BY ORDER OF THE

SECRETARY OF THE AIR FORCE

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE

PAMPHLET 63-123

14 APRIL 2022

Acquisition

PRODUCT SUPPORT BUSINESS CASE

ANALYSIS

ACCESSIBILITY: This publication is available on the e-Publishing website at www.e-

publishing.af.mil for downloading or ordering.

RELEASABILITY: There are no releasability restrictions on this publication.

OPR: SAF/AQD Certified by: SAF/AQD

(Ms. Angie Tymofichuk)

Supersedes: AFPAM 63-123, 1 June 2017 Pages: 124

This Department of the Air Force Pamphlet (DAFPAM) complements Air Force Instruction (AFI)

63-101/20-101, Integrated Life Cycle Management. It provides informational guidance and

recommended procedures for executing a Product Support Business Case Analysis (PS-BCA).

Additional non-mandatory guidance on best practices, lessons learned, and expectations are

available in the Department of Defense Product Support BCA Guidebook. To ensure

standardization, any United States Space Force (USSF) or United States Space Force (USAF)

organization supplementing this publication will send the implementing publication to the

Assistant Secretary of the Air Force/Product Support and Logistics (SAF/AQD) for review and

coordination before publishing. This publication applies to the Regular Air Force, the Air Force

Reserve, the Air National Guard, and, unless and until such time as independent guidance is issued,

the United States Space Force. It also applies to other individuals or organizations as required by

binding agreement or obligation with the Department of the Air Force (DAF). Note: Until such

time as the USSF issues its own guidance, all references to United States Air Force (USAF)

terminology, units, and positions will also apply to the equivalent in the USSF, as appropriate. For

example, references to Airmen will also apply to Guardians. References to MAJCOMs or NAFs

will also apply to Field Commands. References to wings will also apply to deltas/garrisons. Air

Staff roles and responsibilities (i.e. AF/A4) may also apply to the equivalent Office of the Chief

of Space Operations (Space Staff) office (i.e. SF/COO, etc), as appropriate. For nuclear systems

or related components ensure the appropriate nuclear regulations are applied as specified in AFI

63-101/20-101. Refer recommended changes and questions about this publication to the OPR

listed above using Air Force (AF) Form 847, Recommendation for Change of Publication; route

AF Forms 847 from the field through the appropriate chain of command. Ensure that all records

created as a result of processes prescribed in this publication are maintained in accordance with

2 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

AFI 33-322, Records Management and Information Governance Program, and disposed of in

accordance with the Air Force Records Disposition Schedule (RDS) in the Air Force Records

Information Management System (AFRIMS). The use of the name or mark of any specific

manufacturer, commercial product, commodity, or service in this publication does not imply

endorsement by the Air Force.

SUMMARY OF CHANGES

This document has been substantially revised and should be completely reviewed. It reflects

process improvements, evolving best practices, organizational structure changes, and

administrative updates.

Chapter 1—OVERVIEW 7

1.1. Product Support Business Case Analysis (PS-BCA) Pamphlet Overview. ............. 7

1.2. Business Case Analysis (BCA). ............................................................................... 7

1.3. Product Support Business Case Analysis (PS-BCA). .............................................. 8

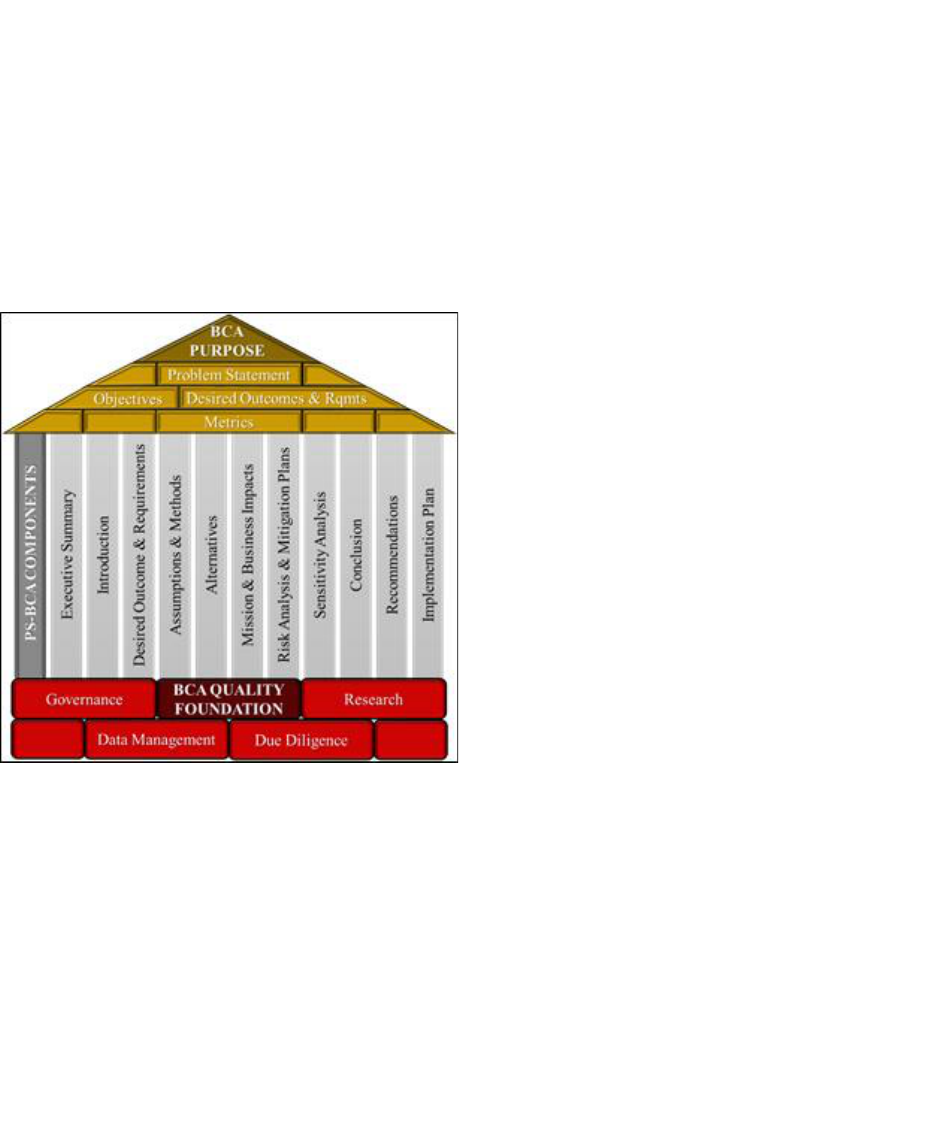

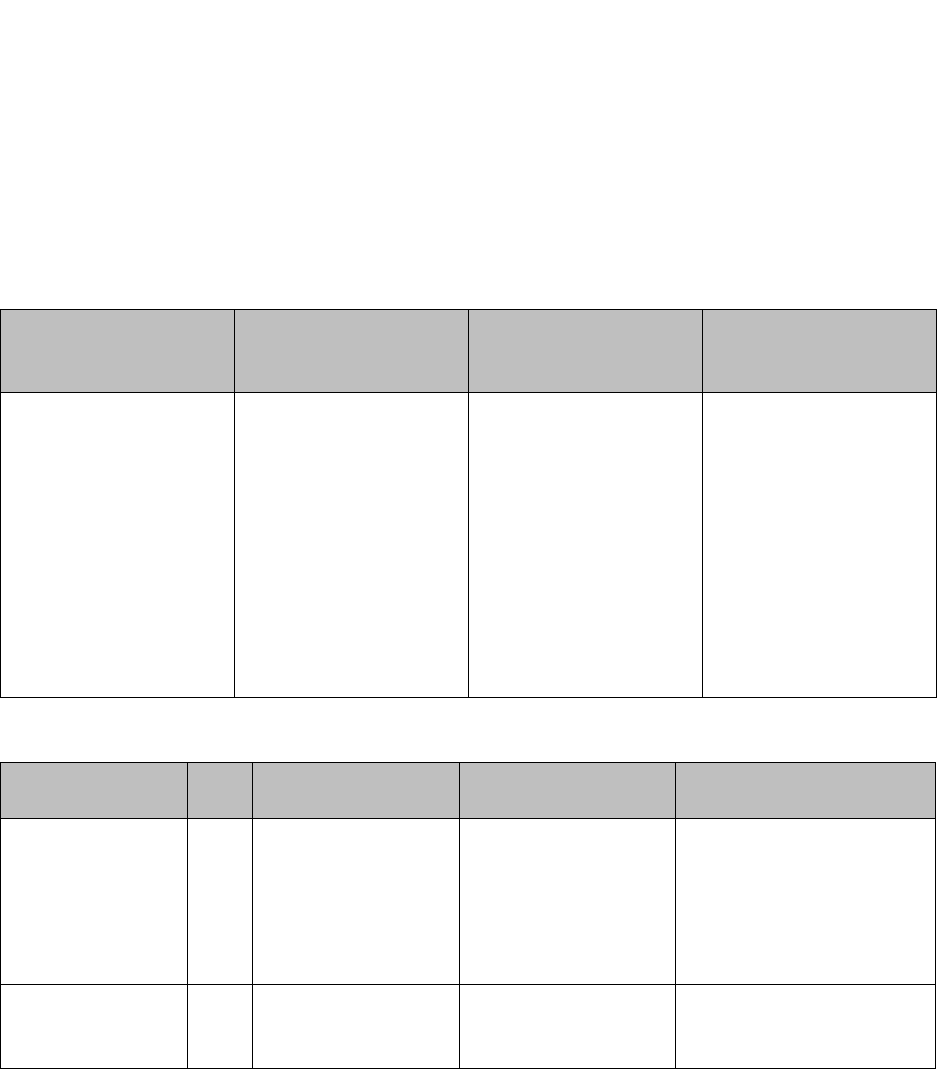

Figure 1.1. Product Support BCA Elements. ............................................................................. 9

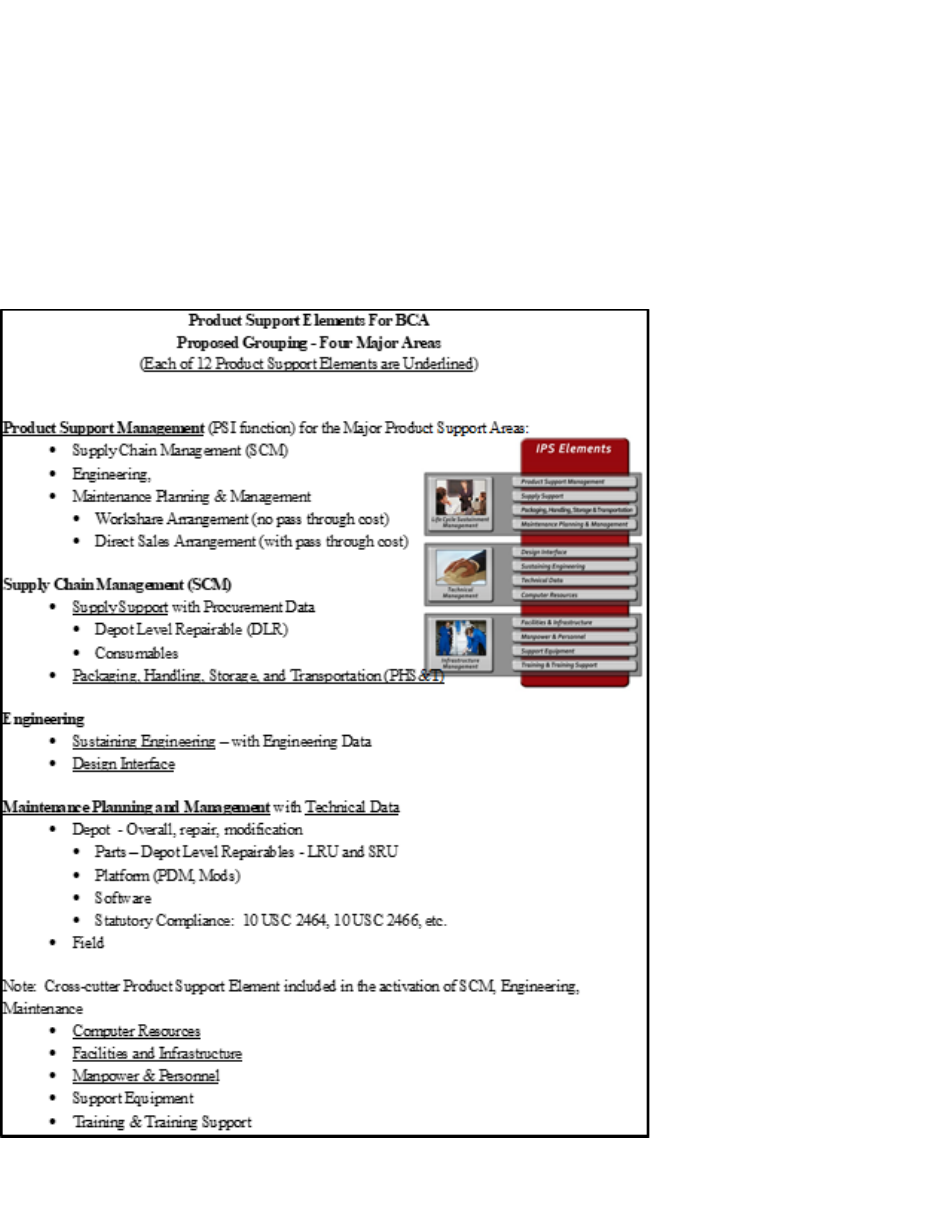

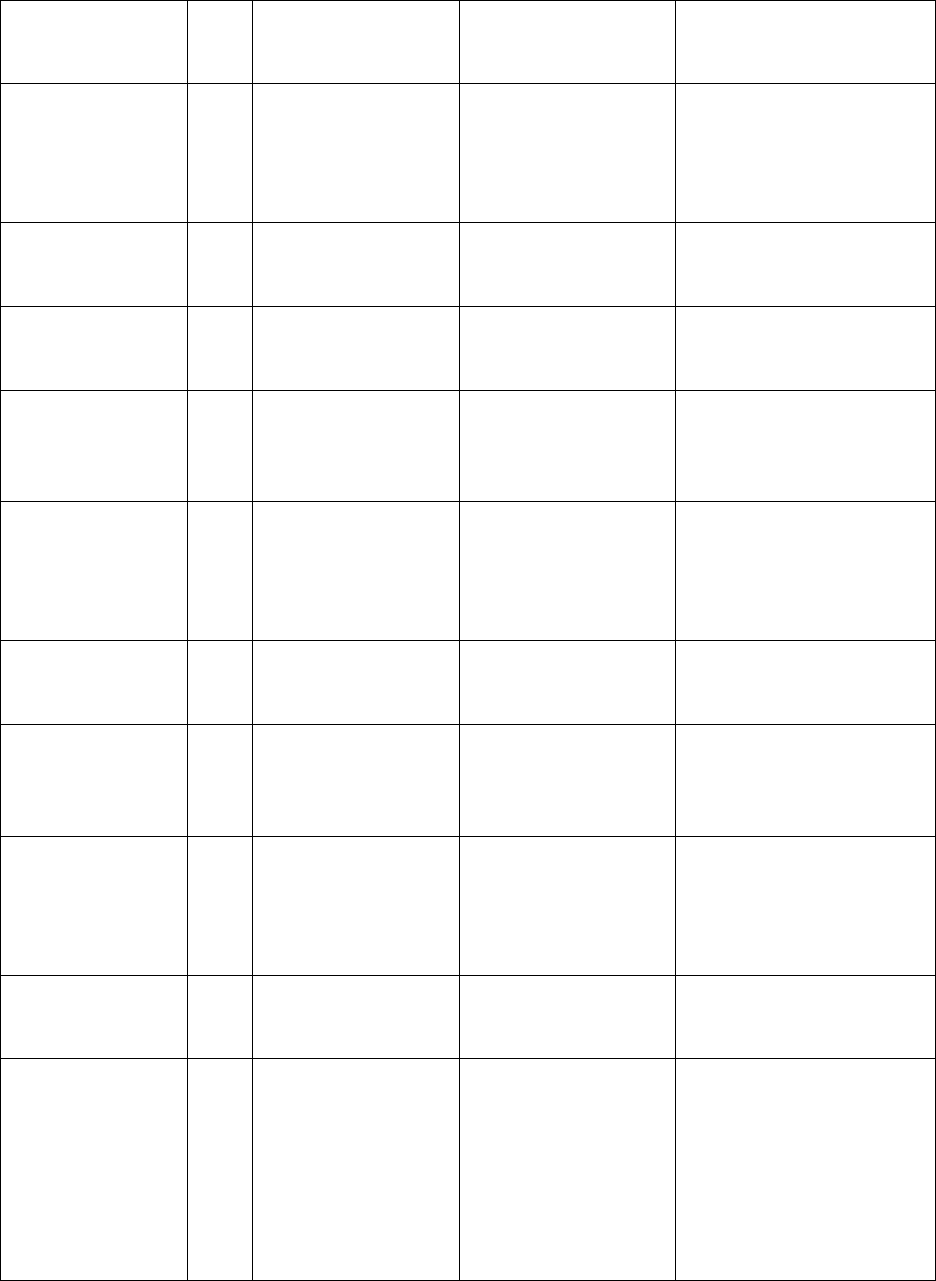

Figure 1.2. Four Major Areas for 12 IPS Elements. ................................................................... 10

1.4. When to Conduct a PS-BCA.................................................................................... 11

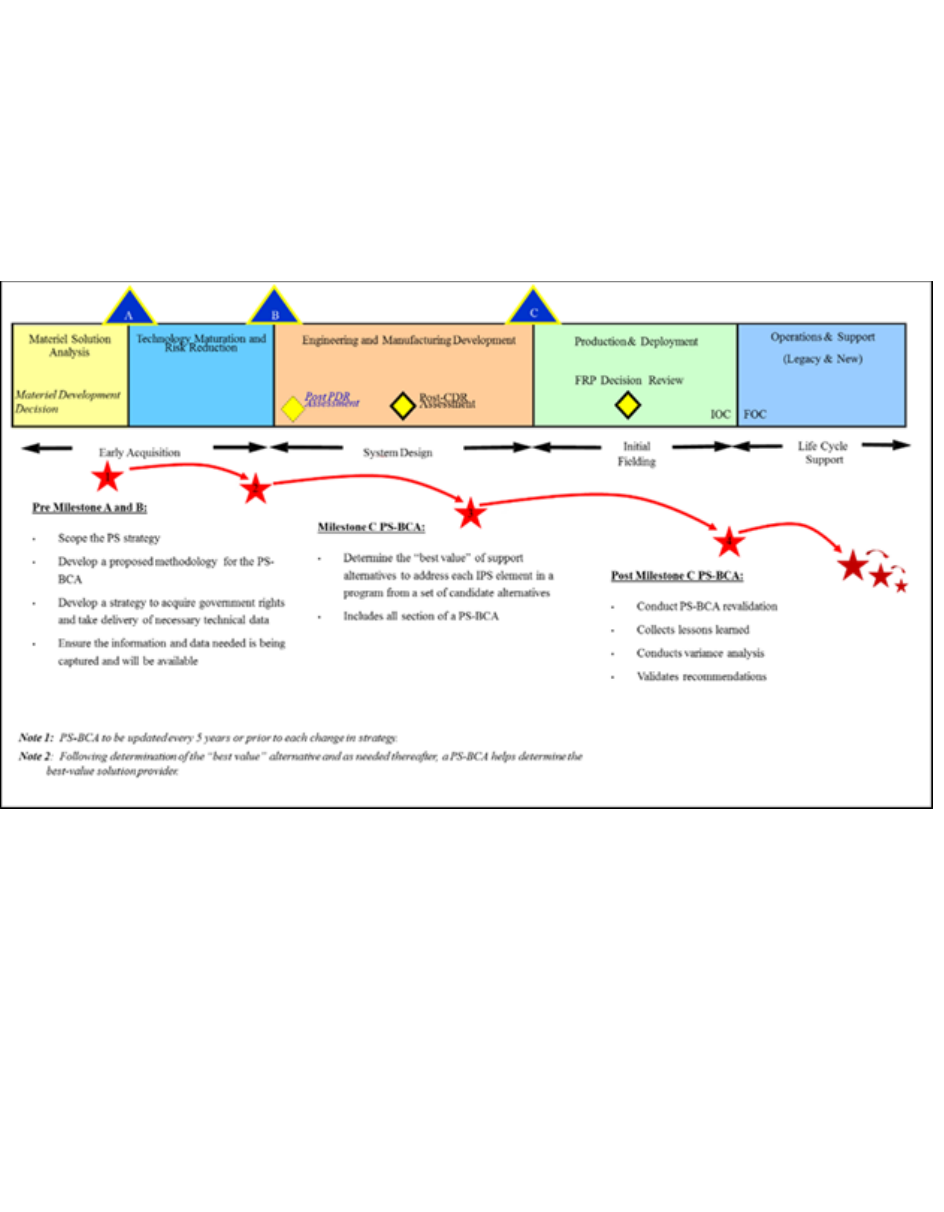

Figure 1.3. PS-BCA Schedule Throughout the Life Cycle. ....................................................... 12

