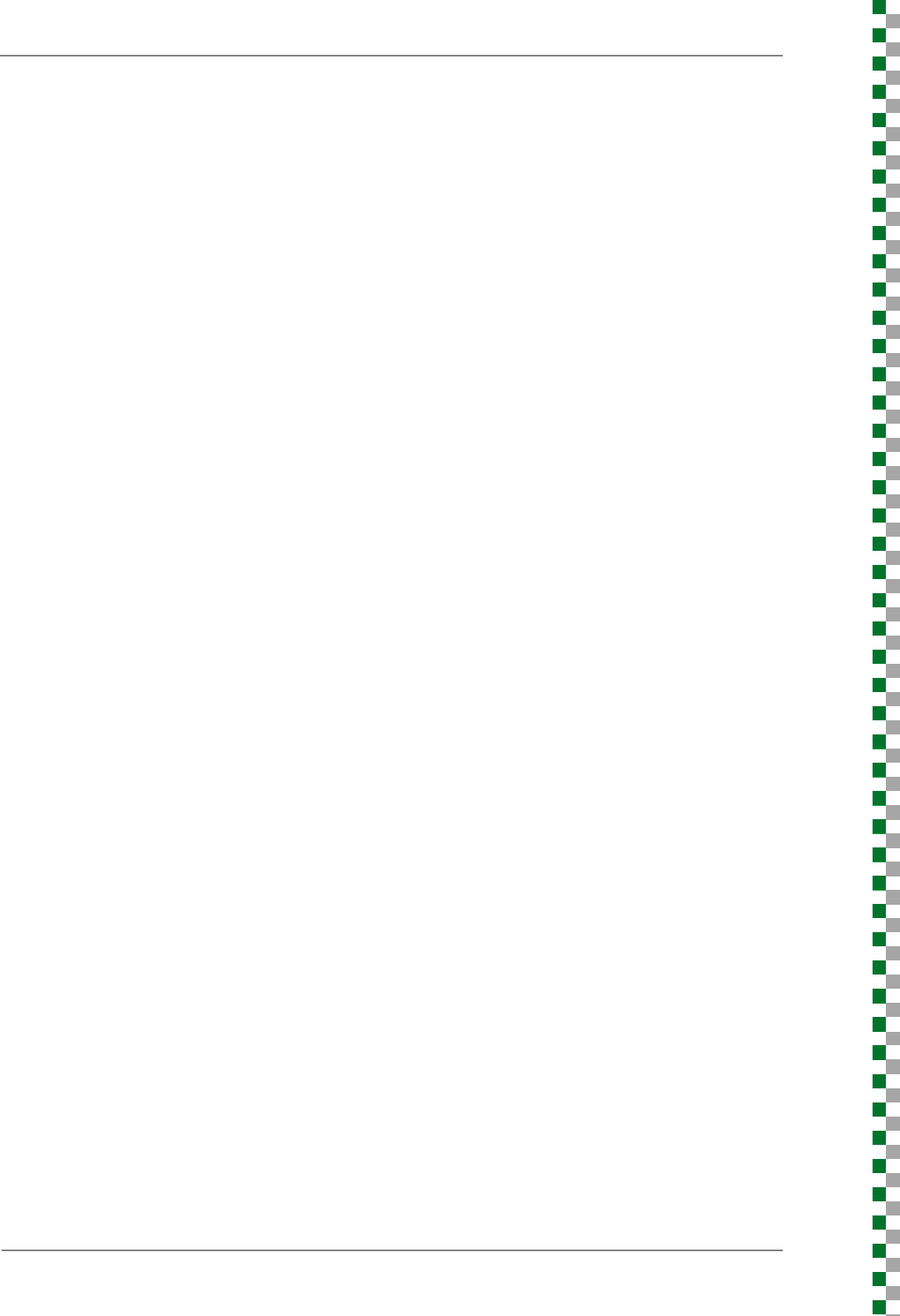

Discriminant validity was acceptable because the average squared correlation of any pair of constructs did

not exceed the average of the respective average variance extracted (see Table 2).

