BYU Studies Quarterly BYU Studies Quarterly

Volume 46 Issue 2 Article 2

4-1-2007

A History of Mormon Cinema A History of Mormon Cinema

Randy Astle

Gideon O. Burton

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq

Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Astle, Randy and Burton, Gideon O. (2007) "A History of Mormon Cinema,"

BYU Studies Quarterly

: Vol. 46 :

Iss. 2 , Article 2.

Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol46/iss2/2

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been

accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more

information, please contact [email protected].

Salt Lake City’s rst and only “Brigham Young Day,” August , , celebrating the premiere

of Twentieth Century Fox’s Brigham Young. Dean Jagger, who proved a remarkable likeness to

Brigham Young, waves to a crowd of Latter-day Saints, who were enthusiastic that their second

prophet and the LDS faith were being depicted seriously in a nationally prominent motion picture.

Perry Special Collections, BYU.

1

Astle and Burton: A History of Mormon Cinema

Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2007

BYU Studies 6, no. 2 (27) 13

A History of Mormon Cinema

Randy Astle with Gideon O. Burton

O

n March , , Richard Dutcher’s lm God’s Army was released

in Utah-area theaters. It was a seemingly new entity: a feature lm

created by a Latter-day Saint, about Mormon life (missionary work), and

marketed primarily toward LDS audiences. At the time, the website of

Dutcher’s company, Zion Films, paraphrased a prophecy of Spencer W.

Kimball, famous among LDS lmmakers, of a future day “when our lms,

charged with the faith, heartbeats, and courage of our people would play

in every movie center and cover every part of the globe. . . . A day when

Mormon lmmakers, with the inspiration of heaven, would produce mas-

terpieces which will live forever.”

e website then condently armed,

“at day has come.” It described God’s Army as “the rst of many unique

and enduring Mormon lms,” stating that “such an endeavor has not

been attempted before” and “aer seeing this lm, you will ask yourself,

‘Why hasn’t anyone done this before?’”

With the commercial success of

God’s Army, the notion that it was indeed the “rst Mormon lm”—with

Dutcher himself “the father of Mormon cinema”—generally caught hold

with critics, the public, and even Dutcher’s competitors.

Even though Dutcher’s contributions were notably signicant, Mor-

mon movies actually began a century earlier, soon aer the beginning

of lm itself, and successive generations have reinvented, redened, and

repeatedly heralded the advent of Mormon lm. Sixty years before God’s

Army, Twentieth Century Fox premiered Brigham Young in Salt Lake City.

On that day, Friday, August , , shops, schools, and businesses closed;

both Governor Henry Blood and Mayor Ab Jenkins declared it a holiday

(“Brigham Young Day”); and the city’s population swelled from , to

,, with , people packing the streets to glimpse a gala parade

2

BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 46, Iss. 2 [2007], Art. 2

https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol46/iss2/2

14 v BYU Studies

of the studio’s stars.

ere were shop window competitions and special

supplements in both the Salt Lake Tribune and Deseret News. President

Heber J. Grant held a banquet in the Lion House to honor the city’s distin-

guished guests, and that night, e Centre cinema—the city’s largest—sold

out at a pricey . per ticket, and thus six more theaters, totaling nearly

, seats, were lled for a simultaneous showing, making this world

premiere the largest in Hollywood history to that point. e crowds, seen

in newsreel footage, easily surpass those of any modern general confer-

ence or Sundance Film Festival, rivaling the foot trac of the Winter

Olympics. With President Grant’s public benediction on the lm—given a

few days earlier—fresh in their minds, surely the ecstatic Latter-day Saints

present would have thought themselves justied in declaring that Mormon

cinema had arrived.

Indeed, the cries of “Mormon cinema is born!” in echoed similar

proclamations from , , , and on back to .

In February of that

year, e Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints produced One Hundred

Years of Mormonism

in response to a spate of sensational Mormon-themed

lms that had been showing successfully in Europe and America.

A full een years later, in , when the Church announced the

production of its second historical lm (and the rst with an original

An empty soundstage at the LDS Motion Picture Studio. In its half century of

existence, the MPS has produced over one thousand lms. Courtesy Brigham

Young University.

3

Astle and Burton: A History of Mormon Cinema

Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2007

V 15A History of Mormon Cinema

musical score), All Faces West, it prompted the Detroit Michigan Free Press

to write, “At last the story of the Mormons is to be lmed!”

A month later

the Cleveland Ohio News conrmed that “the rst Mormon picture is

nished.”