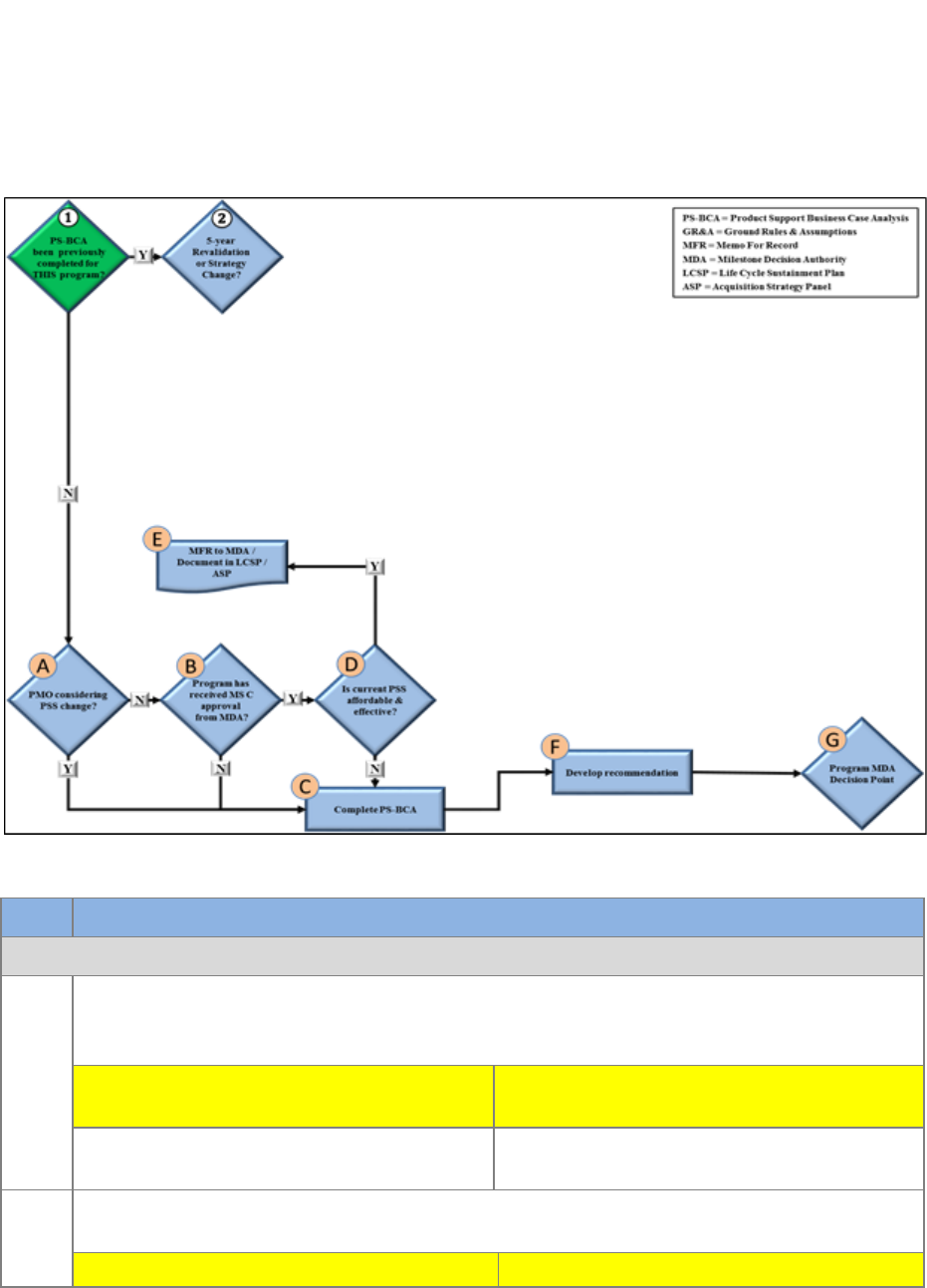

Figure 1.4. Step #1 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree. .................................................................... 13

Table 1.1. Step #1 Decision Tree Process Flow. ...................................................................... 13

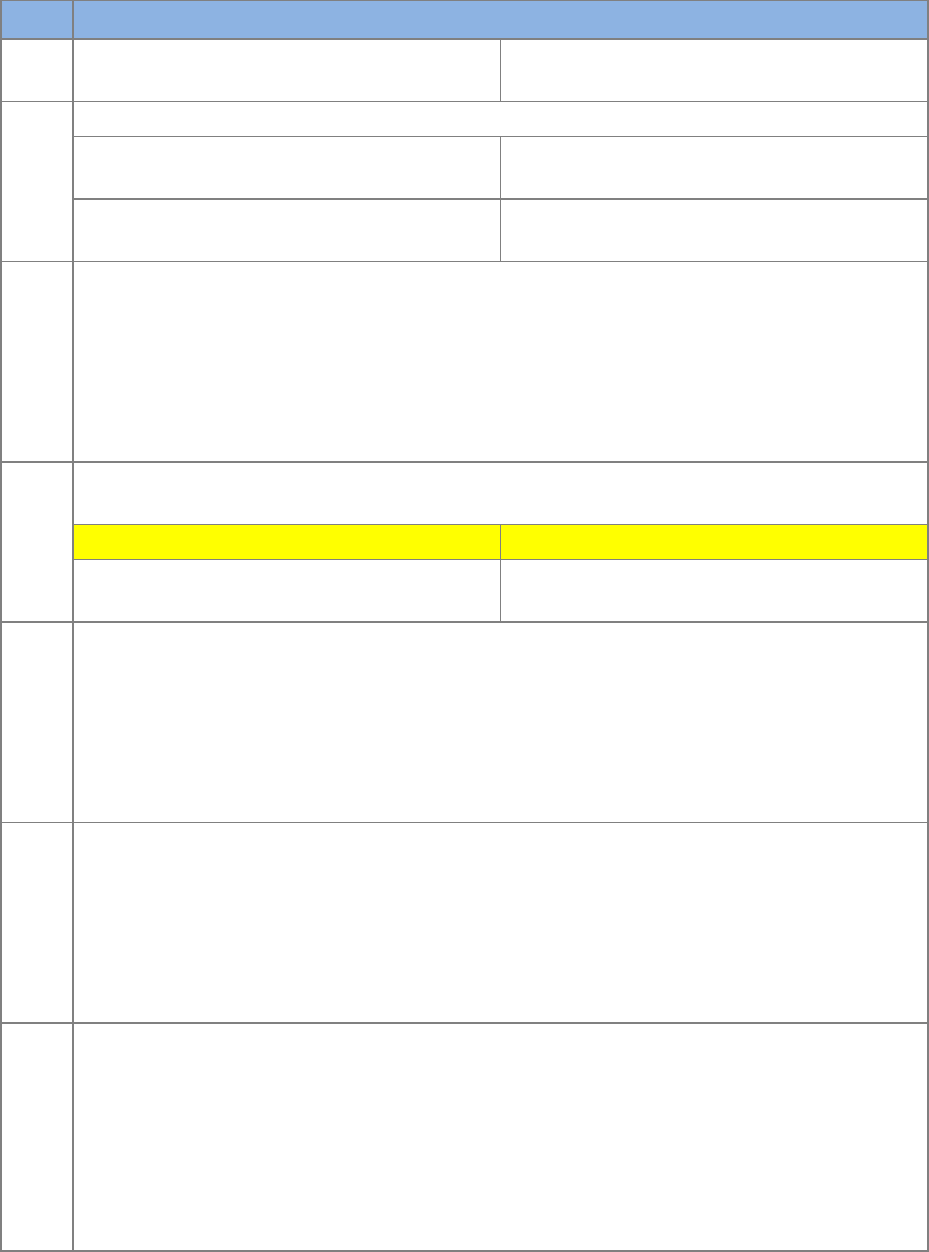

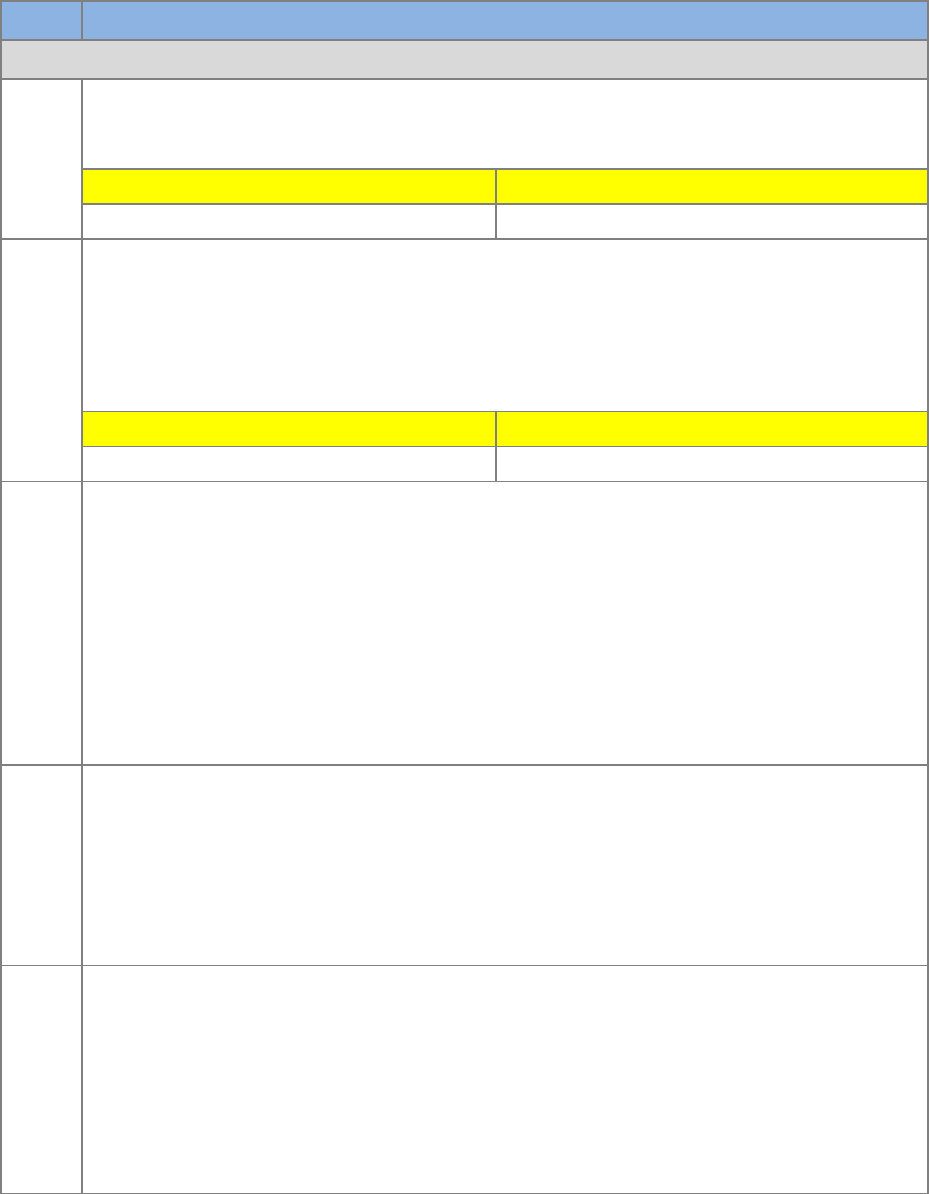

Figure 1.5. Step #2 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree. .................................................................... 15

Table 1.2. Step #2 Decision Tree Process Flow. ...................................................................... 15

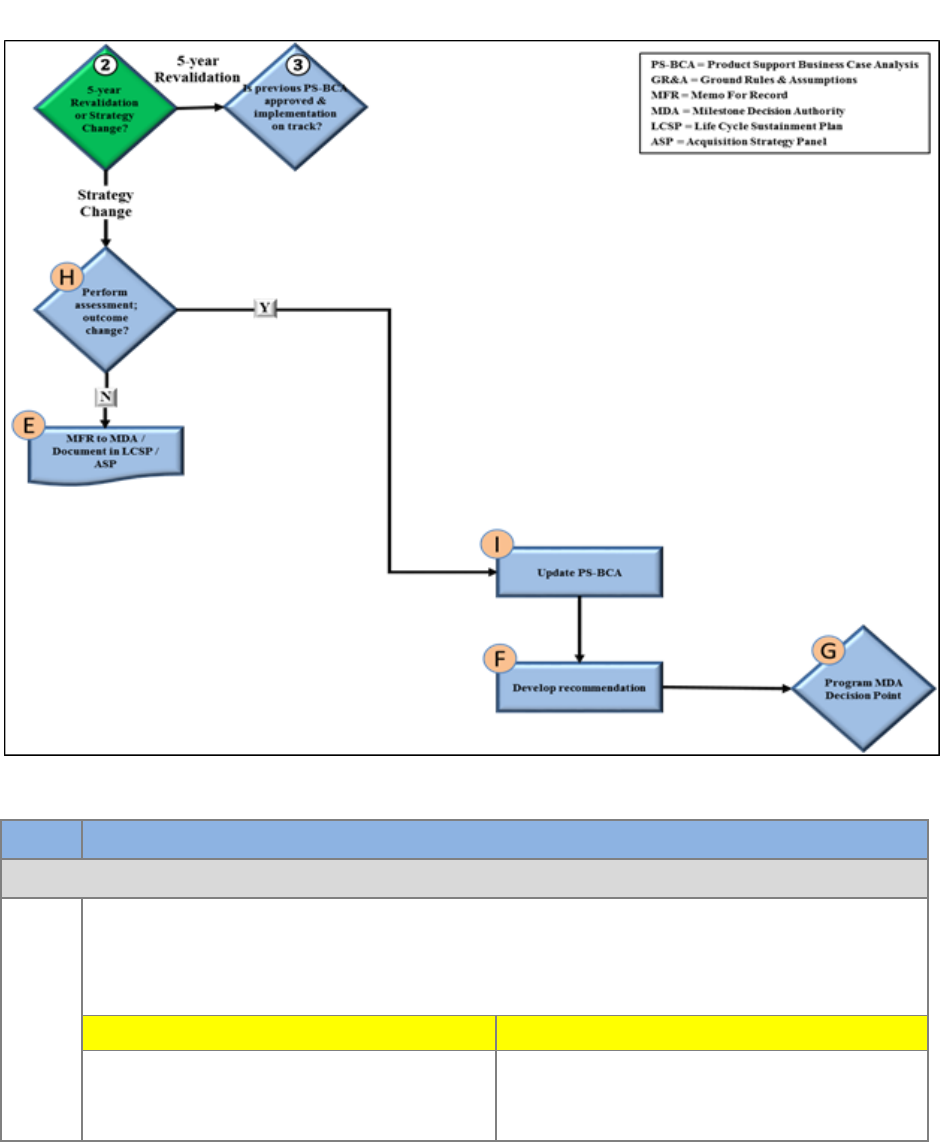

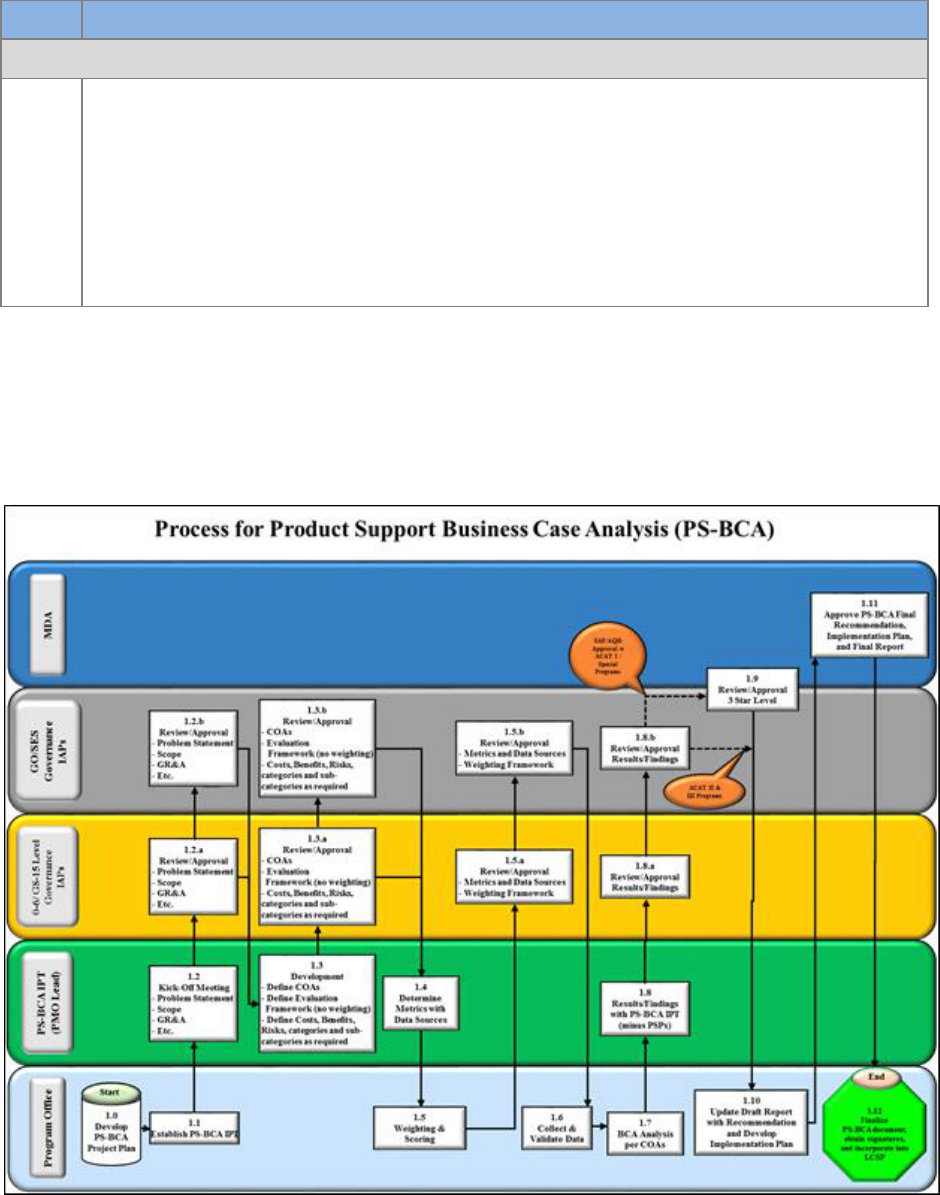

Figure 1.6. Step #3 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree. .................................................................... 17

Table 1.3. Step #3 Decision Tree Process Flow. ...................................................................... 17