Communications of the Association for Information Systems 323

Volume 40 Paper 14

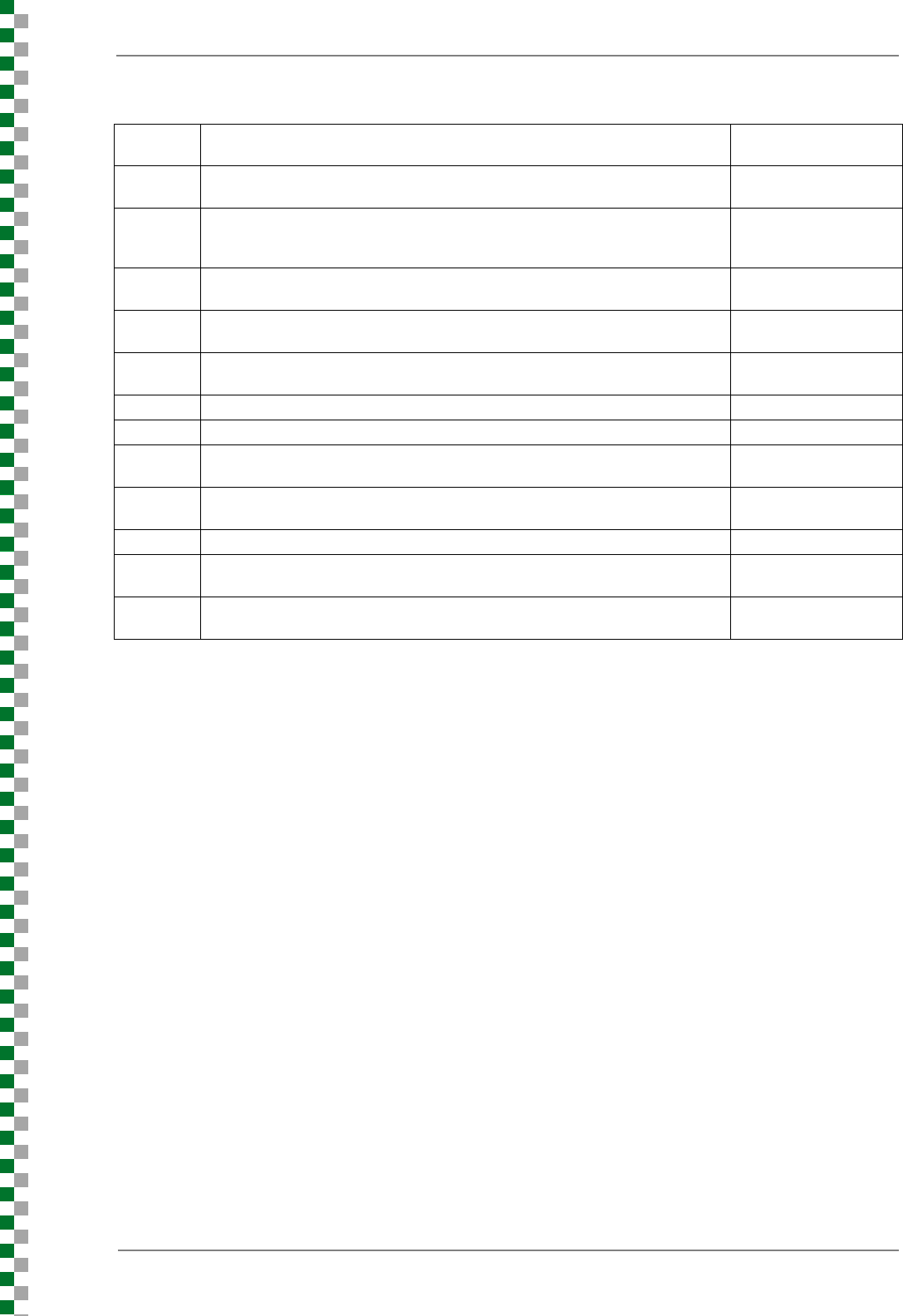

Table 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Construct Question heading Item

Std. factor

loading

AVE VIF

Comp.

rel.

Cost-leadership

strategy

(Treacy &

Wiersema, 1993)

Reflective scale

STRAT_COST

How important are the

following aspects to

your company’s

strategy?

(5-point: 1: not at all

important, 5: extremely

important)

Being cost leader with our

products/services

.83

.61 1.113 .82

Optimizing our operations to

minimize development costs

.71

Emphasizing economies of scale

and scope with our

products/services

.79

Innovation-focused

strategy

(Rönkkö & Peltonen,

2012)

Reflective scale

STRAT_INN

How important are the

following aspects to

your company’s

strategy?

(5-point: 1: not at all

important, 5: extremely

important)

Producing a continuous stream of

innovative products/services

.89

.78 1.544 .88

Being unique in our industry (e.g.,

with regard to product/service)

.89

UCD resources

(Monahan et al.,

2008)

DP_RESOU

How do the following

factors influence the

expected result from

the data gathering

methods you have

used?

(7-point: 1: not at all

influential, 7: extremely

influential)

Project budget .89

.79 1.198 .88

Project time constraints .89

Organizational work

practices

(Seyal, Awais,

Shamail, & Abbas,

2004)

Reflective scale

ORG_PRACT

How well do the

following statements

describe the work

practices at your

company?

(7-point: 1: strongly

disagree, 7: strongly

agree)

Employees are encouraged to

contribute to the team

.88

.75 1.895 .90

Employees are given regular

feedback on their performance

.81

Employees are encouraged to bring

new ideas to work practice

.91

UCD competence

(Monahan et al.,

2008)

DP_COMPET

How do the following

factors influence the

expected result from

the data gathering

methods you have

used?