Both newspapers were ignorant of previous Church-produced

and independent theatrical lms that had been alternately celebrating or

exploiting the Mormon story for years.

Movies and Mormonism took to each other quickly, but this is hardly

known in the absence of any comprehensive history of Mormon lm.

While I am not able to give an exhaustive history here, it is my intention to

give a more complete and coherent account than has previously been avail-

able in any single source; to bring to light largely unrecognized lms, lm-

makers, and movements (some artistically superior to their better-known

counterparts); and to provide an accurate contextual framework for the

production and reception of Mormon lms, past and present.

I oer this history as a starting point from which future critics,

lmmakers, and spectators may build. e necessary brevity of this his-

tory may open the way for more detailed discussions on specic lms,

people, eras, and movements. e ve historical periods or “waves” that I

have used to structure this history, while not denitive, are intended as a

framework within which past, contemporary, and even future lms may

be examined.

D S

Since God’s Army, “LDS cinema” or “Mormon cinema” has been the

label given to commercial feature lms that are marketed primarily to a

Latter-day Saint audience and that include an LDS director and Mormon-

themed subject matter. Such a narrow denition, however, proves inad-

equate for evaluating the full spectrum and impact of lms relating to

Mormonism and would exclude lms as diverse and important as Twentieth

Century Fox’s Brigham Young (), HBO’s Angels in America (), or

any of the hundreds of inuential institutional Church lms that have been

produced, whether Man’s Search for Happiness (), Johnny Lingo (),

or Legacy (). In this history, as is conventional in academic studies, I

have used “Latter-day Saint” or “LDS” to refer specically to the Church or

its members, while reserving “Mormon” to refer more broadly to the culture;

hence the preference for the term “Mormon cinema,” even though most

Latter-day Saints refer to the movement as “LDS cinema.”