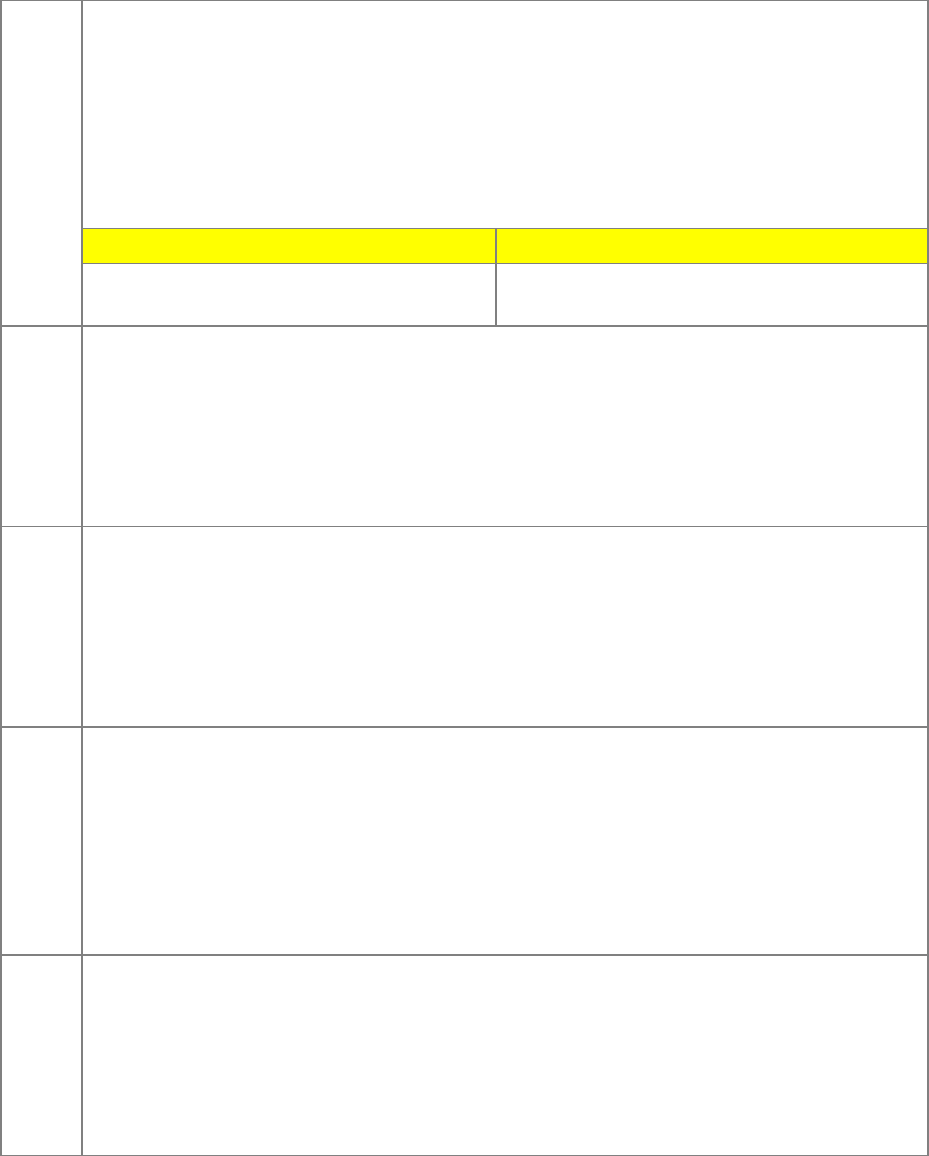

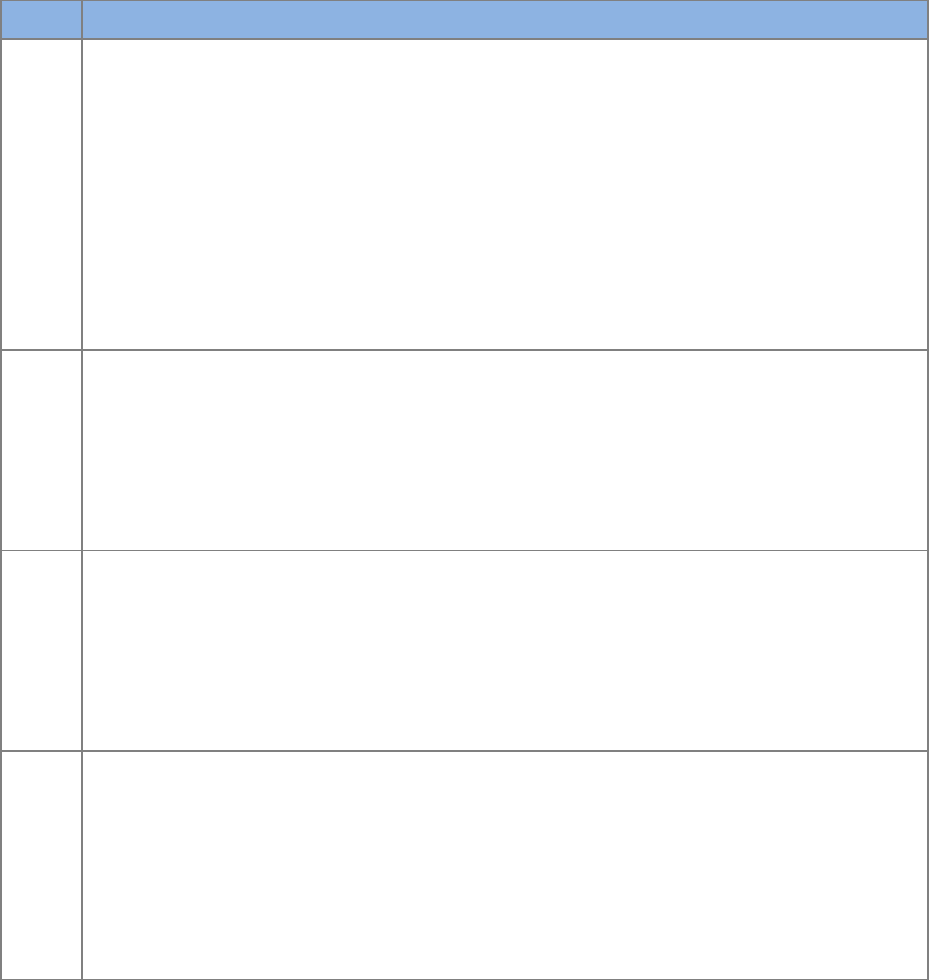

Figure 1.7. Step #4 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree. .................................................................... 19

Table 1.4. Step #4 Decision Tree Process Flow. ...................................................................... 19

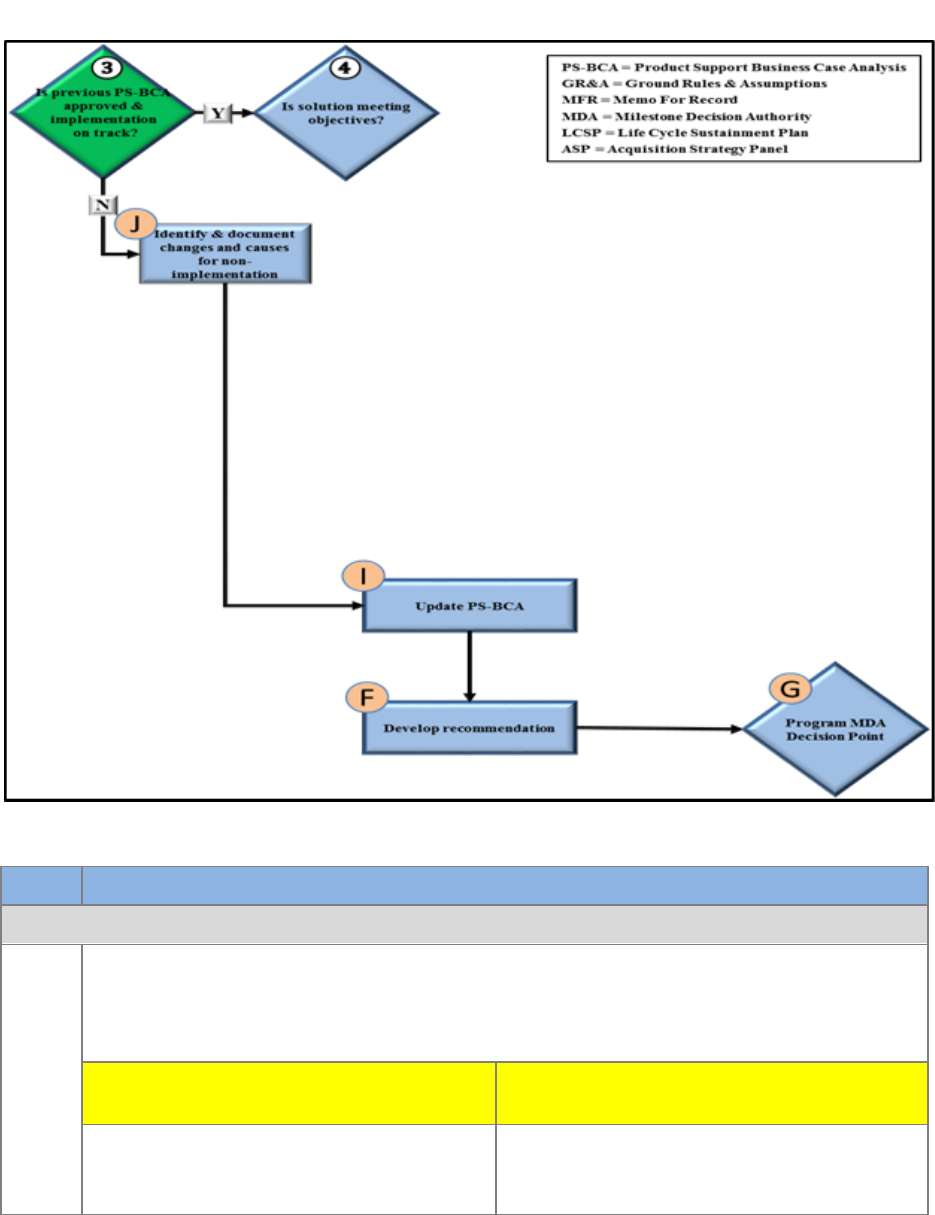

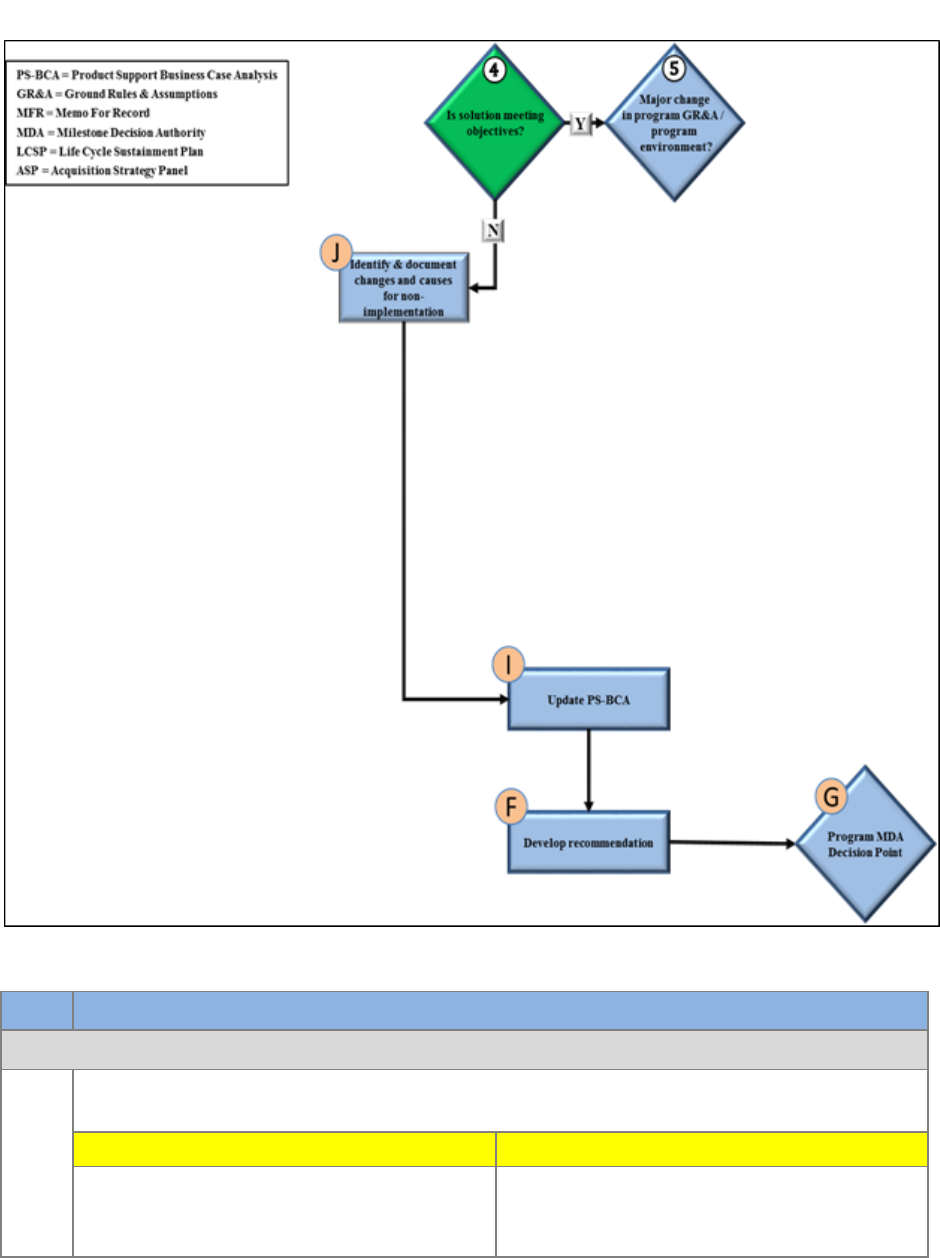

Figure 1.8. Step #5 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree. .................................................................... 21

Table 1.5. Step #5 Decision Tree Process Flow. ...................................................................... 21

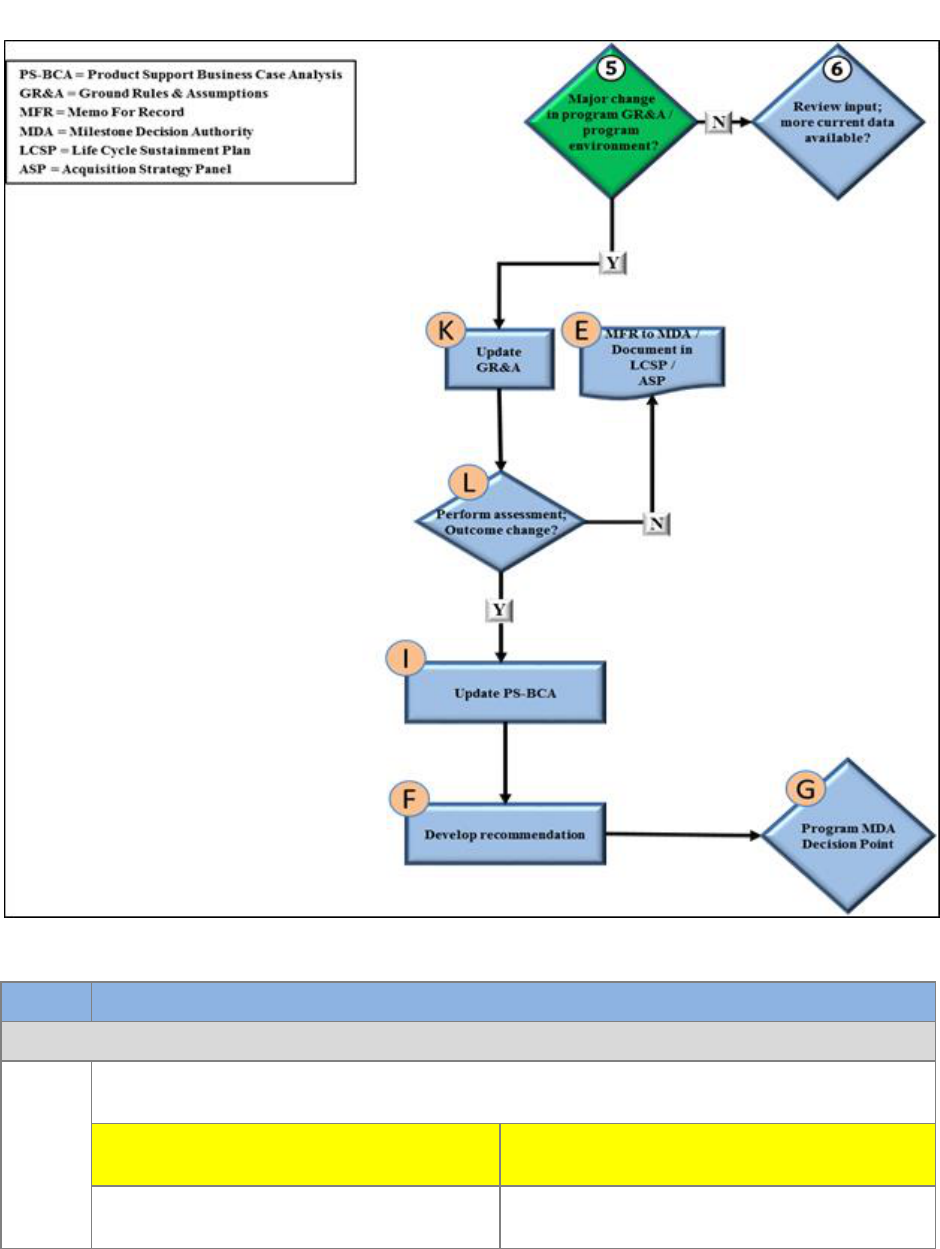

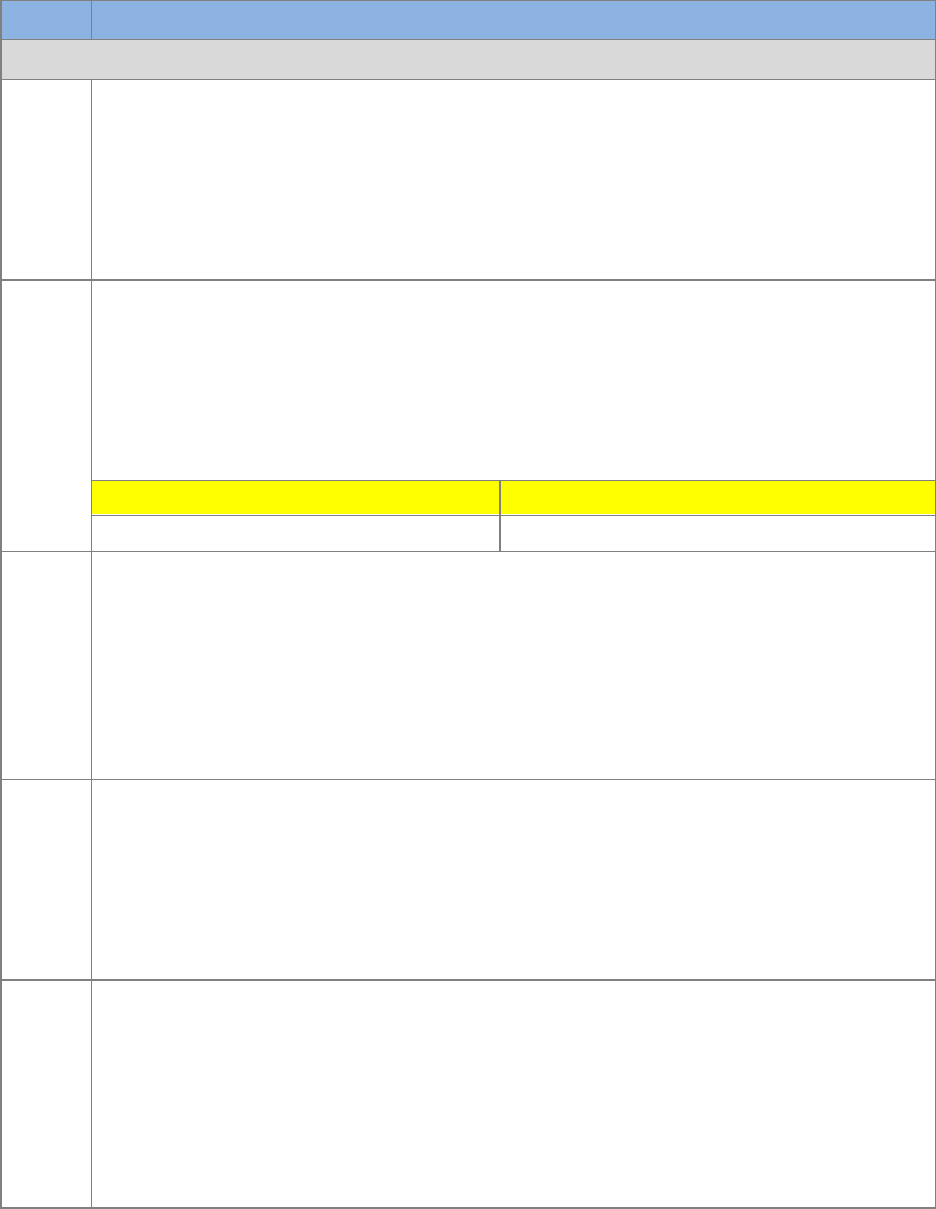

Figure 1.9. Step #6 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree. .................................................................... 23

Table 1.6. Step #6 Decision Tree Process Flow. ...................................................................... 24