(5-point: 1: not at all

influential, 2: extremely

influential)

Experience with methods from

previous projects

.84

.70 1.238 .83

Competence of available staff .84

Efficient and

effective use of data

on users and

context of use

Formative scale

EVAL_DATA

To what level do you

agree or disagree with

the following

statements. The data

we gather …

(7-point: 1: strongly

disagree, 7: strongly

agree)

Is efficiently used in my company

(efficiency = achieving the

maximum productivity with minimum

wasted effort)

.77

.61 1.684 .86

Is effectively used in my company

(effectiveness = being successful in

producing the desired result)

.86

Significantly improve our

understanding of contexts of use

.79

Is crucial to the success of our

mobile app

.70

324 The Role of Organizational Strategy in the User-centered Design of Mobile Applications

Volume 40 Paper 14

Table 2. Interconstruct Correlations and Square Root of AVE

STRAT_INN STRAT_COST ORG_PRACT DP_COMPET DP_RESOU EVAL_DATA

STRAT_INN

(0.886)

STRAT_COST

-0.023 (0.780)

ORG_PRACT

0.549 -0.239 (0.869)

DP_COMPET

0.125 0.042 0.006 (0.839)

DP_RESOU

-0.023 0.190 -0.134 0.337 (0.890)

EVAL_DATA

0.455 -0.135 0.546 0.281 0.100 (0.782)

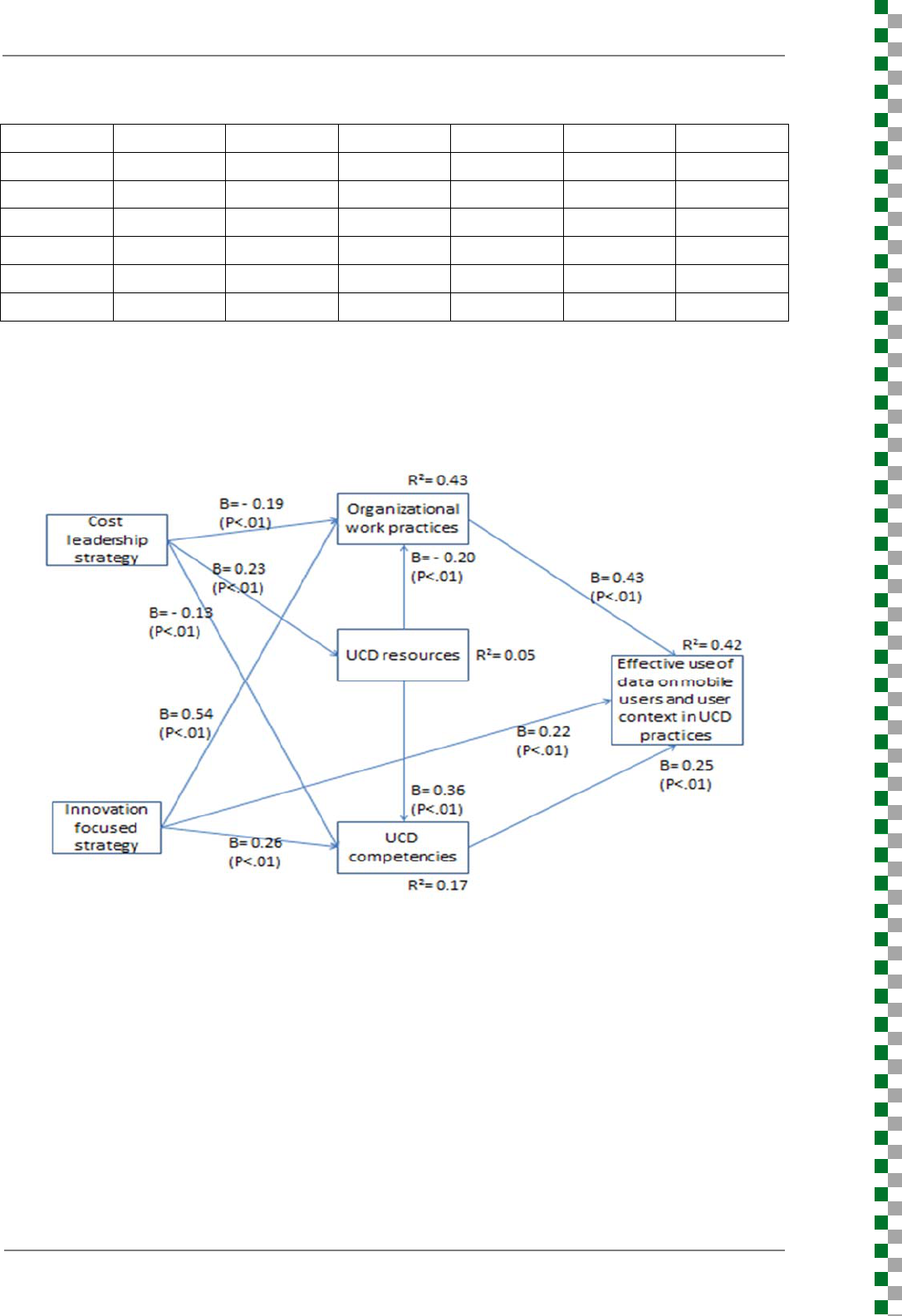

4 Results

We trimmed the original research model in Figure 1 by omitting insignificant paths. The final structural

regression model (see Figure 2) presented a good fit (Tenenhaus GOF equals .432). Overall, the

explained variance of the evaluation of data use was moderate (R

2

= .42).