My purpose is to survey the historical relationship between movies

and Mormonism generally, including the people, events, and cultural

4

BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 46, Iss. 2 [2007], Art. 2

https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol46/iss2/2

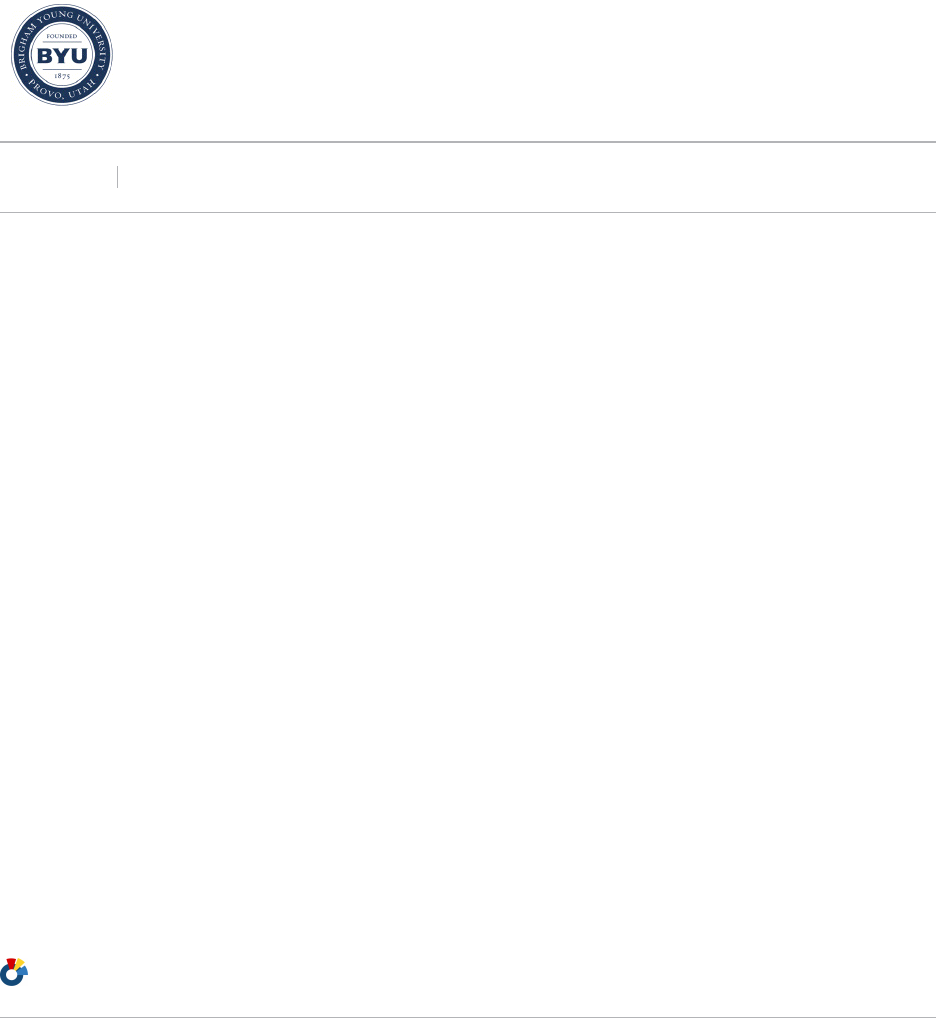

A rather precarious crane shot during the production of the Church’s remake

of Man’s Search for Happiness (). Institutional LDS lms are a prominent

component of Mormon cinema, epitomizing Mormon movies for many. LDS

Church Archives, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

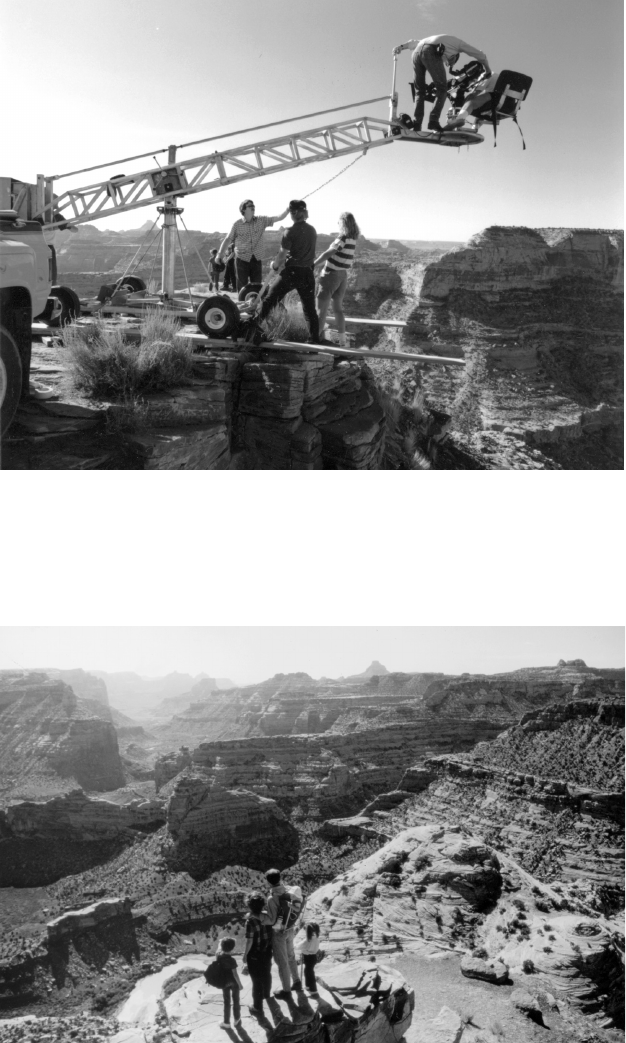

e scene resulting from the above crane shot for Man’s Search for Happiness. South-

ern Utah and Arizona deserts have been repeatedly used in lmmaking because of

their dramatic vistas. LDS Church Archives, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

5

Astle and Burton: A History of Mormon Cinema

Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2007

V 17A History of Mormon Cinema

forces both within the LDS faith and without that have shaped the evolu-

tion of Mormon lmmaking; the role of lm in Mormon life; and the way

Latter-day Saints have been depicted on lm by others. ese histories are

intertwined: mainstream Mormon-themed lms made outside of (and

oen in opposition to) the faith provoked institutional lmmaking; in

turn, the production and widespread use of lms by the Church and its

various institutions over the last century vindicated the medium and

trained and encouraged Latter-day Saints to develop the lm arts in new

and independent ways. Some LDS lmmakers, Dutcher in particular,

have reacted against institutional lms, creating movies that eschew the

idealistic characterizations and storylines so common in Church produc-

tions. Even those Latter-day Saints who never deal with Mormon sub-

jects but who have participated in the entertainment industry as actors,

technicians, and creative personnel t into the story, since Mormon lm

productions (institutional or private) have relied upon the talents of those

experienced in the mainstream industry. e emergence and increasing

robustness of Mormon cinema is in fact due to all of these factors, and not

just to the recent eorts of a few individuals or lms, however noteworthy

they have been.