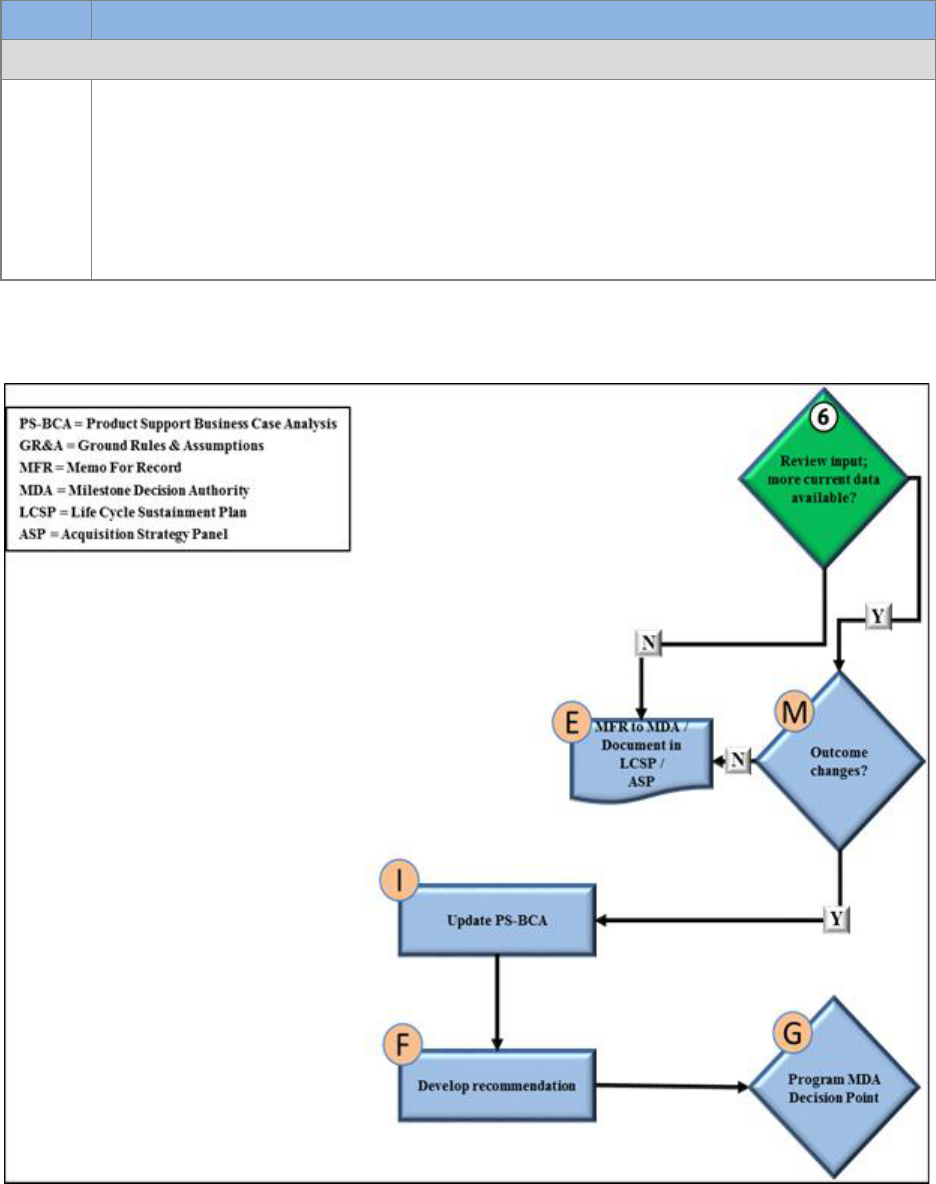

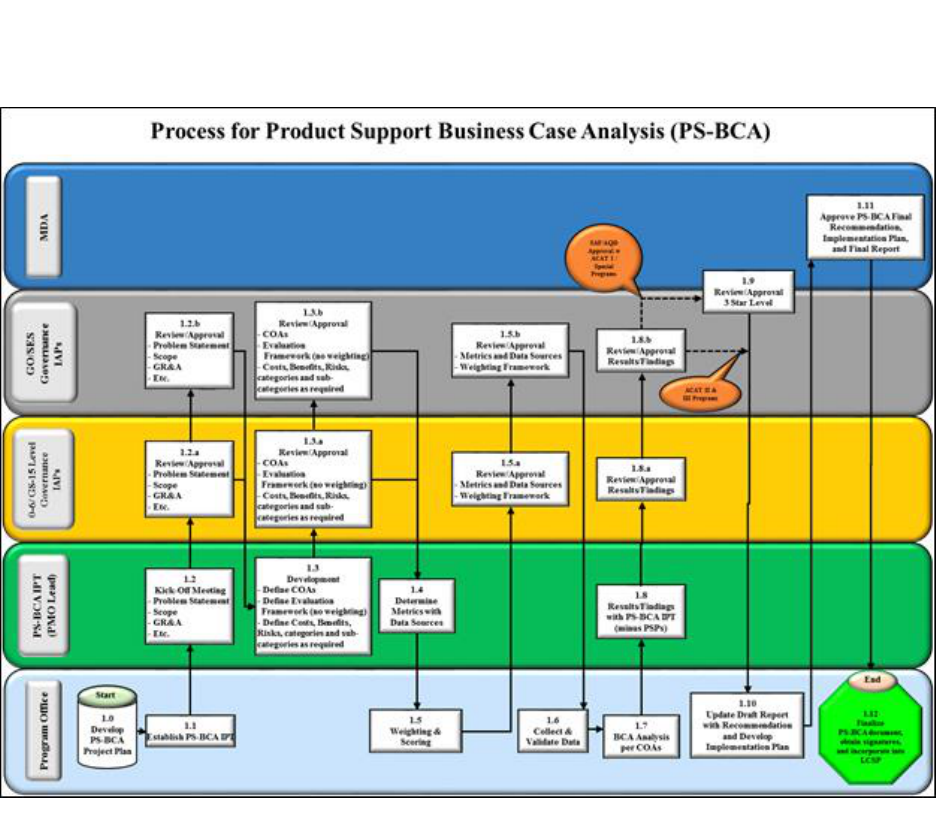

1.5. PS-BCA Process Overview...................................................................................... 25

Figure 1.10. PS-BCA Process Map. ............................................................................................. 25

Chapter 2—ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES 26

2.1. PS-BCA IPT Members. ........................................................................................... 26

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 3

2.2. Approval Level. ....................................................................................................... 26

2.3. Milestone Decision Authority (MDA). .................................................................... 26

2.4. Governance Structure. ............................................................................................. 27

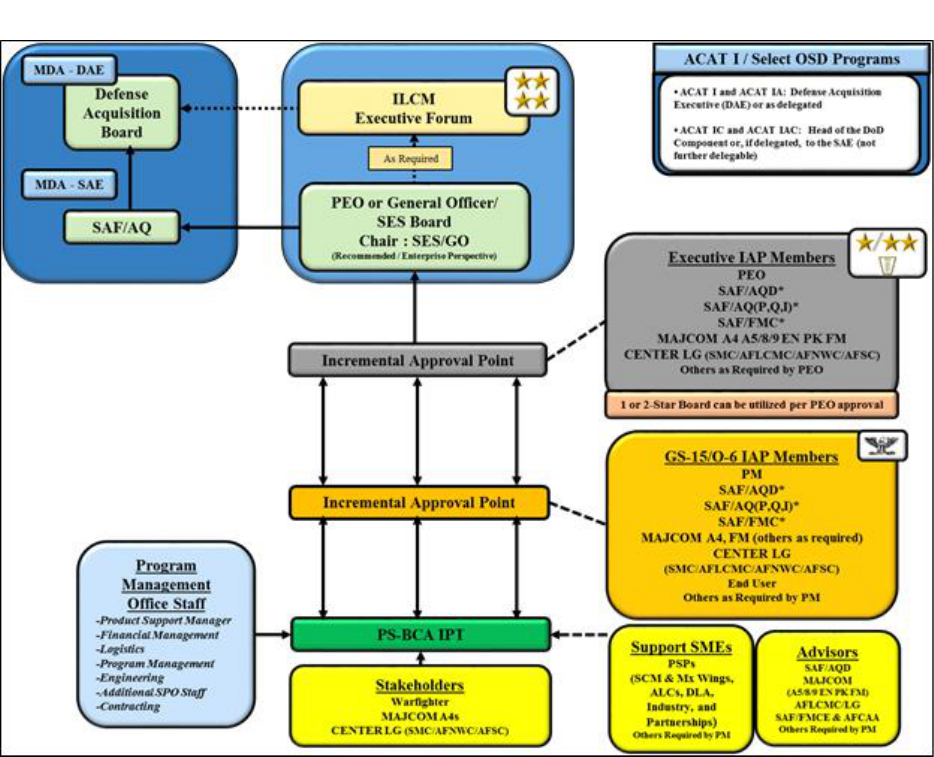

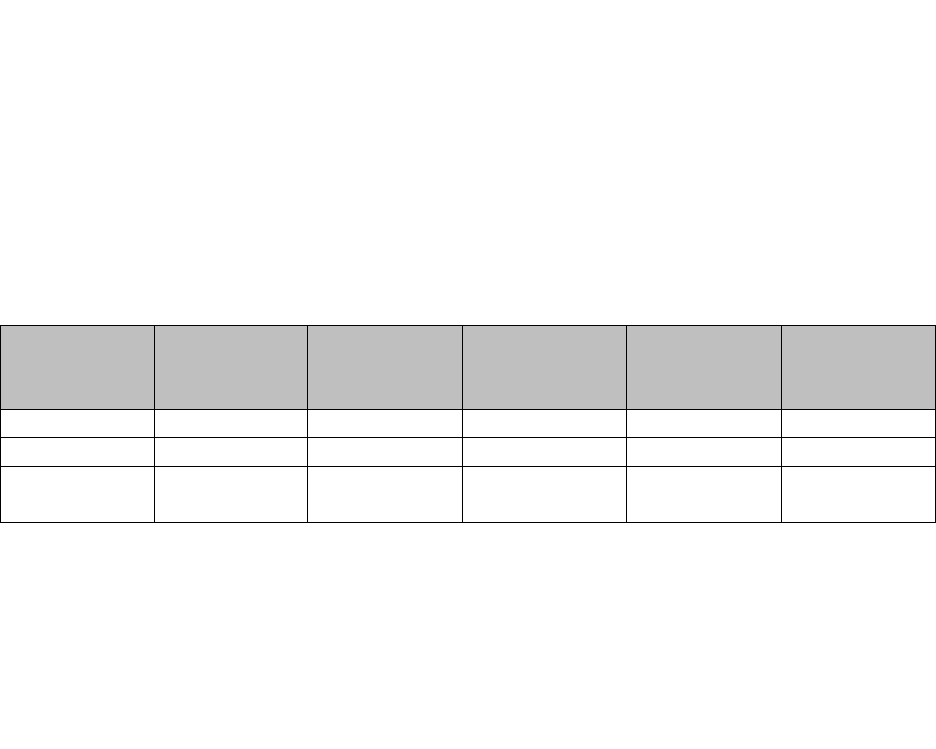

Figure 2.1. MDAP/MAIS ACAT I and Special Interest OSD Programs. .................................. 28

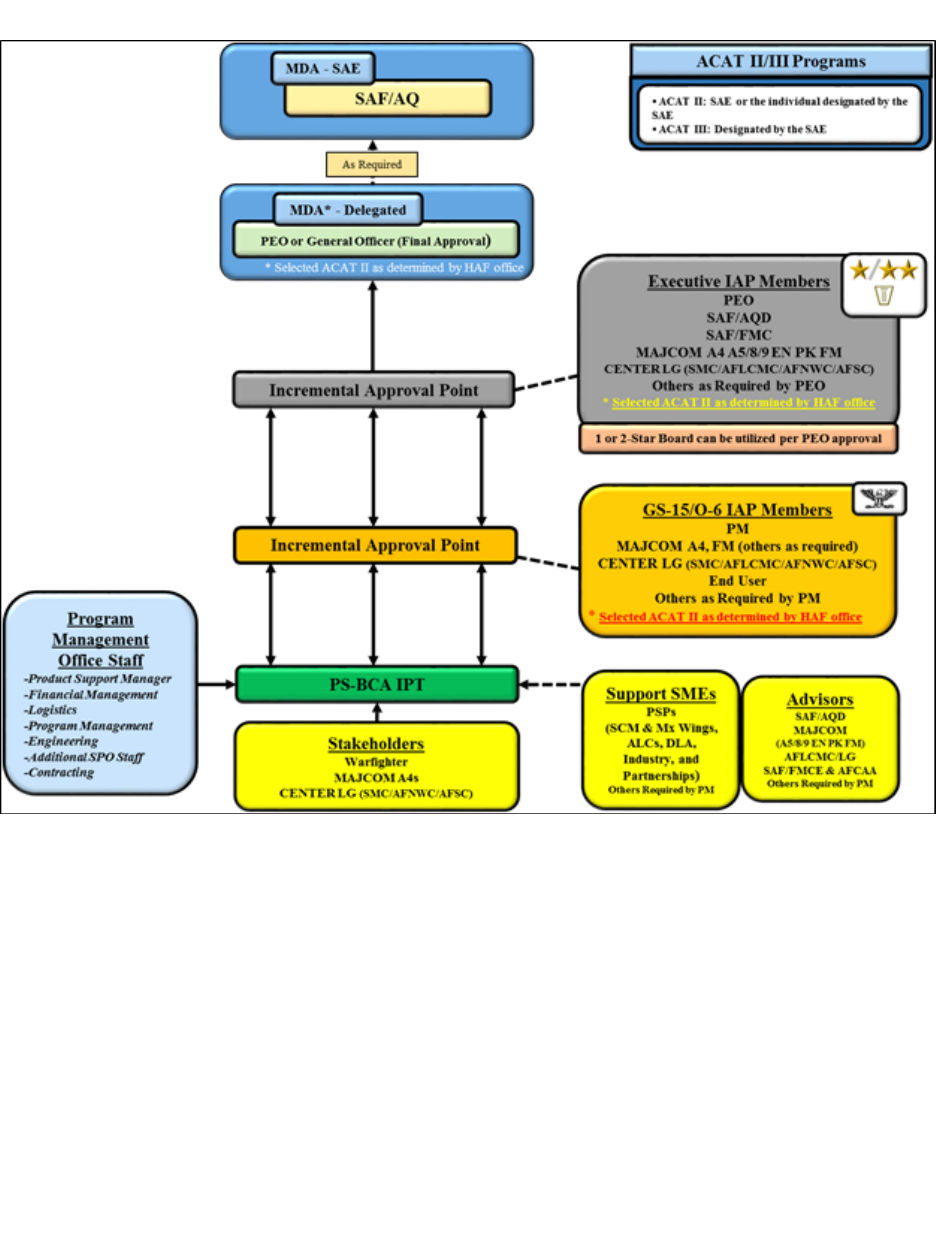

Figure 2.2. ACAT II and III Programs. ...................................................................................... 29

2.5. PS-BCA IPT Roles, Responsibilities, and Functions. ............................................. 31

Chapter 3—PLANNING FOR THE PRODUCT SUPPORT BUSINESS CASE ANALYSIS. 38

3.1. PS-BCA IPT Kickoff Meeting. ................................................................................ 38

3.2. Preparation for Kickoff Meeting. ............................................................................. 38

3.3. Identify and Establish the PS-BCA IPT. .................................................................. 39

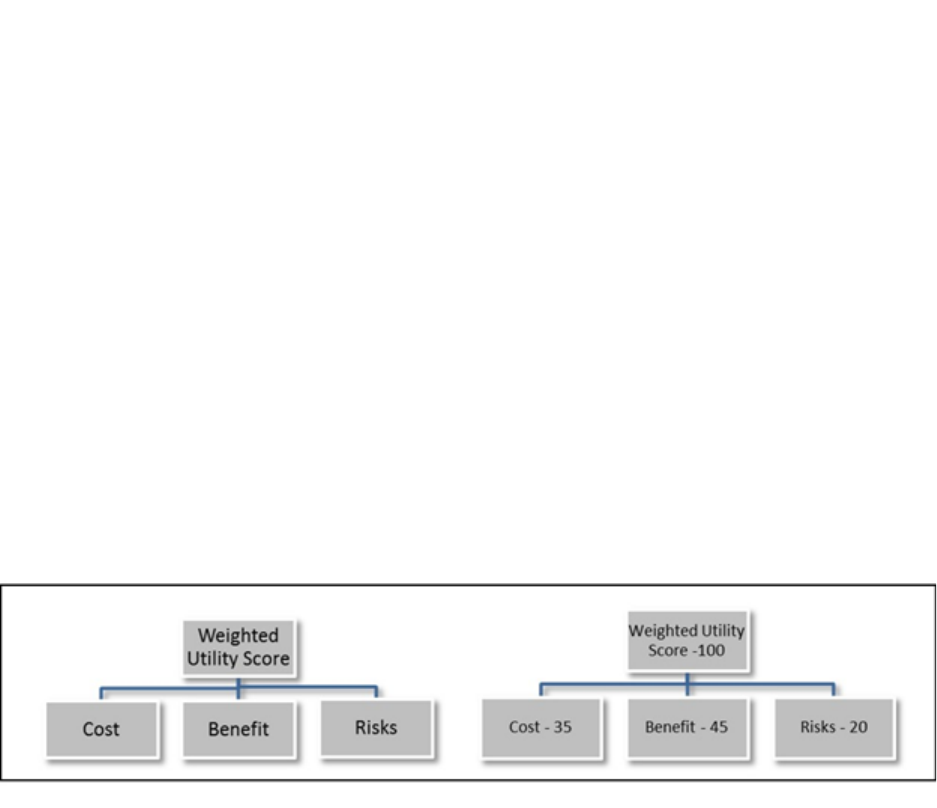

Table 3.1. IPT Membership. ..................................................................................................... 39

3.4. Kickoff Meeting. ...................................................................................................... 41

Table 3.2. Integrated Product Support (IPS) Element Categorization. ..................................... 43

Chapter 4—COURSES OF ACTION 48

4.1. Introduction. ............................................................................................................. 48

4.2. Status Quo ................................................................................................................ 48

4.3. Future State COAs. .................................................................................................. 48

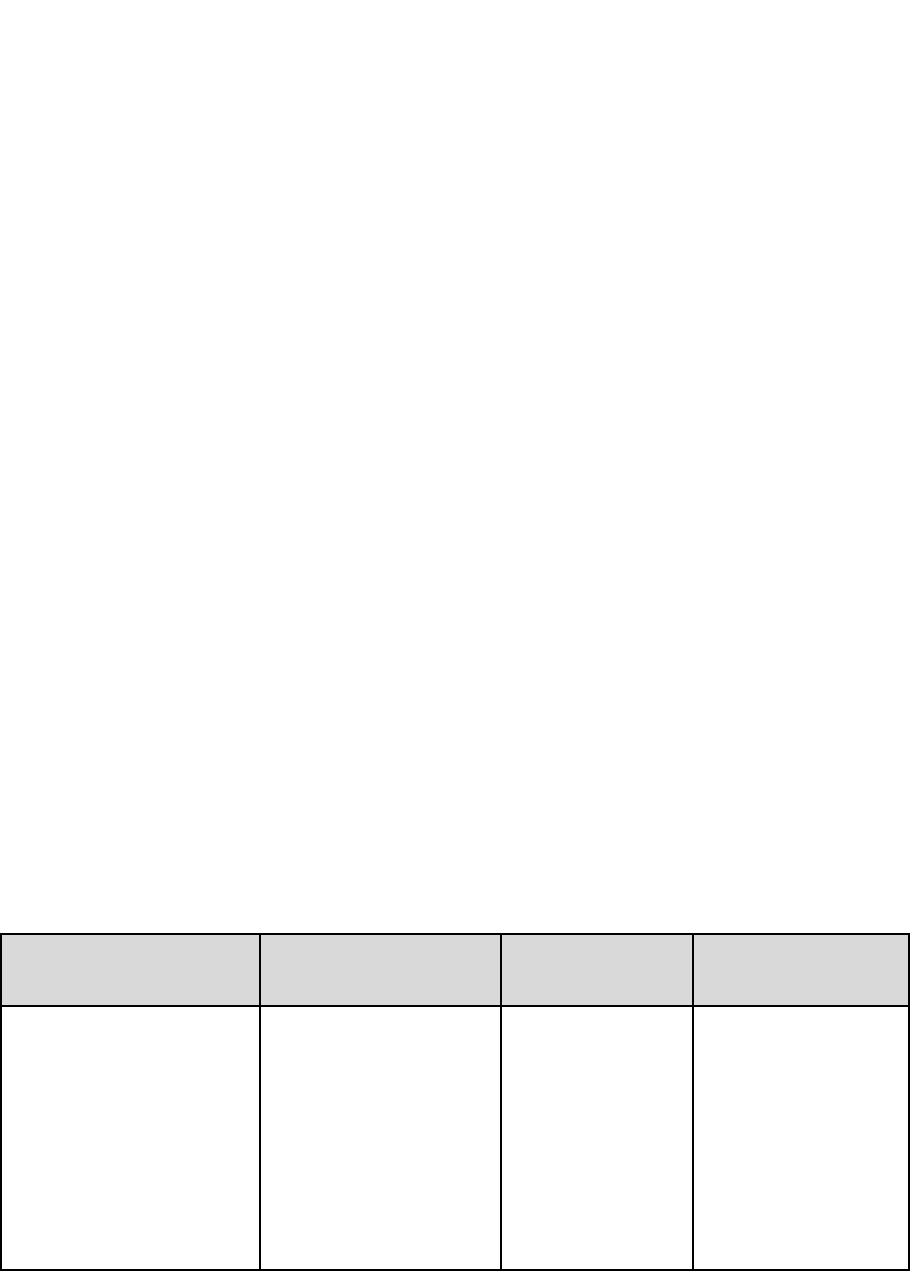

Table 4.1. Holistic Approach. ................................................................................................... 49