Figure 2. Structural Regression Model

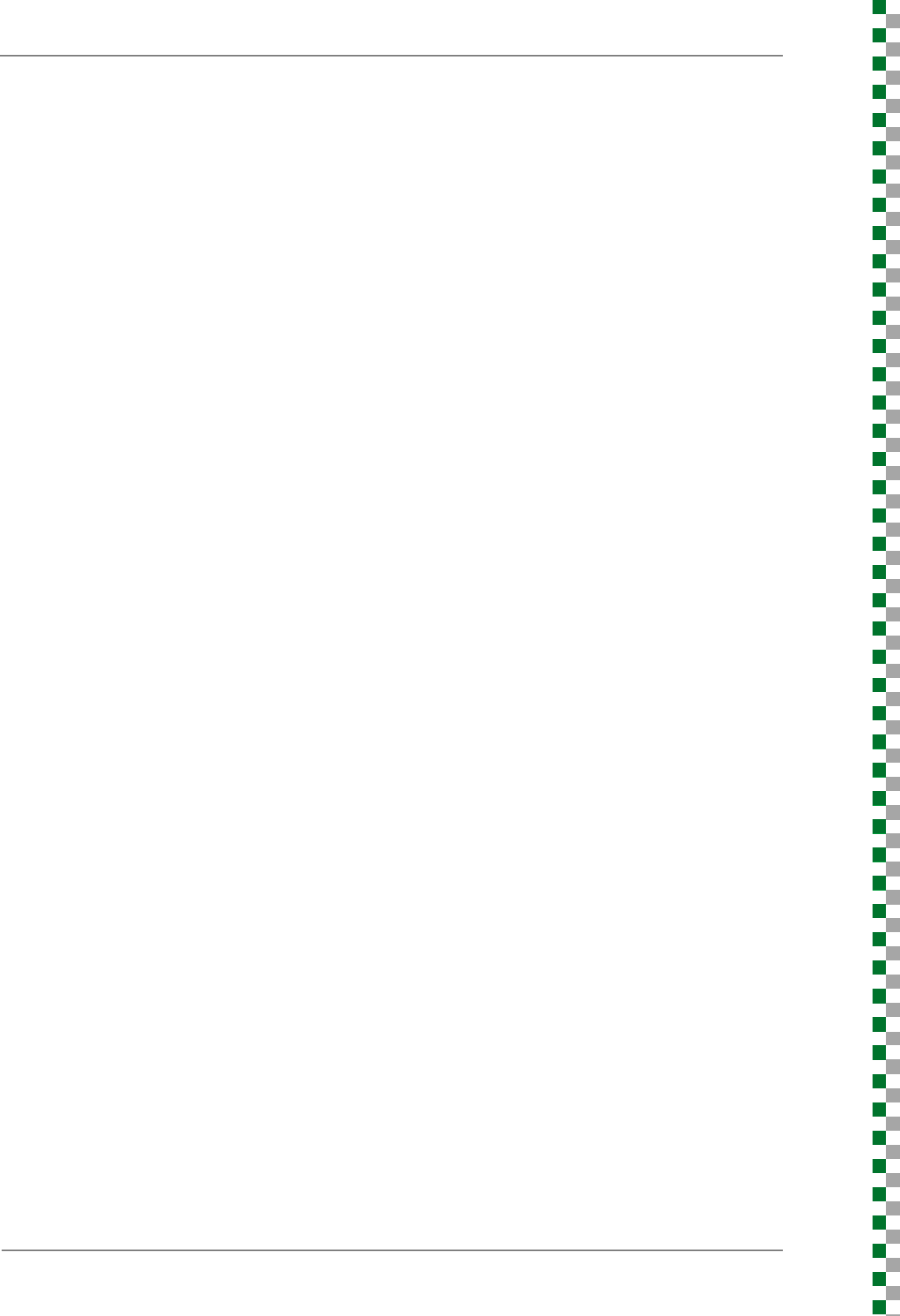

Table 3 overviews the hypotheses: we found support for seven and did not find support for four. Further,

two of the supported hypotheses showed a direction opposite to what we hypothesized. We will discuss

the results in more detail in Section 5.

Communications of the Association for Information Systems 325

Volume 40 Paper 14

Table 3. Overview of Accepted and Rejected Hypotheses

H1

Cost-leadership strategy increases efficiency and effectiveness of using data

on users and context of use.