Below I outline the ve periods or “waves” of Mormon cinema that

make up its history. Running through all of these periods are four distinct

subcurrents that help to further organize the chronological discussion.

Each is more or less prominent in a given period, but all occur in each of the

ve waves and together they constitute the larger eld of Mormon cinema:

. Depictions of Mormons in Mainstream Films

. Institutional (Church) Films

. Independent Mormon Films

. Latter-day Saints Working in the Mainstream Industry

Mormon literary scholars have taken a similar approach to these

four categories in their construction of the comprehensive Mormon Lit-

erature & Creative Arts database,

which in addition to literary works by

and about Mormons includes titles by non-Mormons important for their

depiction of Latter-day Saints (like the Sherlock Holmes novel A Study in

Scarlet—later adapted to lm) and mainstream work with no discernible

Mormon content authored by Latter-day Saints (such as Anne Perry’s Vic-

torian detective novels). It is my hope that a broad survey—including all

aspects of cinema as a social phenomenon—will help create connections

and continuity for the reader and expand the concept of what we can right-

fully consider the domain of Mormon cinema.

6

BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 46, Iss. 2 [2007], Art. 2

https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol46/iss2/2

18 v BYU Studies

F W M C

e history of Mormon lm divides naturally into ve distinct chron-

ological periods beginning in and averaging twenty-four years each,

with God’s Army marking the beginning of the h.

Similar constructs

in the history of Mormon literature and some national cinemas name such

periods “generations,” but here I use the term “waves” for two reasons.

First, the brevity of the periods has allowed many individuals to work in

multiple eras, something not implied in a generational label. Second, a

“new wave”—a popular term in lm history—indicates not just a personnel

or chronological dierence but a fundamental artistic dierence between

the new and the old it is replacing. e most famous cinematic new waves

all materialized as conscious reactions against preceding norms, using

innovative stylistic techniques to emphasize their independence. Eventu-

ally these new modes are absorbed into mainstream practice, making way

for another wave to replace them.

Despite the danger of oversimplication inherent in such a straight-

forward model, I feel that introducing such a construct into the history of

Mormon lm can be immensely useful. It provides a convenient short-

hand, for instance, allowing for labels such as “a Fih Wave lm,” but,

more importantly, it reveals historical patterns present in each period. By

looking at the waves that have preceded it, we can expect the Fih Wave,

which since has entered something of a production slump, to gradu-

ally expand until a critical mass is reached and something new emerges,

resulting in the advent of a Sixth Wave in the s. Other critics are cer-

tainly encouraged to amend, challenge, or replace the ve-wave structure,

but it is my hope that from this point forward at least some model will be

in place to contextualize discussions of Mormon lm.

e First Wave (1905–1929):

e Clawson Brothers and the New Frontier

is period coincides roughly with cinema’s silent era (before the

introduction of synchronous soundtracks). Films in this period divide

fairly distinctly between sensationalist pictures aimed at exploiting Mor-

monism’s peculiar history and somewhat propagandistic lms made in

response to these by e Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and

those sympathetic to it. Both types of pictures were shot on mm black-

and-white lm and were generally released to a paying public in commer-

cial cinemas.

7

Astle and Burton: A History of Mormon Cinema

Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2007

V 19A History of Mormon Cinema

e Second Wave (1929–1953): Home Cinema

is period has sometimes been considered a hiatus in LDS lmmak-

ing, though this is increasingly apparent as a misinterpretation. Pioneering

work in lmstrips, radio, and hitherto unheralded motion pictures was

laying the groundwork for all future institutional lmmaking. Depictions

from outside the Church were fewer but kinder in their representations.

On a technical level, both sound and cheaper mm lm stock were intro-

duced, with the occasional use of color. During this period the Church

nurtured a tremendous private lm distribution network that sidestepped

commercial theaters, not only allowing lmmakers to make works that

otherwise would not have existed, but creating a culture of cinematic

awareness among Latter-day Saints.

e ird Wave (1953–1974): Judge Whitaker and the Classical Era

e newly created BYU Motion Picture Studio started the production

of hundreds of Church lms, generally on mm lm stock, distributed

privately throughout the Church for multiple purposes and audiences.