Table 4.2. Modular Approach. .................................................................................................. 49

4.4. Reasonableness and Feasibility. ............................................................................... 50

Chapter 5—BENEFITS AND NON-FINANCIAL ANALYSIS 53

5.1. Benefits Introduction. .............................................................................................. 53

5.2. Selecting Benefits. ................................................................................................... 53

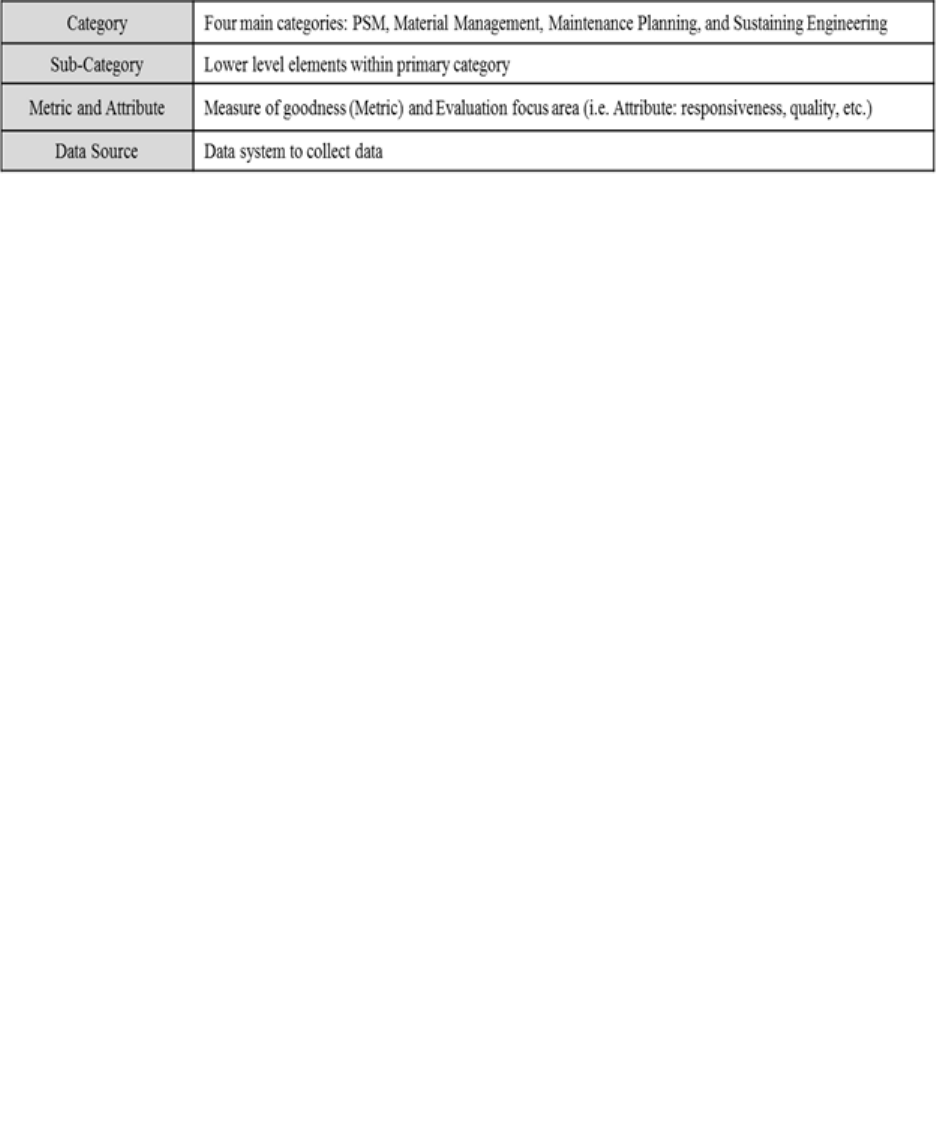

Table 5.1. Category Metric Attribute. ....................................................................................... 54

5.3. Quantitative Benefits and Metrics. .......................................................................... 54

Table 5.2. Quantitative Benefits and Associated Metrics. ........................................................ 55

5.4. Qualitative Benefits and Metrics. ............................................................................ 55

Chapter 6—COST AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS 57

6.1. PS-BCA Cost Estimates. .......................................................................................... 57

6.2. Criteria 1 – Guided by the Problem Statement. ....................................................... 57

6.3. Criteria 2 – GR&As are Reasonable and Documented. ........................................... 57

6.4. Criteria 3 – Properly Utilizes the Various Types of Analysis. ................................. 58

4 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

6.5. Criteria 4 – Properly Utilizes the Highest Quality Data Available. ......................... 59

6.6. Criteria 5 – Data is Normalized, Projected and Used Correctly. ............................. 59

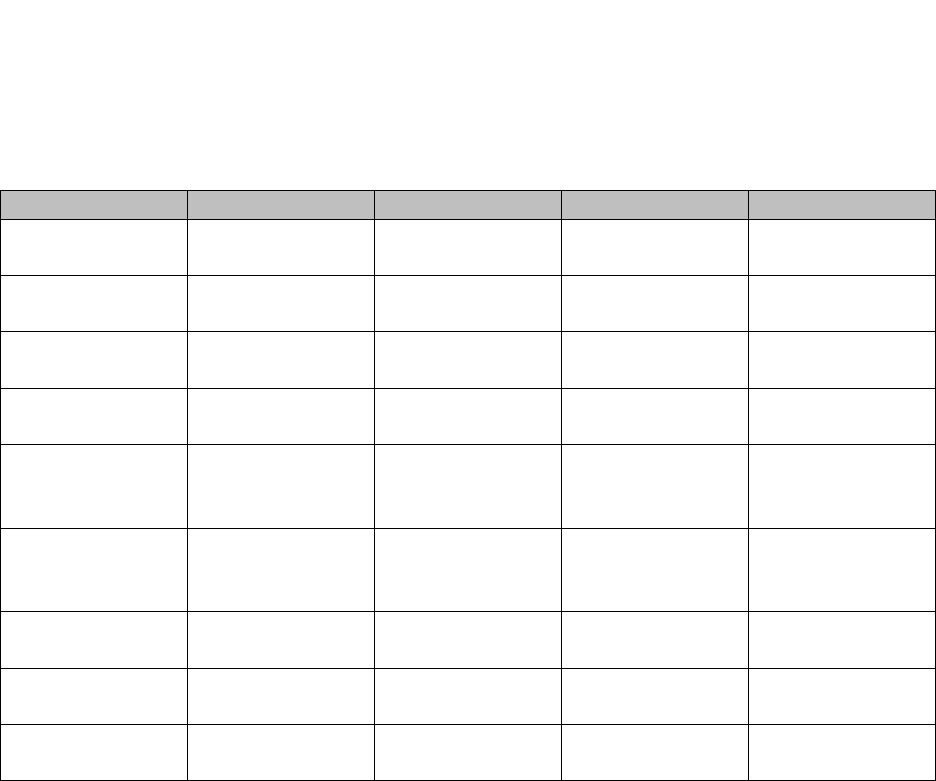

Figure 6.1. Illustration of Inflation, Price Escalation, and Real Price Change. .......................... 60

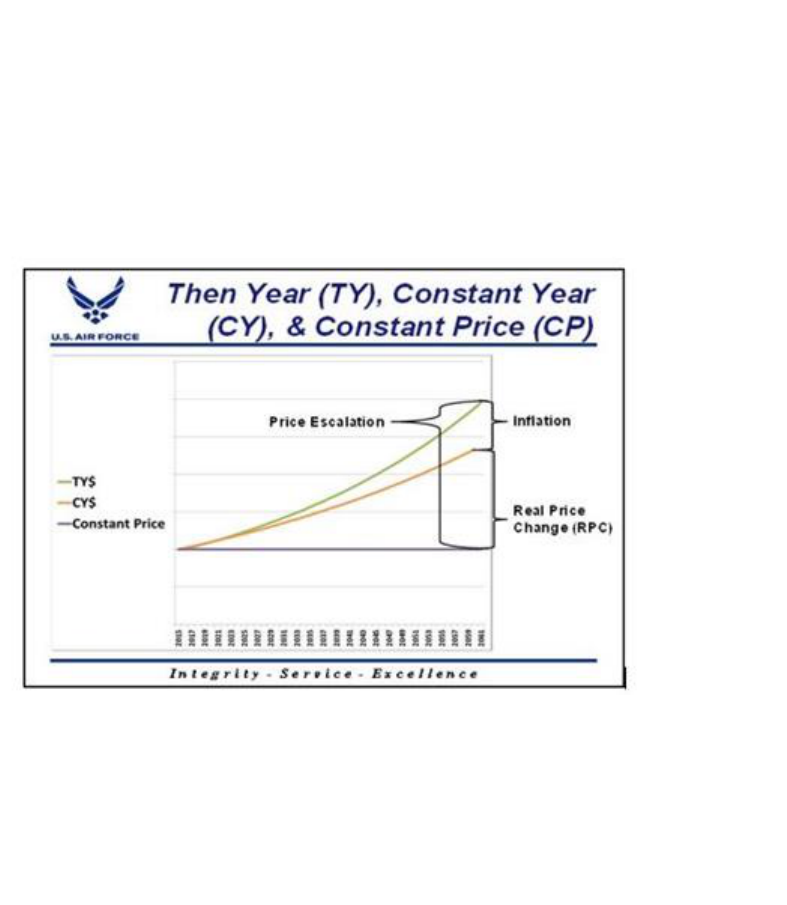

Figure 6.2. Considerations When Normalizing Data for Usage or Quantity (or Duration). ...... 61

6.7. Criteria 6 – Cost Estimates Accurately Represent the PSS for Each COA. ............ 62

6.8. Criteria 7 – Ensure Cost Risk is Handled Consistently for Each COA. .................. 62

6.9. Criteria 8 – Enables Decision Maker to Make the Most Informed Decision

Possible. ................................................................................................................... 63

Chapter 7—RISK ASSESSMENT 64

7.1. Introduction to Risk Assessment. ............................................................................ 64

7.2. Defining Risk. .......................................................................................................... 64

7.3. Progression of Risk. ................................................................................................. 64

7.4. Classifications of Risk. ............................................................................................ 65

7.5. Risk Management Planning. .................................................................................... 65

7.6. Risk Identification. ................................................................................................... 65

7.7. Risk Analysis. .......................................................................................................... 65

7.8. Risk Handling Planning & Implementation. ............................................................ 66

7.9. Risk Tracking. .......................................................................................................... 67

7.10. Risk Management Summary. ................................................................................... 67

Chapter 8—DETERMINING EVALUATION FRAMEWORK, WEIGHTING, AND

SCORING 68

8.1. Weighted Utility Score (WUS) and Multi-Objective Decision Analysis (MODA). 68

8.2. COA Evaluation. ...................................................................................................... 68

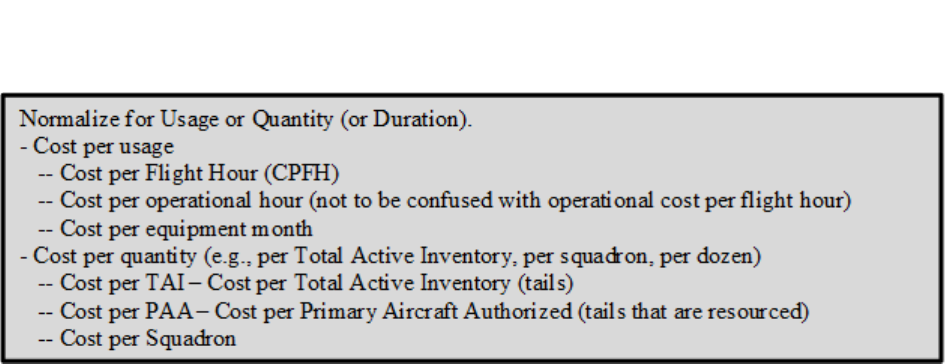

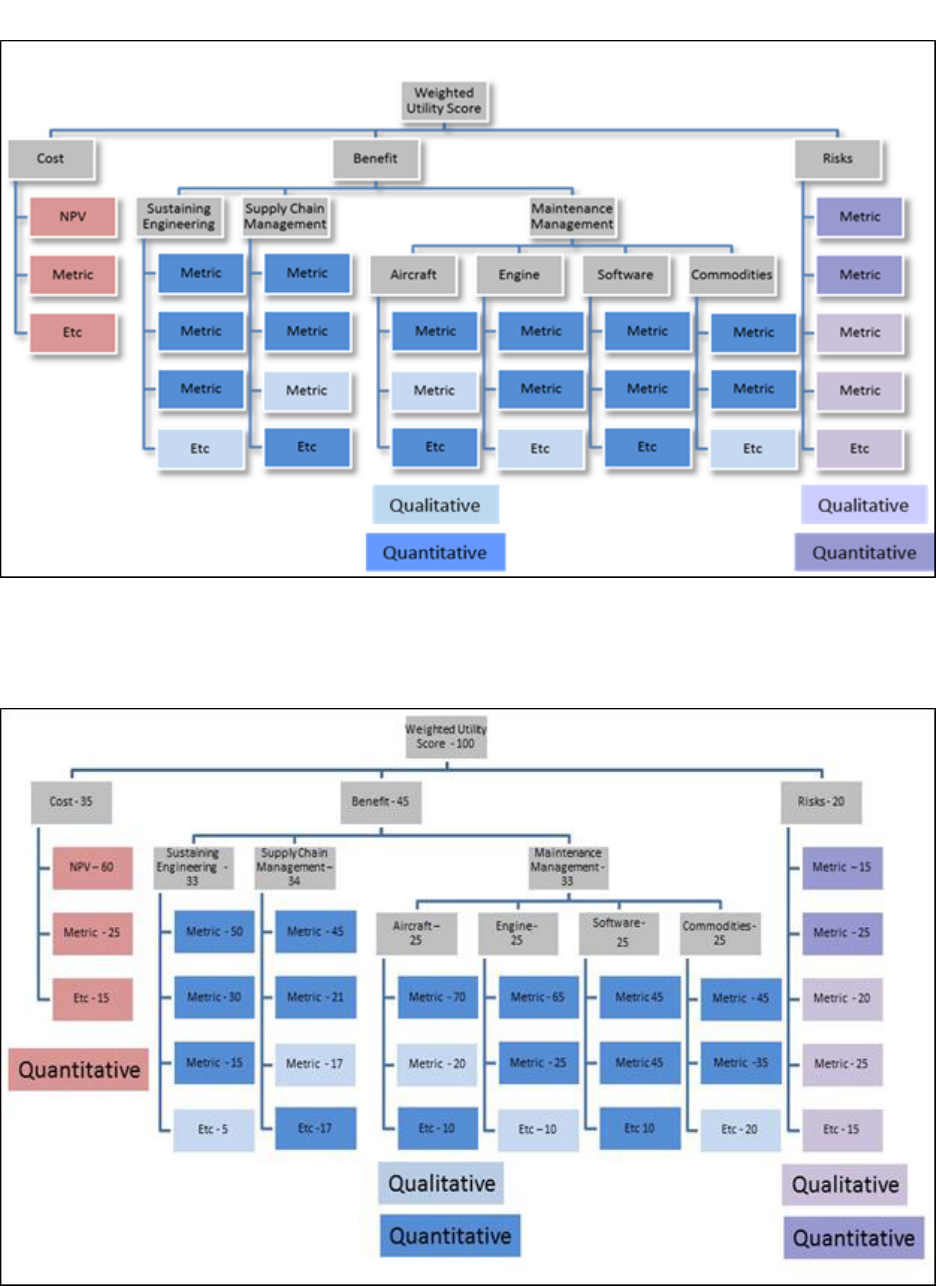

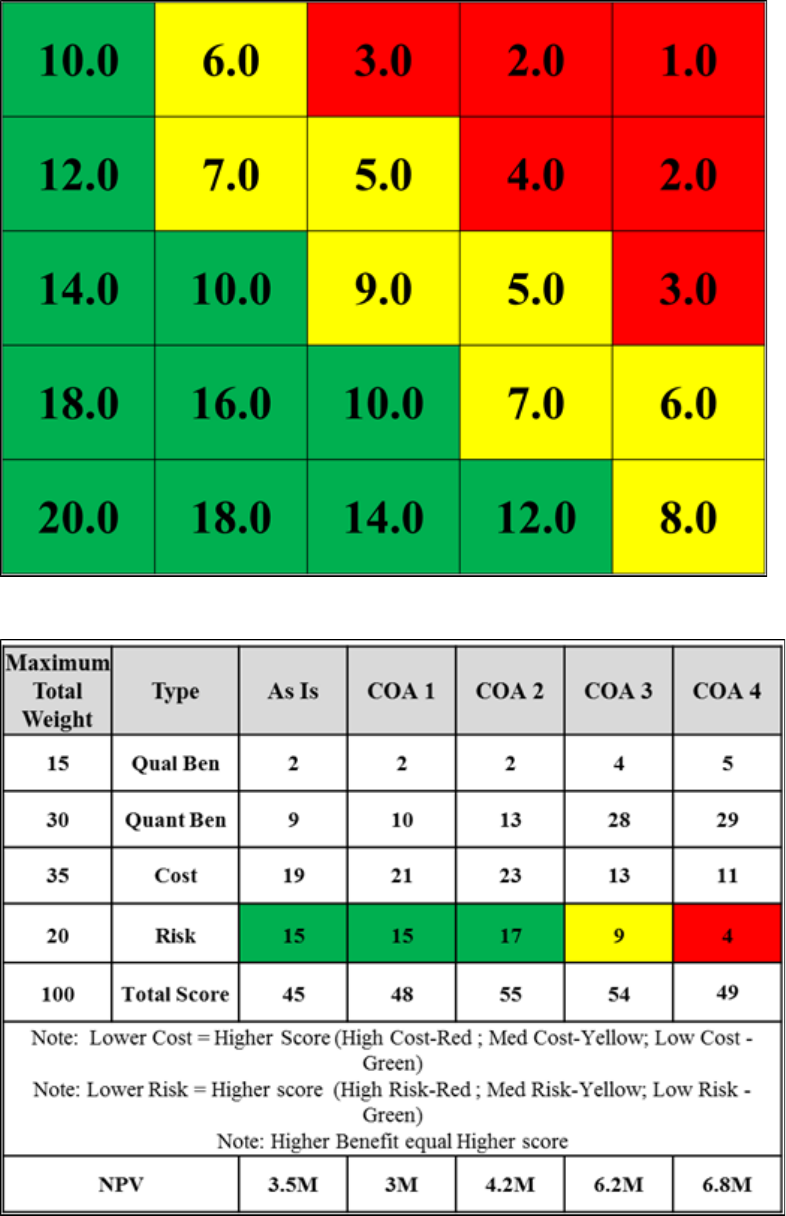

Figure 8.1. Weighted Utility Score (WUS). ............................................................................... 68