Not supported

H1a

Cost-leadership strategy decreases organizational work practices committed to

UCD.

Supported

H1b

Cost-leadership strategy decreases resources committed to UCD. Supported in opposite

direction but weak

relation

H1c

Cost-leadership strategy decreases UCD competence Supported but weak

relation

H2

Innovation-focused strategy decreases efficiency and effectiveness of using

data on users and context of use.

Not supported

H2a

Innovation-focused strategy increases organizational work practices committed

to UCD

Supported

H2b Innovation-focused strategy increases resources committed to UCD Not supported

H2c Innovation-focused strategy increases UCD competence Supported

H3

The amount of resources committed to UCD increases efficiency and

effectiveness of using data on users and context of use.

Not supported

H3a

The amount of resources committed to UCD increases organizational work

practices committed to UCD.

Supported in opposite

direction

H3b The amount of resources committed to UCD increases UCD competence. Supported

H4

The amount of organizational work practices committed to UCD increases

efficiency and effectiveness of using data on users and context of use..

Supported

H5

UCD competence increases efficiency and effectiveness of using data on

users and their use context

Supported

5 Discussion

In this section, we discuss the results and the hypotheses in greater detail. First of all, it is interesting to

see that the model itself had a high predictive value and explained the efficiency and effectiveness of the

UCD practice related to data on users and use context to a significant extent. To our knowledge, this

model represents one of the first attempts to connect the broader stream of research on strategy and

innovation to UCD practice. Further, we introduce an explanatory rather than a qualitative or descriptive

model. However, the model remains limited in the sense that it is focused on the UCD practice, while, in

the end, the actual use of mobile applications is the decisive factor. In other words, we only tested the

UCD practice’s of efficient and effective use of data in UCD practices informing the design of mobile

applications, not their use. As such, we can claim only to contribute to how the UCD practice leads to

better informed designs, while taking conditions like strategy orientation and how design teams operate

within constraints of an organizational setting into account.

We found no main effect between a cost-leadership strategy and the efficiency and effectiveness data on

users and use context is used in the UCD practice of mobile applications (H1). Further, the availability of

UCD resources, organizational work practices, and UCD competence (H1a-c) mediated the effect.

Interestingly, only the relation with UCD resources was positive, contrary to our expectations (H1b), while

the other two relations were negative (H1a and H1c). This finding implies that cost-focused companies are

prepared to invest in but do not positively contribute to favorable organizational work practices and UCD

competence, which confirms traditional insights from the strategic management literature regarding cost-

focused strategies that have optimization at their core.

In contrast to cost-leadership strategy, we found a relation between an innovation-focus strategy and

efficiency and effectiveness in which data on users and use context are used in the UCD practice of

mobile applications (H2). Strikingly, we found no relation between an innovation-focused strategy and the

availability of UCD resources (H2b). Apparently, the respondents’ organizations thought it more important

to develop positive organizational work practices and UCD competence than providing their UCD

practitioners with the time and money for actual UCD activities (H2a and H2c). This finding confirms

insights from innovation management. Researchers have previously emphasized that organizations need

326 The Role of Organizational Strategy in the User-centered Design of Mobile Applications

Volume 40 Paper 14

to facilitate internal communication to support UCD practices (Rosenbaum et al. 2000; Venturi et al,

2006).

Although earlier studies emphasize the significant influence of budget and time-related constraints on the

UCD practice (e.g., Monahan et al., 2008; Rosenbaum et al., 2000; Vredenburg et al., 2002), this does not

affect the UCD practice with regard to the efficient and effective use of data on users and context

(hypothesis 3). Organizations rely mainly on practitioners’ UCD competence and organizational work

practices in designing mobile applications and don’t provide resources for supporting UCD practices.

However, we found a negative relation between UCD resources (time and budget) and organizational

work practices, which implies that, due to temporal and financial constraints, UCD practitioners rely on

open communication and collaboration (H3a but with a reversed direction). The impact of UCD resources

on UCD competence showed a moderate positive contribution (H3b).

We also found support for the hypothesis that organizational work practices (i.e., established work

practices that contribute to creativity, open collaboration, and the sharing of ideas in the work

environment) have a positive relationship with efficient and effective use of data on users and context of

use in design practices. Creation and sharing of ideas and knowledge within the organization, in order to

streamline the UCD practice proves to be highly relevant (hypothesis 4). This relation was the strongest.

The finding suggests that design teams that are open and sharing will more likely use all kinds of data

sources that are relevant to them in a more efficient and effective way in their design practices.

Our results show that UCD practitioners’ UCD competence essentially determines how effectively they

use data on users and their use contexts (H5) at least in the context of mobile application design. The

hypothesis supports the idea that competent practitioners are more likely to efficiently and effectively use

resources by finding alternative solutions to a design problems and capitalizing on earlier experiences.