Additional independent Mormon lms were attempted, and depictions

of Mormons in mainstream lms returned to showing them as objects of

curiosity as Hollywood standards relaxed.

e Fourth Wave (1974–2000): e Mass Media Era

e advent of video reduced costs and provided additional distribution

outlets, allowing many more Latter-day Saints to complete productions

within the marketplace and causing the total quantity of independent

works to increase dramatically. e Church also enlarged the scope of

its work by creating other production entities beyond BYU, oen shooting

on mm or even mm stock, and distributing its work through a variety

of channels including satellite broadcasts, television, VHS cassettes, and

destination cinemas at Church-owned visitors’ centers. Depictions of

Mormons in mainstream lm once again returned to sensationalist repre-

sentations, while large numbers of Latter-day Saints were working in the

entertainment industry.

e Fih Wave (2000–present): Cultural and Commercial Viability

Independent Mormon productions released on mm lm in com-

mercial theaters to a paying public have established a niche market within

American Mormonism. Video and DVD distribution of institutional and

independent Mormon lm are expanding, while Internet and digital lm

8

BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 46, Iss. 2 [2007], Art. 2

https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol46/iss2/2

20 v BYU Studies

suggest new formats and modes of distribution. An LDS Film Festival

now coincides annually with the Sundance Film Festival. Institutional,

independent, and mainstream treatments of Mormon themes, while still

distinct, have begun treating Mormonism with more complexity. Latter-

day Saints are starting to sense the emergence and importance of their

own lm tradition, suggesting the beginning of a culturally identiable

(but institutionally independent) Mormon cinema.

T H S

e advent of movies in the s coincided with important cultural

changes within e Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that

indicated a shi from pioneer isolation to twentieth-century integration.

e Manifesto ending polygamy came in , and the Salt Lake Temple

was dedicated in , ending forty years of construction and concretely

symbolizing the end of the pioneer period. e temple’s interior murals

were completed by artists who had been sent, as missionaries, to the Aca-

démie Julian in Paris where they became trained in modern styles such

as Impressionism and Expressionism. e murals thus had much more

in common with the French avant-garde than with the stark images of

previous Mormon painters. Additionally, the Church dissolved the local

People’s Party, encouraging members to aliate with national political

parties; it also closed down most of its private academies to accommodate

the previously distrusted public schools and sold o most of its businesses.

Such conciliatory eorts were rewarded when Utah gained its long-awaited

statehood on January , . Similarly, by the s Church leaders cau-

tiously ceased admonishing converts to move to Utah, essentially marking

the end of the gathering period. In short, the focus of the Church began to

shi from inward isolation to outward accommodation. e Church was

now ready to engage the world.

It is particularly tting that the Church’s rst recorded brush with

lm came in , in a situation consciously designed to demonstrate

Latter-day Saints’ similarity to other Americans. e Spanish-American

War was America’s rst conict aer Utah’s admission to the union, and

the majority of LDS Utahns viewed it as an opportunity to display their

patriotism. Hence, when Colonel Jay L. Torrey secured legislation to form

three companies of elite cavalry—the Rough Riders—Utahns reacted with

enthusiasm, with many enlisting in Torrey’s own regiment, known as the

Rocky Mountain Riders. John Q. Cannon—son of George Q. Cannon, First

Counselor in the First Presidency—became captain of the Utah Company,

9

Astle and Burton: A History of Mormon Cinema

Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2007

V 21A History of Mormon Cinema

which consisted of eighty-six men, mostly LDS. e group was mustered

into service on May , , at Fort Russell, Wyoming, and traveled by

rail to Jacksonville, Florida, where they remained throughout the sum-

mer. us they missed the famous charge up San Juan Hill but were on

hand in July to be lmed by the American Mutoscope Company. Among

many other titles lmed of the troops is one entitled Salt Lake City Com-

pany of Rocky Mountain Riders, a lengthy -foot piece (approximately

two and a half minutes) probably released immediately. While the Utah

Company was disappointed not to engage the Spanish, Cannon and his

men apparently did become the rst Latter-day Saints—or Utahns, for that

matter—to be lmed.

Less is known about when Latter-day Saints, in Utah or elsewhere, rst

viewed moving pictures. Early on, “editorials in Utah as elsewhere echoed

the concern, particularly of churchmen, that the unparalleled impact of the

moving picture image would harmfully inuence susceptible minds.”

It

would not be long, however, before exhibition venues proliferated in the

state, and by the close of cinema’s rst decade Mormon communities such

as Salt Lake City reportedly had exhibition facilities comparable to any city

in the nation. e Mormons were ready for the movies.

10

BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 46, Iss. 2 [2007], Art. 2

https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol46/iss2/2