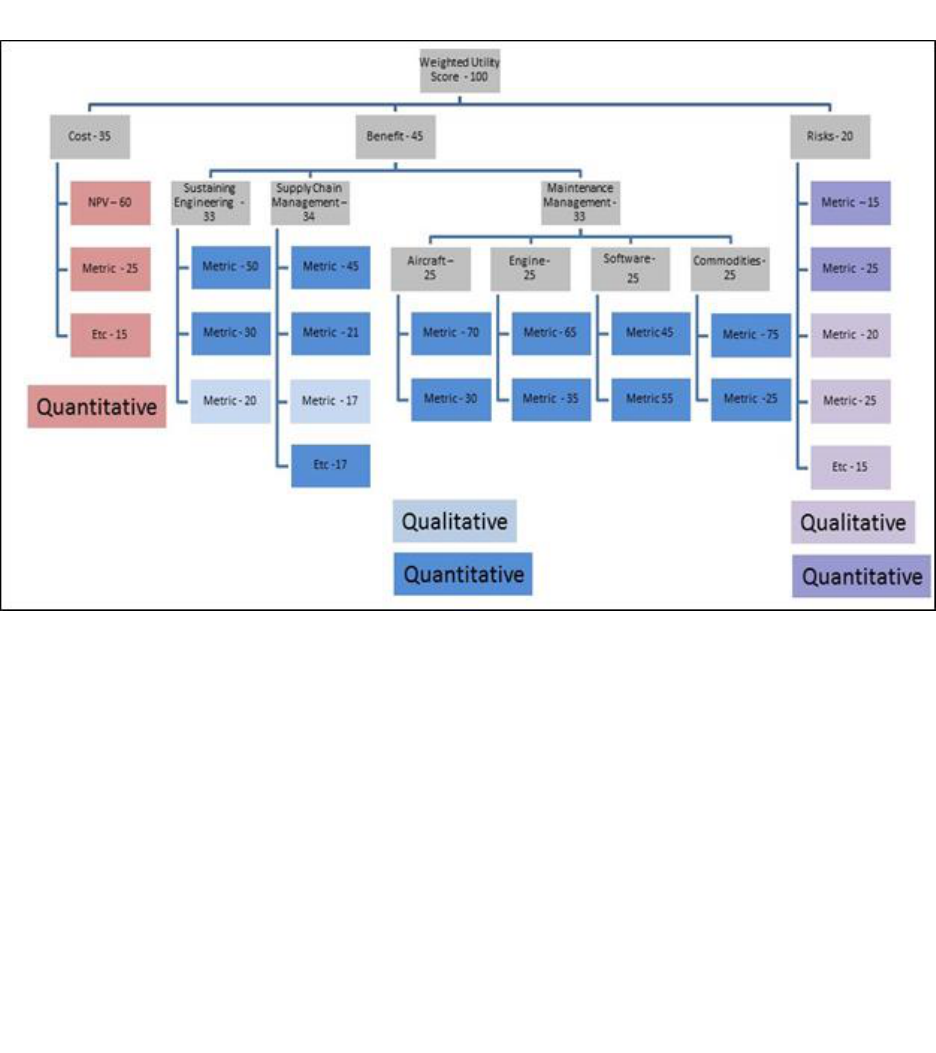

Figure 8.2. WUS Framework - No Weighting Assigned. .......................................................... 69

Figure 8.3. WUS Framework – Criteria Weighting (Notional Data). ........................................ 69

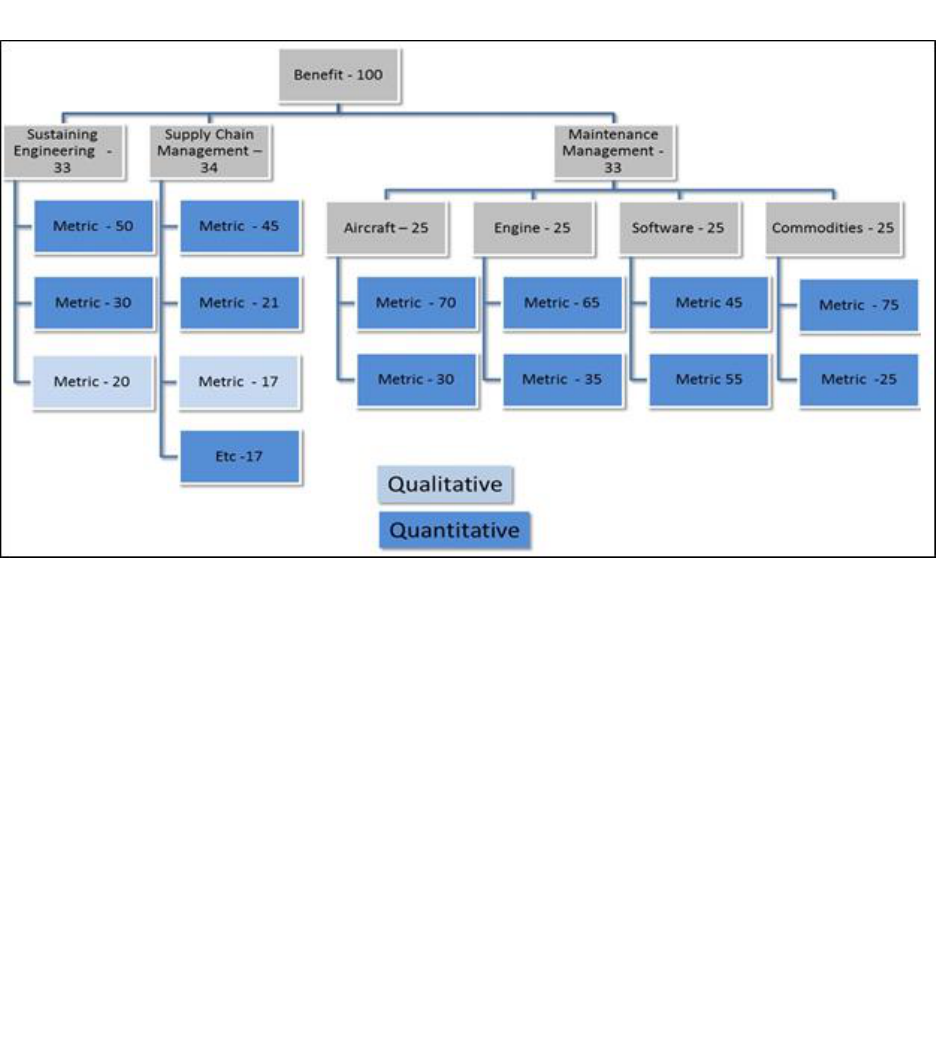

Figure 8.4. MODA Framework – Criteria Weighting (Notional Data). ..................................... 70

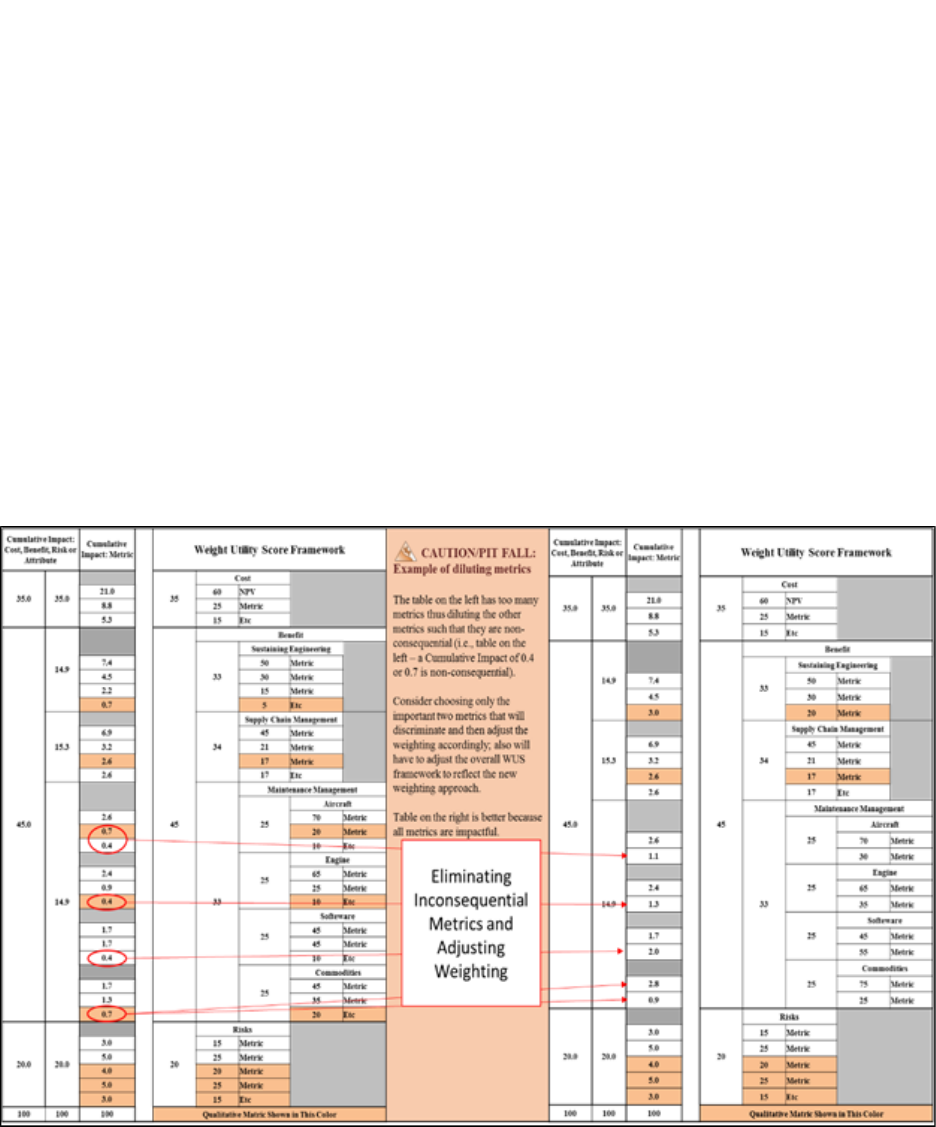

8.3. Steps to Build the WUS or MODA Framework. ..................................................... 70

Figure 8.5. Cumulative Impacts of WUS. .................................................................................. 72

Figure 8.6. Updated WUS Framework. ...................................................................................... 73

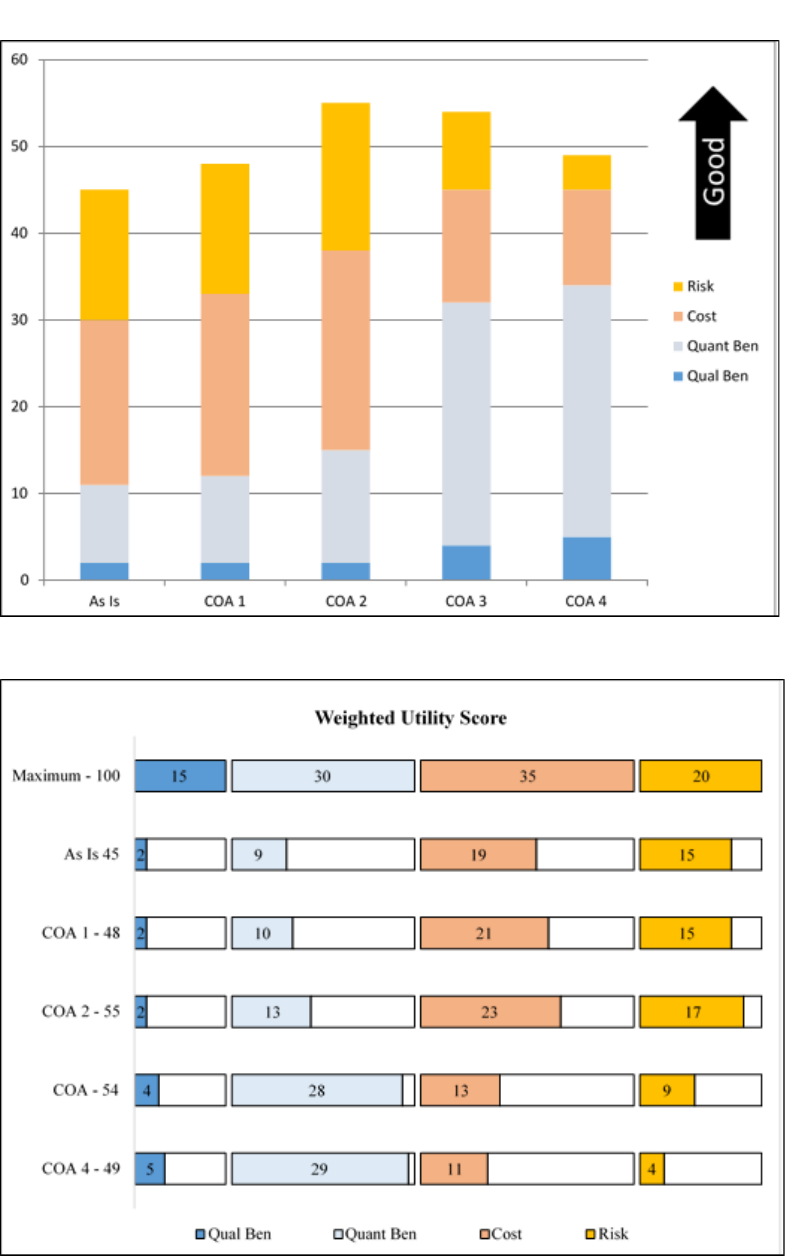

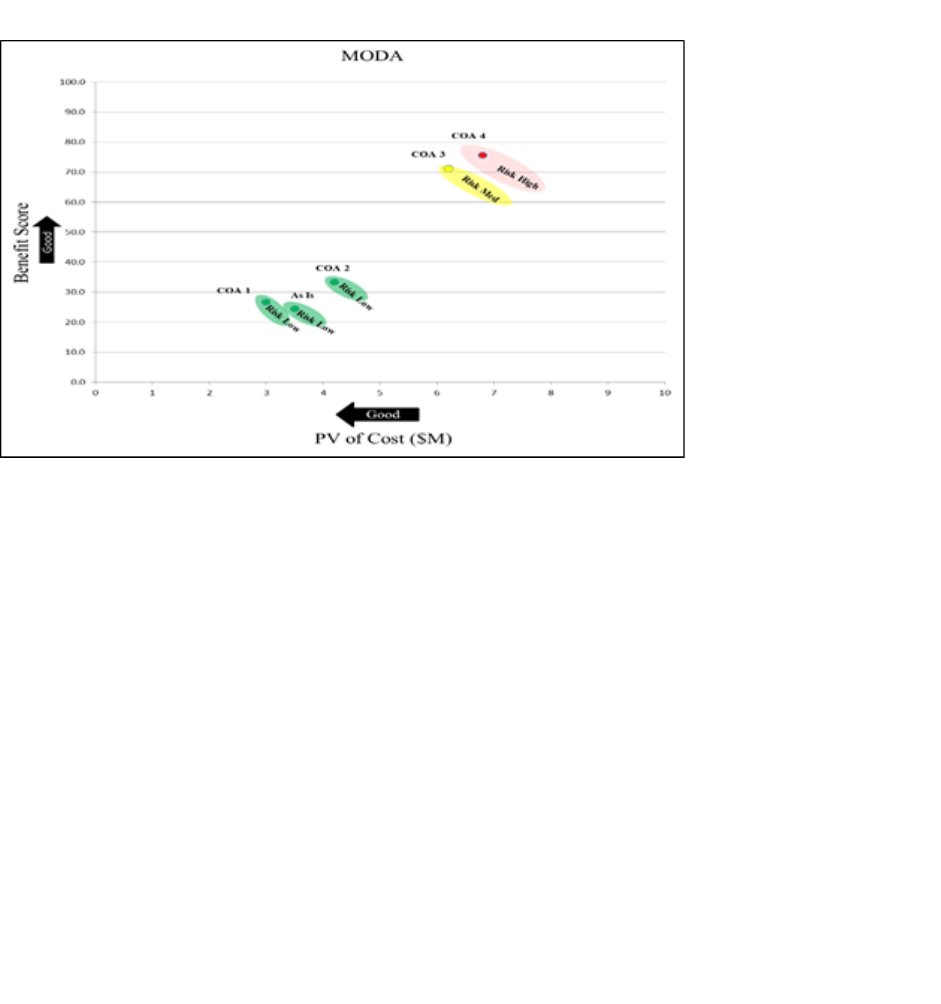

8.4. Displaying the Results – WUS and MODA (Cost Capability Analysis). ................ 74

Figure 8.7. Risk Cube. ................................................................................................................ 75

Figure 8.8. COA Weighting. ...................................................................................................... 75

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 5

Figure 8.9. WUS Display (Example 1). ..................................................................................... 76

Figure 8.10. WUS Display (Example 2). ..................................................................................... 76

Figure 8.11. MODA. .................................................................................................................... 78

Chapter 9—DATA SELECTION, COLLECTION AND ASSESSMENT 79

9.1. Quality Data Collection. .......................................................................................... 79

9.2. Data Selection. ......................................................................................................... 79

Table 9.1. Milestone Data Maturity. ......................................................................................... 79

Table 9.2. Data Quality Tiers. ................................................................................................... 81

Table 9.3. Potential PS-BCA Data Sources. ............................................................................. 81

Table 9.4. Example – Data Requirements and Selection. ......................................................... 83

Table 9.5. Data Plan Considerations. ........................................................................................ 84

Chapter 10—SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION 88

10.1. Sensitivity Analysis Defined.................................................................................... 88

10.2. Risk and Uncertainty. .............................................................................................. 88

10.3. Variables. ................................................................................................................. 88

10.4. Steps in Conducting a Sensitivity Analysis. ............................................................ 88

10.5. Examples for Using Sensitivity Analysis. ............................................................... 89

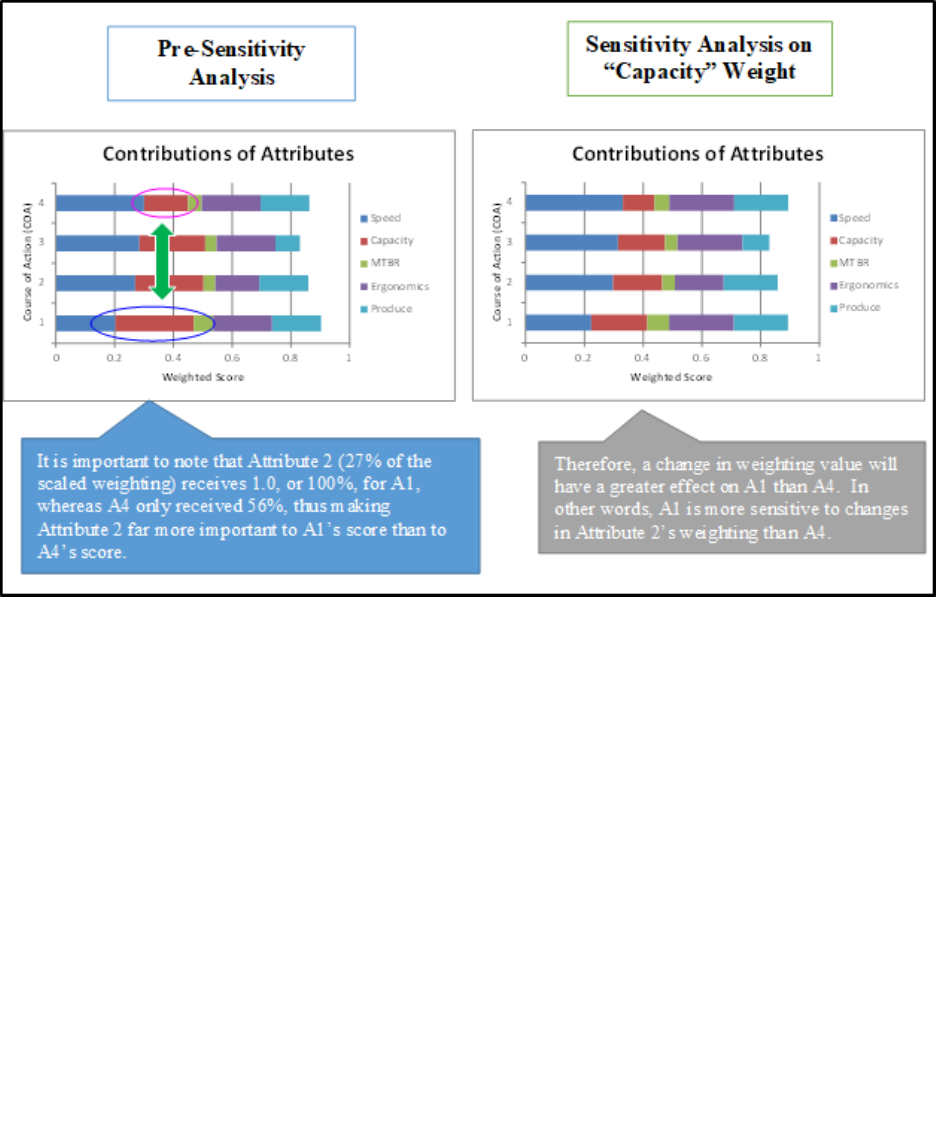

10.6. Applying Sensitivity Analysis to Weighting and Scoring of Benefits. .................... 90

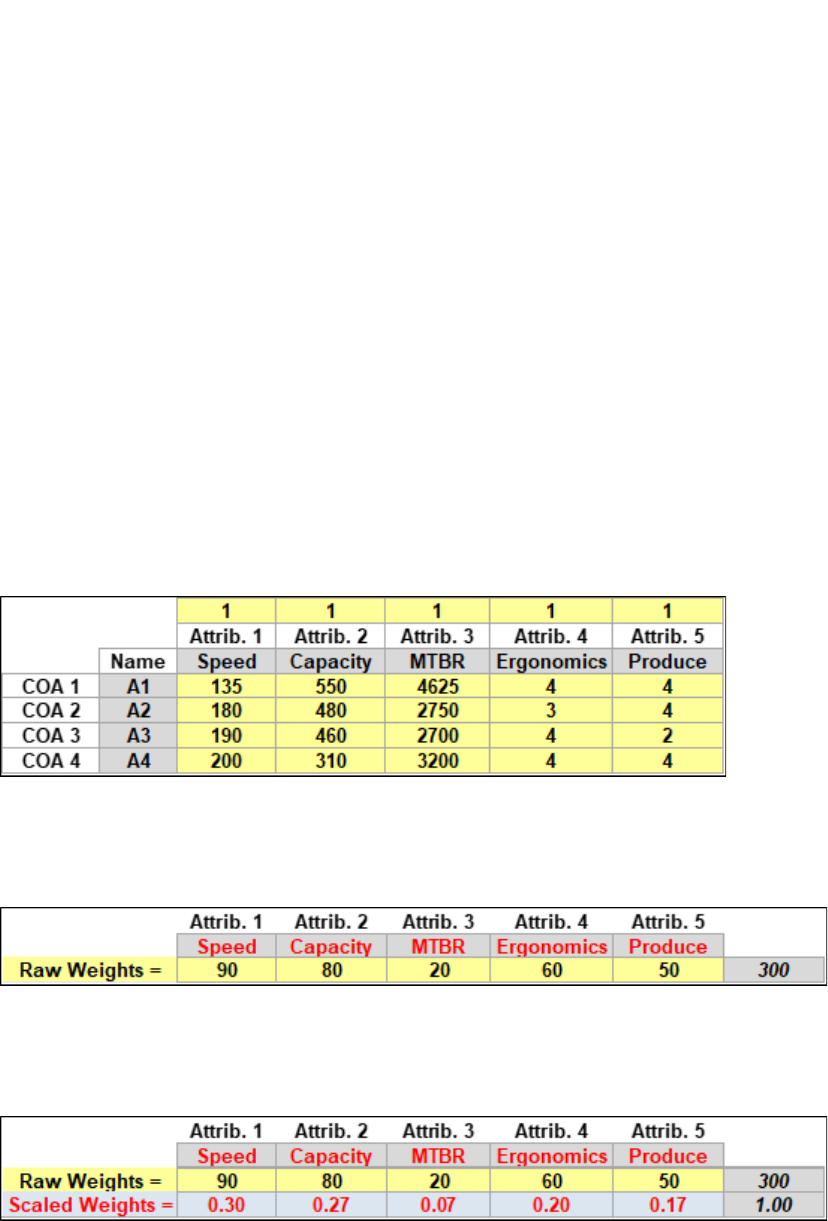

Table 10.1. COAs and Attributes. ............................................................................................... 90