However, we did not study practitioners’ actual qualifications and experience in designing and developing

mobile applications. As such, future research could more extensively operationalize these two concepts in

relation to practitioners’ UCD competence to better explain their role in the UCD practice.

Our study contributes to strategic management literature by showing how different high-level strategic

orientations affect the UCD practice on the operational level. Our tested hypotheses provide a basis for

theorizing how strategic decisions in organizations affect UCD practitioners’ day-to-day work practices.

Moreover, we contribute to IS literature by showing how both strategic orientation as and the availability of

resources and competence in organizations affects the UCD practice. Given the complex, multifaceted

nature of organizations and their operation, our study also contributes an interdisciplinary approach by

combining theories from strategic management, IS management, and the HCI disciplines.

On a practical level, our findings imply that practitioners, especially those in managerial positions, in

organizations that design and develop mobile applications should take steps to ensure that they have

practitioners with relevant skills and experience to produce better user-informed designs in a timely

manner. As we explain above, understanding users and their use contexts during the UCD practice in the

mobile apps era requires new competence. In the highly competitive mobile business market, obtaining

such competence may be part of the rare capabilities that give an organization a competitive advantage.

6 Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Research

In this paper, we show links between the organizational strategy and the way practitioners, particularly

UCD specialists such as UX and interaction designers, deal with data about users and their use contexts

when designing mobile applications. An innovation-focused strategy has a direct impact on the way

designers work (i.e., their work practices and individual UCD competence) and also how efficiently and

effectively they use data sources on users and their use contexts. However, when dealing with users’

dynamic contexts and needs, practitioners rely on their competence and experience from earlier projects

due mainly to project resource limitations.

This study is the first that relates organizational context and innovation strategies with UCD practices,

particularly with regard to the way in which practitioners use data on users and their use contexts. To our

knowledge, this study is also the first that tries to develop more explanatory models with regard to the

UCD practice in the HCI discipline. The connection between an outside-in strategy focus with an inside-

out perspective that focuses on UCD resources, UCD competence, and organizational work practices

proves to be fruitful. Our results show that the latter plays a clear mediating role between strategy

orientation and the efficient and effective use of data on users and context of use in UCD practices [

Communications of the Association for Information Systems 327

Volume 40 Paper 14

We started from strategic and innovation management literature, as well as from resource-based view to

address an important under-researched interdisciplinary domain (i.e., the connection between strategy

thinking and design practices, more specifically on the efficient and effective use of data on users and

context of use in designing mobile applications). Developing explanatory models, instead of descriptive

and more qualitative models, that take a strategy perspective as a starting point and pay attention to

moderating resources and capabilities in explaining a specific UCD practice may extend our knowledge on

the UCD practice and more generally on design practice.

With regard to further research, we need more research that focuses on what organizations expect from

the UCD practice, specifically if budgets and time, also for developing competencies, for UCD practices

are constrained. More research is also needed on the way information on users and their context exactly

plays a role in the UCD practice. Furthermore, organizations may not be able to efficiently use data due to

its quality, a lack of precision of the data, or even information overload. We see two distinct research

approaches. On the one hand, we need more research that adopts large-scale surveys to develop more

sound research models and a more detailed and precise operationalization of core concepts relating

organizational related characteristics, such as strategic orientation, resource management, and work and

(user-centric) design practices, as well as the relation between UCD practices and the use of data

sources. These research models should consider the actual use of mobile, or any other type of,

application. On the other hand, we need more detailed qualitative research into everyday design practice.

More extensive qualitative research and observational studies will provide deeper insights that quantitative

research can test further.

On a practical level, this paper highlights the importance of having an open innovative strategy (i.e., one

that encourages individuals in an organization to communicate and share ideas) to design better products.

Moreover, practitioners with relevant skills and experience in terms of understanding user needs and their

use contexts can be critical assets that give organizations a competitive advantage.

This study’s main limitations concern the data we collected and the model we tested. First, we collected

data based on a convenience sample (an issue common in researching those involved in the UCD

practice); we depended highly on practitioners’ willingness to participate. We put much effort in collecting

data by addressing respondents in several ways. To further research in this domain, one needs to involve

more UX and interaction designers, project managers, and software developers to better represent those

who design and develop usable and useful interactive (mobile) systems and garner richer insights that

may help improve their work and (user-centric) design practices.

As for our model’s limitations, we did not consider the socio-spatial context in which users used the

designed application (e.g., whether users used it for specific work-related activities in relatively stable and

predictable context or for non-work activities in more diverse and dynamic context). Including this factor in

future would allow one to more thoroughly analyze on the tendency of UCD practitioners to collect user

and context data and to analyze the interactions between organizational factors and use-context factors

and their influence on UCD practitioners. Moreover, future research needs to develop and test alternative

models. With this paper, we connect strategic and innovation management research to research into UCD

practice and, in doing so, open new interdisciplinary research venues.

Acknowledgments

We greatly thank the reviewers and the senior editor for their extremely useful and constructive comments

on earlier drafts of this paper. We also thank Balsamiq Studios and Rally Software for giving away a few

licenses of their software for the study. The research work for this study was funded by the Turku Centre

for Computer Science and by a grant from the Foundation for Economic Education in Finland

(Liikesivistysrahasto).

328 The Role of Organizational Strategy in the User-centered Design of Mobile Applications

Volume 40 Paper 14

References

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1),

99-120.

Baxter, G., & Sommerville, I. (2011). Socio-technical systems: From design methods to systems

engineering. Interacting with Computers, 23(1), 4-17.

Bergvall-Kåreborn, B., & Howcroft, D. (2011). Mobile applications development on Apple and Google

platforms. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 29, 565–580.

Boland, R. J., Jr. (1978). The process and product of system design. Management Science, 24(9), 887-

898.

Bygstad, B., Ghinea, G., & Brevik, E. (2008). Software development methods and usability: Perspectives

from a survey in the software industry in Norway. Interacting with Computers, 20(3), 375-385.

Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail.

Harvard Business Press.

Clemmensen, T., Hertzum, M., Yang, J., & Chen, Y. (2013). Do usability professionals think about user

experience in the same way as users and developers do? In P. Kotzé, G. Marsden, G. Lindgaard, J.

Wesson, & M. Winckler (Eds.), Human-computer interaction—INTERACT 2013 (pp. 461-478).

Berlin: Springer.

Cross, N. (2001). Designerly ways of knowing: Design discipline versus design science. Design Issues,

17(3), 49-55.

De Wit, B., & Meyer, R. (2010). Strategy synthesis: Resolving strategy paradoxes to create competitive

advantage (3

rd

ed.). Australia: Cengage Learning.

Dillman, D. A. (2006). Mail and Internet surveys: The tailored design method—2007 update with new

Internet, visual, and mixed-mode guide (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Dix, A., Rodden, T., Davies, N., Trevor, J., Friday, A., & Palfreyman, K. (2000). Exploiting space and

location as a design framework for interactive mobile systems. ACM Transactions on Computer-

Human Interaction, 7(3), 285-321.

Eshet, E. & H. Bouwman (2015). Addressing the context of use in mobile computing: A survey on the

state of the practice. Interacting with Computers. Volume 27 (4): 392-412. doi: 10.1093/iwc/iwu002

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables

and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

Gould, J. D., & Lewis, C. (1985). Designing for usability: Key principles and what designers think.

Commununications of the ACM, 28(3), 300-311.

Gulliksen, J., Boivie, I., & Göransson, B. (2006). Usability professionals—current practices and future

development. Interacting with Computers, 18(4), 568–600.

Gulliksen, J., Boivie, I., Persson, J., Hektor, A., & Herulf, L. (2004). Making a difference—a survey of the

usability profession in Sweden. In Proceedings of the 3rd Nordic Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction (pp. 207-215). ACM Press.

Hassenzahl, M., & Tractinsky, N. (2006). User experience—a research agenda. Behaviour & Information

Technology, 25(2), 91-97.

Henfridsson, O., & Lindgren, R. (2005). Multi-contextuality in ubiquitous computing: Investigating the car

case through action research. Information and Organization, 15(2), 95-124.

Hertzum, M., & Jacobsen, N. E. (2001). The evaluator effect: A chilling fact about usability evaluation

methods. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 13(4), 421–443.

Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., & Ram, S. (2004). Design science in information systems research.

MIS Quarterly, 28(1), 75-105.

Iivari, N. (2006). “Representing the User” in software development—a cultural analysis of usability work in

the product development context. Interacting with Computers, 18(4), 635-664.

Communications of the Association for Information Systems 329

Volume 40 Paper 14

ISO. (2010). ISO 9241-210:2010 Ergonomics of human-system interaction-Part 210: Human-centred

design for interactive systems. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization.

Johnson, B., & Turner, L. A. (2003). Data collection strategies in mixed methods research. In A.

Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp.

297-319).

Johnson, P. (1998). Usability and mobility: Interactions on the move. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop

on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices.

Krippendorff, K. (2006). The semantic turn: A new foundation for design. Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis.

Lazar, J., Feng, J. H., & Hochheiser, H. (2010). Research methods in human-computer interaction. New

York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Mata, F. J., Fuerst, W. L., & Barney, J. B. (1995). Information technology and sustained competitive

advantage: A resource-based analysis. MIS Quarterly, 19(4), 487-505.

Mayhew, D. J. (1999). The usability engineering lifecycle: A practitioner’s handbook for user interface

design. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Mintzberg, H. (1987). The strategy concept I: Five Ps for strategy. California Management Review, 30(1),

11-24.

Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B., & Lampel, J. (2009). Strategy safari: The complete guide through the wilds of

strategic management. London: Prentice Hall.