Table 10.2. Raw Weights. ........................................................................................................... 90

Table 10.3. Scaled Weights. ....................................................................................................... 90

Table 10.4. COAs, Attributes, Raw and Scaled Weights............................................................ 91

Figure 10.1. COAs Weighted Benefit Scores vs Their Cost. ....................................................... 91

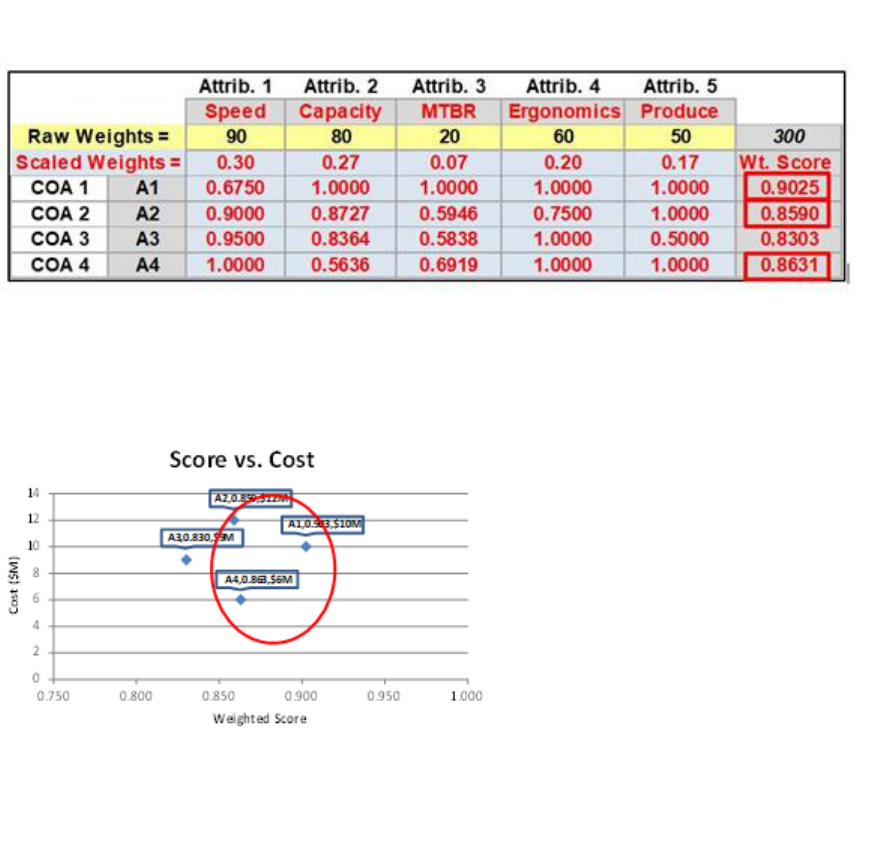

Table 10.5. Sensitivity Analysis Adjustment. ............................................................................. 92

Figure 10.2. COAs Weighted Benefit Scores vs Their Cost after Weight Changes. ................... 92

Figure 10.3. Sensitivity Analysis Displays. ................................................................................. 93

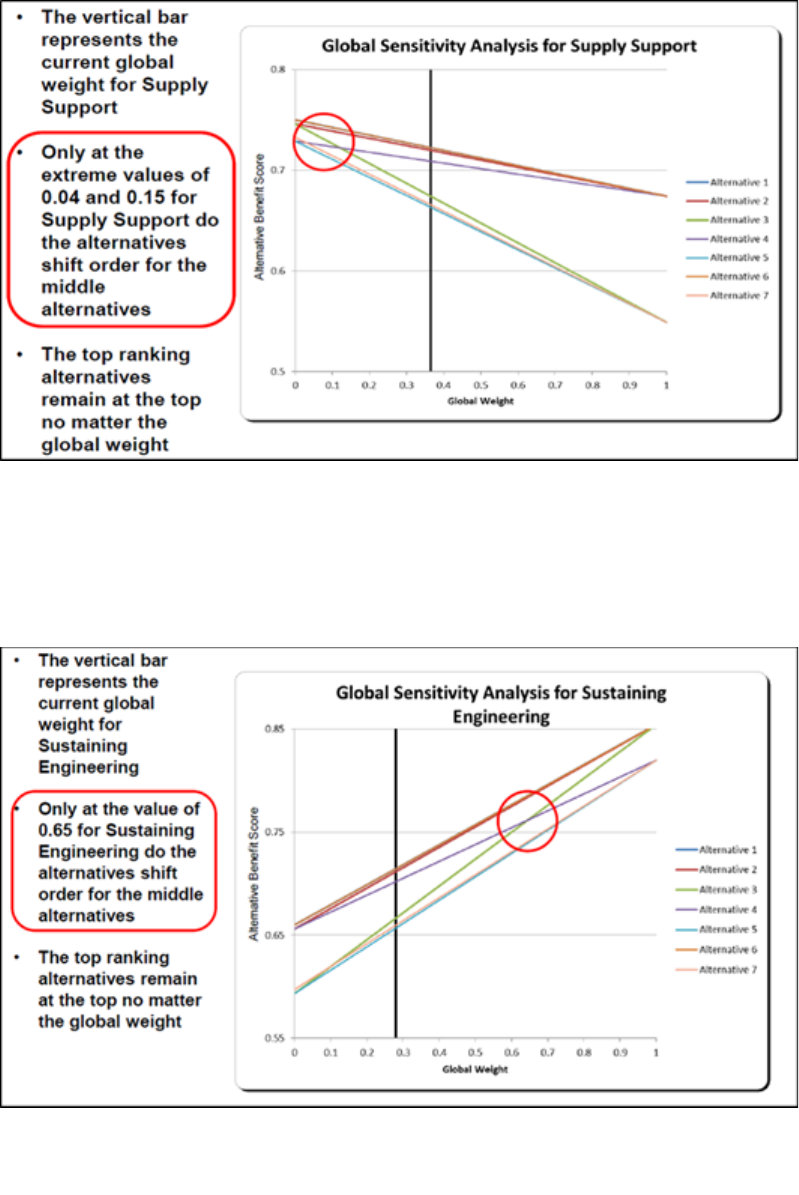

10.7. Applying Sensitivity Analysis to Benefits. .............................................................. 93

10.8. Shifting Attribute Scores. ........................................................................................ 93

Figure 10.4. Global Sensitivity Analysis for Supply Support. ..................................................... 94

Figure 10.5. Global Sensitivity Analysis for Sustaining Engineering. ......................................... 94

10.9. Tipping Point. .......................................................................................................... 95

6 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

Chapter 11—FINDINGS, RECOMMENDATION, APPROVAL AND

IMPLEMENTATION FOR THE FINAL PRODUCT SUPPORT

BUSINESS CASE ANALYSIS REPORT 96

11.1. PS-BCA Report. ....................................................................................................... 96

Table 11.1. PS-BCA Report Process. ......................................................................................... 96

11.2. PS-BCA Findings. ................................................................................................... 96

Table 11.2. Findings Summary. .................................................................................................. 96

Table 11.3. Cost to the Program Output Example. ..................................................................... 99

Table 11.4. Alternative Comparisons. ........................................................................................ 99

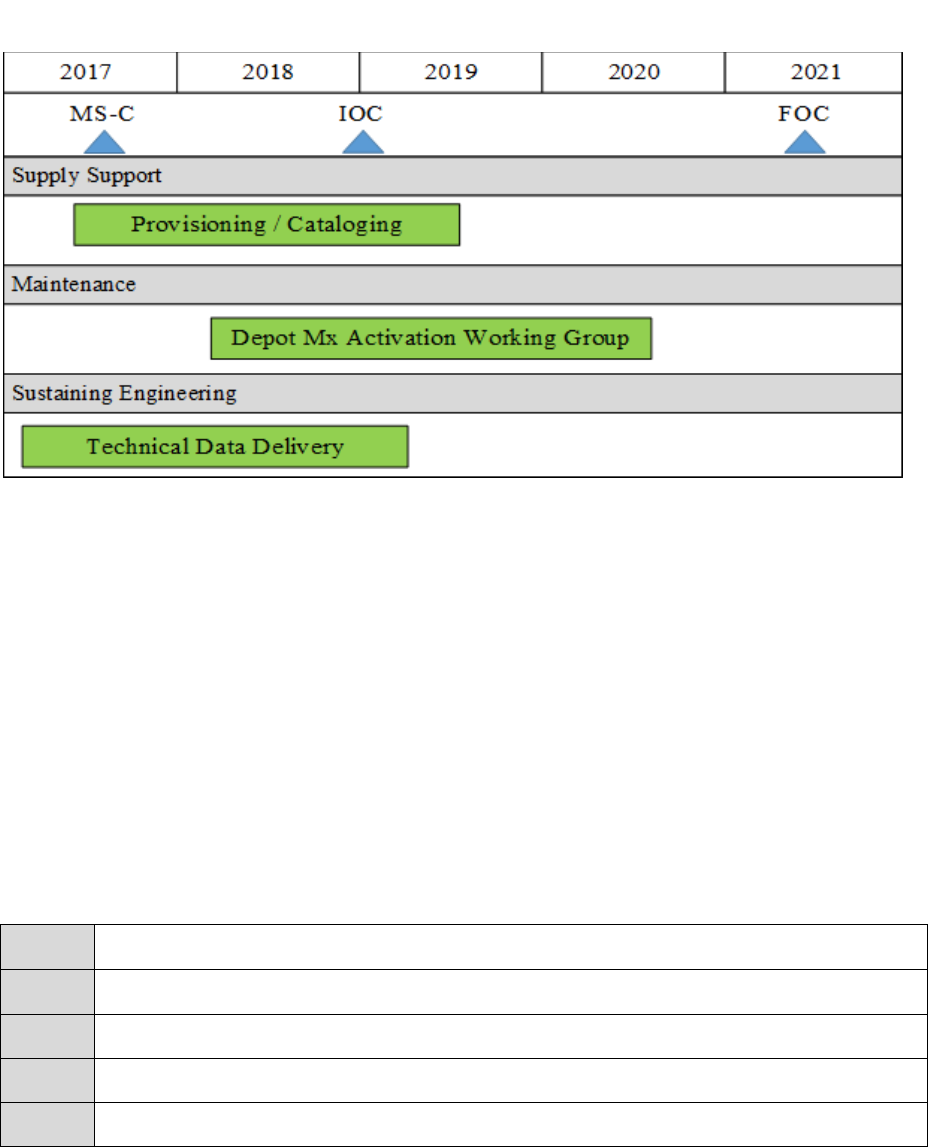

Figure 11.1. COA Example for Transition Plans. ........................................................................ 100

Table 11.5. Outline for PS-BCA Out-Brief. ............................................................................... 100

Table 11.6. PS-BCA Final Report Outline. ................................................................................ 102

Table 11.7. Implementation Plan Outline. .................................................................................. 103

Attachment 1—GLOSSARY OF REFERENCES AND SUPPORTING INFORMATION 105

Attachment 2—LEGACY PROGRAM PRODUCT SUPPORT BUSINESS CASE

ANALYSIS SUFFICIENCY MEMORANDUM 112

Attachment 3—PROCESS NARRATIVE 113

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 7

Chapter 1

OVERVIEW

1.1. Product Support Business Case Analysis (PS-BCA) Pamphlet Overview. Product

Support Business Case Analysis (PS-BCA) Pamphlet. This is designed to assist the PS-BCA Team

in developing comprehensive Product Support (PS) strategies that achieve the optimal balance

between warfighter capabilities and affordability (i.e., best-value). The pamphlet covers key areas

that the PS-BCA Team needs to consider when developing an effective PS-BCA. The pamphlet

provides a standardized format, assists in developing and evaluating courses of action (COAs),

recommends useful decision support methodologies that enhance defendable decision making

processes, and provides guidance on developing the PS-BCA report. Additionally, the pamphlet

provides examples and best practices, identifies existing laws, integrates Department of Defense

(DoD) guidance located in the DoD Product Support BCA Guidebook (April 2011), and

supplements existing Air Force Manuals (AFMANs) such as AFMAN 65-506, Economic Analysis

(September 2019). The focus of the pamphlet is on Major Defense Acquisition Programs

(MDAPs), however, the techniques provided can also be applied to any program using any

acquisition pathway.

1.2. Business Case Analysis (BCA). A Business Case Analysis (BCA) is a decision support

document that identifies COAs and then presents convincing business (both financial and non-

financial) impacts, risks, sensitivities, and technical arguments for selecting a specific COA that

will achieve desired objectives. A BCA provides a fair and objective study that leads to a decision,

not justify a decision after the fact. Specifically, a BCA is a comparative analysis product that fits

under the umbrella of the economic analysis approach. All BCAs are required to follow the

guidance in AFI 65-501, Economic Analysis, and AFMAN 65-506.

AFMAN 65-506 provides more detailed information on the elements that must be addressed as

part of the economic analysis approach whereas this pamphlet provides the standardized format

for completing BCAs as well as lessons learned and best practices.

1.2.1. Introduction. Defines what the business case is about (subject), why (purpose) it is

necessary, what the objectives are, and who the decision maker is for the BCA.

1.2.2. Problem Statement. Concisely defines the problem, requirement or opportunity being

analyzed. What problem is trying to be solved and is it realistic? What is the scope of the

analysis? The problem statement helps define the analysis framework.

1.2.3. Methods and Parameters. States the analysis methods and rationale that will fix the

boundaries of the business case (the costs and benefits examined over what time period). This

section also outlines the rules for deciding what belongs in the analysis and what does not.

Facts, ground rules, and assumptions are parameters that must be explicitly stated on what is

believed to be true of a current or identify future state of affairs. Further details regarding each

of these parameters can be found in AFMAN 65-506, Section 2.4.

1.2.4. Business and Operational Impacts. Documents costs, benefits and non-monetary

benefits impacting business and operational results for each COA.

1.2.5. Risk Analysis. Evaluates the probability of negative events occurring in each COA and

their impact on desired objectives.

8 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

1.2.6. Sensitivity Analysis. Demonstrates how the BCA results are affected by changes in key

variables such as assumptions, weightings, and key data drivers in the analysis. AFMAN 65-

506 requires a sensitivity analysis to test the effect that major assumptions have on analysis

results.

1.2.7. Recommendation and Implementation Plan. Recommends a preferred COA and the

action plan required to achieve desired objectives.

1.2.7.1. Per the DoD Product Support BCA Guidebook and AFMAN 65-506, a BCA does

not replace the judgment of the decision maker, but rather provides an analytic and uniform

foundation that allows decision makers to make informed decisions. A BCA can vary in

size and scope, is developed in an unbiased manner, and is not constructed to justify a

preordained decision. A key element in constructing an effective BCA is acquiring

sufficient data from reliable sources and then analyzing the information utilizing a

consistent methodology. With the same data and comprehensive documentation, readers

not familiar with the analysis should be able to replicate the analysis and arrive at the same

conclusions.

1.3. Product Support Business Case Analysis (PS-BCA).

1.3.1. Decision Support Document. A PS-BCA is a decision support document that assists

Product Support Managers (PSMs) in developing COAs for product support strategies using

the best value approach, which incorporates Integrated Product Support (IPS) elements.

Attachment 1 defines best value per the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR).

1.3.2. PS-BCA Process. The PS-BCA is an iterative process that incorporates organizational

or programmatic changes. PS-BCAs can be used for a number of purposes to include the

following:

Determine whether or not to change Product Support Strategy (PSS)

Determine whether or not to invest in product support

Determine whether or not to select among COAs

Validate proposed scope, schedule, or budget changes during the course of the program

1.3.3. Product Support Decisions. The PS-BCA supports major product support decisions,

especially those that result in new or changed resource requirements. Program Managers

(PMs) are responsible for deploying the PSS and monitoring its performance according to the

Life Cycle Sustainment Plan (LCSP). While the PS-BCA assists in the leaders’ decision

making process, it does not supersede or overturn other statutory requirements (e.g., 10 USC

§2464, Core Logistics Capabilities, 10 USC §2466, Limitations on the performance of depot-

level maintenance of materiel.