Monahan, K., Lahteenmaki, M., McDonald, S., & Cockton, G. (2008). An investigation into the use of field

methods in the design and evaluation of interactive systems. In Proceedings of the 22nd British HCI

Group Annual Conference on People and Computers: Culture, Creativity, Interaction (vol. 1, pp. 99-

108). Swinton, UK: British Computer Society.

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M. A., & Chatterjee, S. (2007). A design science research

methodology for information systems research. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(3),

45-77.

Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. New York,

NY: Simon and Schuster.

Ritter, T., & Gemünden, H. G. (2004). The impact of a company’s business strategy on its technological

competence, network competence and innovation success. Journal of Business Research, 57(5),

548–556.

Robey, D., & Markus, M. L. (1984). Rituals in information system design. MIS Quarterly, 8(1), 5-15.

Rönkkö, M., & Peltonen, J. (2012). Software industry survey. Software Business Lab. Retrieved from

http://www.softwareindustrysurvey.org/

Rosenbaum, S., Rohn, J. A., & Humburg, J. (2000). A toolkit for strategic usability. In Proceedings of the

SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 337-344). ACM Press.

Schaffer, E. (2004). Institutionalization of usability: A step-by-step guide. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Schmidt, R., Lyytinen, K., & Keil, P. C. M. (2001). Identifying software project risks: An international Delphi

study. Journal of Management Information Systems,

17(4), 5-36.

Seffah, A., Desmarais, M. C., & Metzker, E. (2005). HCI, usability and software engineering integration:

Present and future. In A. Seffah, J. Gulliksen, & M. C. Desmarais (Eds.), Human-centered software

engineering—integrating usability in the software development lifecycle (pp. 37-57). Berlin:

Springer.

Sein, M., Henfridsson, O., Purao, S., Rossi, M., & Lindgren, R. (2011). Action design research. MIS

Quarterly, 35(1), 37-56.

Seyal, A. H., Awais, M. M., Shamail, S., & Abbas, A. (2004). Determinants of electronic commerce in

Pakistan: Preliminary evidence from small and medium enterprises. Electronic Markets, 14(4), 372-

387.

330 The Role of Organizational Strategy in the User-centered Design of Mobile Applications

Volume 40 Paper 14

Sharp, H., Rogers, Y., & Preece, J. (2007). Interaction design: Beyond human-computer interaction (2nd

edition). New York: Wiley.

Suchman, L. (2002). Located accountabilities in technology production. Scandinavian Journal of

Information Systems, 14(2), 91-105.

Suwa, M., & Tversky, B. (2001). Constructive perception in design. In J. Gero & M. L. Maher (Eds.),

Computational and cognitive models of creative design V (pp. 227-239). University of Sydney,

Australia: Key Centre of Design Computing and Cognition.

Tidd, J., Bessant, J., & Pavitt, K. (2005). Managing innovation: Integrating technological, market and

organizational change. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Treacy, M., & Wiersema, F. (1993). Customer intimacy and other value disciplines. Harvard Business

Review, 71(1), 84-93.

Venturi, G., Troost, J., & Jokela, T. (2006). People, Organizations, and Processes: An Inquiry into the

Adoption of User-Centered Design in Industry. International Journal of Human-Computer

Interaction, 21(2), 219-238.

Vredenburg, K., Mao, J.-Y., Smith, P. W., & Carey, T. (2002). A survey of user-centered design practice.

In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 471-478).

New York, NY: ACM.

Wade, M., & Hulland, J. (2004). The resource-based view and information systems research: Review,

extension, and suggestions for future research. MIS Quarterly, 28(1), 107-142.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171-180.

Communications of the Association for Information Systems 331

Volume 40 Paper 14

About the Authors

Eyal Eshet is a post-doctoral researcher at IAMSR, Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland. He has

several years of work experience in software programming and design in industrial context, which shaped

his scope of research interest on the design practice.

Mark de Reuver is Assistant Professor at ICT Section, Faculty of Technology Policy and Management

Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands. He received his PhD degree in 2009 from Delft

University of Technology. Mark has published more than 65 journal and conference articles in the area of

mobile service innovation, platform governance, mobile service business model and smart living.

Harry Bouwman is a Finnish Distinguished Professor at IAMSR, Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland,

and an associate professor at ICT Section, Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, Delft

University of Technology, The Netherlands. His research is focused on ICT and organizations; ICT

Management; strategy, business models, and enterprise architecture; and mobile cloud computing and

mobile services.

Copyright © 2017 by the Association for Information Systems. Permission to make digital or hard copies of

all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not

made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and full citation on

the first page. Copyright for components of this work owned by others than the Association for Information

Systems must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on

servers, or to redistribute to lists requires prior specific permission and/or fee. Request permission to

publish from: AIS Administrative Office, P.O. Box 2712 Atlanta, GA, 30301-2712 Attn: Reprints or via e-

mail from [email protected].