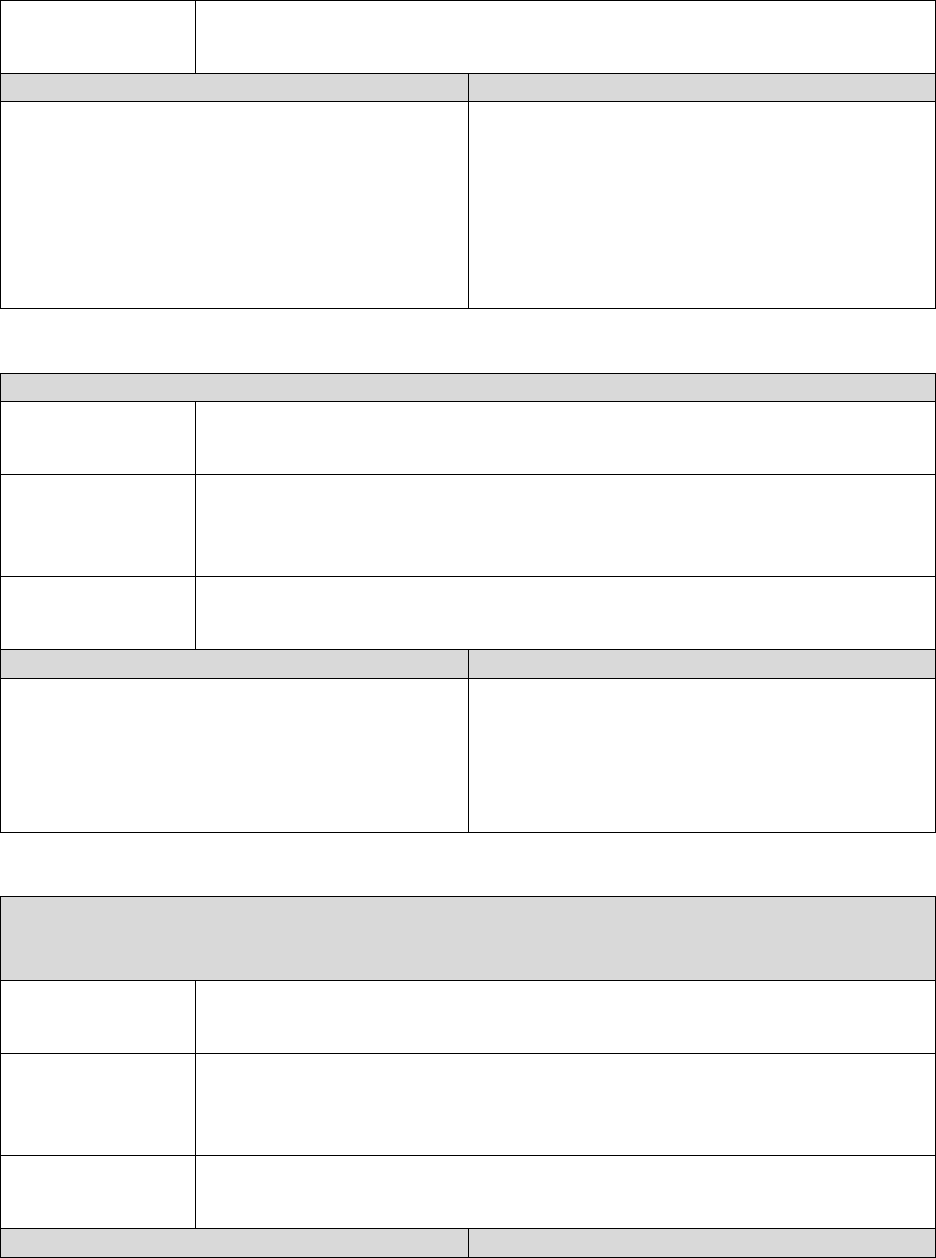

1.3.4. Major Elements. The PS-BCA has three major elements: purpose, process components,

and quality foundation (see Figure 1.1 below) that work together to ensure the PS-BCA targets

the relevant subject matter, analyzes and reports the results, and integrates into the

organization’s mission and vision.

1.3.4.1. Purpose. Identifies the problem statement, objectives, metrics, desired outcomes,

and requirements. The purpose annotates what problem the PS-BCA is attempting to solve

and how to measure success.

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 9

1.3.4.2. Process Components. Subsections of the PS-BCA that directly execute and report

on analytical actions. PSMs should refer to the DoD PS-BCA Guidebook and must follow

guidance in AFMAN 65-506 to determine what to include in the components section. Of

particular note, within the implementation plan, a PS-BCA should include predetermined

off-ramps. These off-ramps are actions to be taken when the desired objectives are not

being achieved for the selected COA.

1.3.4.3. Quality Foundation. Directly affects the quality and completeness of the analysis.

This section consists of research, due diligence (verifying the accuracy of the information),

governance (provides oversight), documentation, and data management.

Figure 1.1. Product Support BCA Elements.

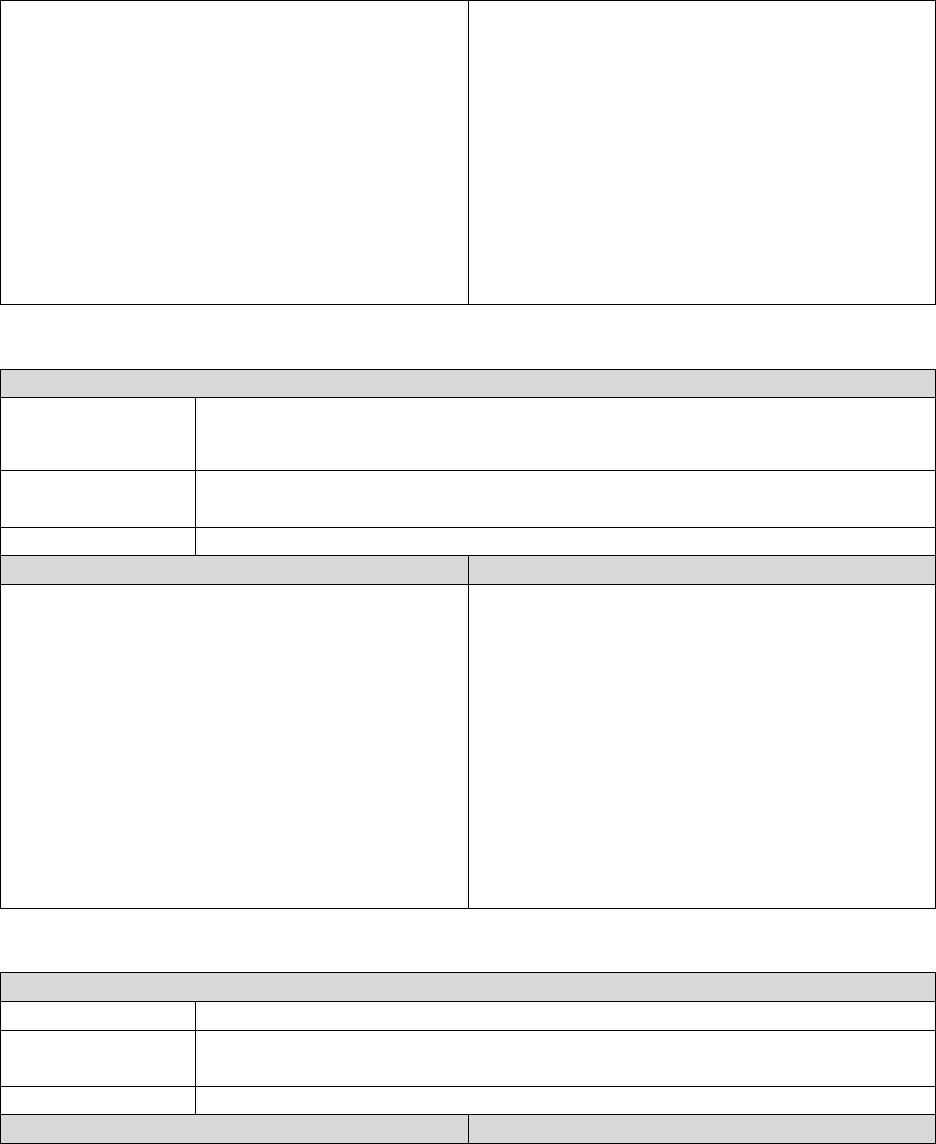

1.3.5. Integrated Product Support (IPS) Elements. The PS-BCA is used to analyze a program’s

PSS and are represented by the 12 IPS elements, as identified in Appendix A of the DoD

Product Support Manager Guidebook. Each program is unique and the IPS elements to be

analyzed are dependent upon the specific sustainment requirements of the weapon system.

Rationale should be provided for each of the 12 IPS elements whether utilized or not within

the PS-BCA. The IPS elements categorize major support areas and provide standardized

definitions. One recommended approach in addressing the 12 IPS elements is shown in Figure

1.2 The 12 IPS elements are 1) Product Support Management; 2) Design Interface; 3)

Sustaining Engineering (SE); 4) Supply Support; 5) Maintenance Planning and Management;

6) Packaging, Handling; Storage & Transportation; 7) Technical Data; 8) Support Equipment;

9) Training and Training Support; 10) Manpower and Personnel; 11) Facilities and

Infrastructure; and 12) Computer Resources. Of the 12 IPS elements, those most often

compared between COAs within a PS-BCA are the following:

1.3.5.1. Product Support Management. Focuses on integrating all sources of product

support, public and private, within the scope of a product support arrangement.

1.3.5.2. Sustaining Engineering. Examines the technical tasks (i.e., engineering and

logistics investigations and analysis) required to ensure continued operation and

10 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

maintenance of a system. See AFI 63-101/20-101, Chapter 5, “Systems Engineering,” for

guidance on the engineering requirements that PMs will address to ensure the continued

operation and maintenance of a system.

1.3.5.3. Supply Support. Focuses on procuring, producing, and delivering products and

services to customers as well as the flow of funds.

1.3.5.4. Maintenance Planning and Management. Focuses on the maintenance of parts,

assemblies, sub-assemblies, and end items. This might include manufacturing parts,

making modifications, testing, and reclamation, as needed.

Figure 1.2. Four Major Areas for 12 IPS Elements.

1.3.5.5. The PS-BCA should follow the cost estimating guidance outlined in the DoD

“Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) Operating and Support Cost

Estimating Guide 2014” and be structured according to the IPS elements and the CAPE

Cost elements.

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 11

1.3.5.5.1. Best Practice. The Program Management Office (PMO) should also plan to

acquire government data rights and delivery of technical data as required by 10 USC

§2320, Rights in Technical Data. Prior to Milestone (MS)-B, the PMO should develop

a PS-BCA data collection plan that identifies the data requirements and data system

access requirements for the analysis. Information such as demand history for supply

chain (which parts are replaced or repaired and how often), maintenance repair

procedures/process, and product support performance metrics (e.g., Customer Wait

Time (CWT), engineering request response time) are types of information that can be

captured. In addition, cost reporting and priced bill of materials with the appropriate

amount of fidelity should be obtained if available.

1.4. When to Conduct a PS-BCA. The PS-BCA is a statutory requirement for all major weapon

systems based on 10 USC §2337, Life-Cycle Management and Product Support. Air Force

Instruction (AFI) 63-101/20-101 further identifies PS-BCA requirements as mandatory for

Acquisition Category (ACAT) I and ACAT II programs and at the discretion of the Milestone

Decision Authority (MDA) for ACAT III programs.

1.4.1. MDA Discretion. For existing platforms/systems, the MDA also has the discretion to

initiate a PS-BCA. All modification programs that are classified as ACAT I or ACAT II

programs also require a PS-BCA. PS-BCAs for modifications to ACAT III programs are at

the discretion of the MDA. However, once modifications are in the sustainment phase,

consolidate the modification PS-BCA into the system/platform level PS-BCA. The PS-BCA

should begin as early as pre-MS-A or initial entry into the acquisition life cycle.

1.4.2. Objectives and Approach. PS-BCA objectives and approach are determined by the point

at which they are accomplished within the program’s life cycle.

1.4.2.1. Prior to MS-A and MS-B. Department of Defense Instruction (DoDI) 5000.02

states a BCA will be included as an annex to the LCSP. While there are challenges to

completing a BCA early in the acquisition life cycle due to the lack of data and system

information available, DoDI 5000.02 directs a BCA to be accomplished in support of the

MS-A decision. This BCA includes “the assumptions, constraints, and analysis used to

develop the product support strategy documented in the LCSP.” This comprises the BCA

scope and methodology, laying the groundwork for product support management and

integration, supply chain management, and maintenance planning. Defining these areas

early provides the framework to assess options for potential future COAs and solidifies the

methodology for conducting the PS-BCA. PS-BCAs prior to MS-A and B may be limited

in depth and detail when compared to a PS-BCA at MS-C and later.

1.4.2.2. Between MS-B and MS-C. A PS-BCA that fully examines the system’s PSS

should be completed prior to MS-C using a best value approach for PSS development that

addresses each IPS element. A “revalidation” of previous PS-BCAs is statutorily required

if five years or more will span between milestones. The revalidation should confirm the

strategy is progressing and update the data and analytical results.

1.4.2.3. Post MS-C. A PS-BCA requires revalidating/updating prior to any proposed

change in the PSS or at a minimum every five years. Follow the decision tree in section

1.3.1 to determine if a program should accomplish a PS-BCA if a PS-BCA has not been

accomplished previously. The same level of analysis may not be required in all cases for

a Post MS-C PS-BCA. If the situation allows, a PS-BCA may only require “revalidation”

12 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

of the previous analysis, by confirming the strategy is progressing and updating the data

and analytical results. Note: Programs that are post MS-C prior to the enactment of 10

USC §2337, Life-Cycle Management and Product Support, did not have the legislated

requirement to develop a PS-BCA prior to

MS- C. As a result, they are not required to perform a PS-BCA as part of their 5-year

revalidation. A PS-BCA is still required when determining a change to the PSS.

1.4.2.4. The level of detail in a PS-BCA differs according to where the program is in the

life cycle, as shown in Figure 1.3:

Figure 1.3. PS-BCA Schedule Throughout the Life Cycle.

1.4.2.5. Given the product support COAs may evolve as the life cycle progresses, there is

no standard set of support COAs for a PS-BCA. Best value product support approach may

include some mix of organic (e.g., government) and contractor support, as well as Public-

Private Partnerships (PPP). DoD Public-Private Partnering (PPP) for Product Support

Guidebook provides greater fidelity on PPP. The potential COAs should materialize

through the execution of the PS-BCA process. The merits of various sourcing and

partnering options should be identified as system support capabilities are analyzed across

the IPS elements and various support COAs are weighted against desired support

requirements and objectives.

1.4.2.6. The PS-BCA decision tree in section 1.4.3.1 is designed to assist the PSM in

determining what actions are required with respect to either developing a PS-BCA or

revalidating/updating the previously completed PS-BCA. At each step within the process

the narrative addresses the requirements and expected objectives. Revalidating/updating

the PS-BCA does not mean completely redoing the PS-BCA every five years. As the PSM

works through each step, the decision tree process assists in determining the requirements

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 13

(i.e., Memorandum for Record (MFR) to document findings or update previous PS-BCA)

and outputs.

1.4.3. PS-BCA Decision Tree

1.4.3.1. Step 1: PS-BCA been previously completed for THIS program?

Figure 1.4. Step #1 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree.

Table 1.1. Step #1 Decision Tree Process Flow.

Step

What Happens

❶ PS-BCA BEEN PREVISOULY COMPLETED FOR THIS PROGRAM?

Establish if a PS-BCA was previously completed. If a PS-BCA was completed,

consider this effort an update. Utilize the previously completed PS-BCA as the

starting point.

If Yes (Previous PS-BCA completed)

If No (No previous PS-BCA)

Continue to “Step (2) 5-year

Revalidation or Strategy Change”

Continue to “(A) PMO Considering PSS

Change”

A

Determine if the PMO is considering a change to the existing Product Support

Strategy

If Yes (Change to PSS Change)

If No (No change to PSS)

14 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

Step

What Happens

Continue to “(C) Complete PS-BCA

Continue to “(B) Program has received

MS-C approval from MDA?

B

Determine if program has received MS-C approval?

If Yes (Program has received MS-C from

MDA?)

If No (Program does not have MS-C

approval from MDA)

Continue to “(D) Is current PSS

affordable & effective?

Continue to “(C) Complete PS-BCA

C

Complete PS-BCA

Complete a PS-BCA in accordance with the following guidance:

AF PS-BCA Pamphlet

AFI 65-501

AFMAN 65-610

DoD PS-BCA Guidebook

Continue to Activity (F)

D

Establish if current PSS is within expected costs and metrics are achieving warfighter

requirements.

If Yes (PSS achieving goals)

If No (PSS not achieving goals)

Continue to “(E) MFR to MDA /

Document in LCSP”

Return to Activity “(C) and complete PS-

BCA”

E

MFR to MDA / Document in LCSP

Prepare a memo for the record that documents the results of the analysis performed.

Memo for record includes rationale for the assessment of affordability and

effectiveness of the program. This documentation should be included in an annex

within the LCSP. MDA documentation and updates should be annexed within LCSP.

Attachment 2 provides a sample Legacy Program PS-BCA Sufficiency Memo.

Process ends after this step.

F

Develop Recommendation

Summarize the findings in a clear and concise manner that explains the recommended

solution and why it is recommended. Make reference to the other COAs and how

they compare to the recommended COA in costs, benefits, and risks. The

recommendation should be specific, comprehensive, measurable, consistent, accurate,

timely, unbiased, and achievable.

Continue to activity (G)

G

Program MDA Decision Point

Present the recommendation to the MDA for approval. The MDA should document

the rationale for the PS-BCA final decision. This final decision documentation serves

as an archive, and combined with the PS-BCA, provides the baseline for the next

iteration of the PS-BCA. The MDA decision provides closure to the process and

initiates the transition to the selected PSS. MDA documentation (MFR to MDA) and

updates should be annexed within LCSP.

Process ends after this step.

1.4.3.2. Step 2: 5-year Revalidation or Strategy Change

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 15

Figure 1.5. Step #2 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree.

Table 1.2. Step #2 Decision Tree Process Flow.

Step

What Happens

❷ 5-YEAR REVALIDATION or STRATEGY CHANGE?

If a PS-BCA was completed previously, determine the reason for updating the PS-

BCA. There are generally two reasons to update a PS-BCA: 1) five years have

lapsed since the most recent PS-BCA was accomplished or 2) there is a change in the

PSS.

If 5-Year Revalidation

If a Strategy Change

Continue to “Step 3) Is previous PS-

BCA approved & implementation on

track?”

Continue to “(H) Perform assessment;

outcome change?”

16 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

H

Perform assessment; outcome change?

Determine how changing the PSS impacts the previous PS-BCA, by determining

what changed and then assess how the changes impact costs, benefits, and risks.

Next, assess if the changes would lead to a different recommendation. This can be

done in a variety of ways, one of which is to determine how much the previous

results would have to change in order for the recommendation to change. Then

determine if the current changes fall within those bounds. This is equivalent to

performing a sensitivity analysis on the prior PS-BCA.

If Yes (Change in outcome)

If No (No change in outcome)

Continue to “(I) Update Previous PS-

BCA”

Continue to “(E) MFR to MDA /

Document in LCSP”

I

Update Previous PS-BCA

Update the previous PS-BCA using the most current data available. Since the

outcome has changed, this should require reviewing all areas within the PS-BCA

(i.e., costs, benefits, and risks). Incorporate any new information (e.g., extension of

the service life since the last PS-BCA) that has come available since the previous PS-

BCA was completed and update ground rules and assumptions as appropriate.

Continue to activity (F)

F

Develop Recommendation

Summarize the findings in a clear and concise manner that explains the

recommended solution and why it is recommended. Make reference to the other

COAs and how they compare to the recommended COA in costs, benefits, and risks.

The recommendation should be specific, comprehensive, measurable, consistent,

accurate, timely, unbiased, and achievable.

Continue to activity (G)

G

Program MDA Decision Point

Present the recommendation to the MDA for approval. The MDA should document

the rationale for the PS-BCA final decision. This final decision documentation

serves as an archive, and combined with the PS-BCA, provides the baseline for the

next iteration of the PS-BCA. The MDA decision provides closure to the process

and initiates the transition to the selected PSS. MDA documentation (MFR to MDA)

and updates should be annexed within LCSP.

Process ends after this step.

E

MFR to MDA / Document in LCSP

Prepare a memo for the record that documents the results of the analysis performed.

Memo for record includes rationale for the assessment of affordability and

effectiveness of the program. This documentation should be included in an annex

within the LCSP. MDA documentation and updates should be annexed within LCSP.

Attachment 2 provides a sample Legacy Program PS-BCA Sufficiency Memo.

Process ends after this step.

1.4.3.3. Step 3: Was the Recommendation Implemented?

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 17

Figure 1.6. Step #3 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree.

Table 1.3. Step #3 Decision Tree Process Flow.

Step

What Happens

❸ WAS THE RECOMMENDTION IMPLEMENTED?

If five years has passed since the latest PS-BCA was completed, an update is

required. Updating the PS-BCA does not mean the PS-BCA should be completely

redone. Decide first if the PS-BCA recommendation was implemented or is being

implemented.

If Yes (Recommendation was

implemented)

If No (Recommendation not

implemented)

Continue to “Step 4) Is the Solution

Meeting Program Objectives?”

Continue to “(J) Identify & document

changes and causes for non-

implementation”

18 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

Step

What Happens

J

Identify & document changes and causes for non-implementation

Assess and document the reasons why the recommendation was not implemented.

Those reasons could include lack of funding, changes in the political environment,

programmatic changes, inability to obtain required technical data, etc. If the

implementation date slipped, update the implementation plan accordingly and

document the reason for the slippage. Once the reason for non-implementation is

identified and documented, an assessment should be performed to determine if the

recommendation is still valid. If the recommendation is no longer valid, update the

previous PS-BCA in order to determine the appropriate PSS based on current ground

rules, assumptions, program environment and current data.

Continue to activity (I)

I

Update Previous PS-BCA

Update the previous PS-BCA using the most current data available. Since the

outcome has changed, this should require reviewing all areas within the PS-BCA

(i.e., costs, benefits, and risks). Incorporate any new information (e.g., extension of

the service life since the last PS-BCA) that has come available since the previous PS-

BCA was completed and update ground rules and assumptions as appropriate.

Continue to activity (F)

F

Develop Recommendation

Summarize the findings in a clear and concise manner that explains the

recommended solution and why it is recommended. Make reference to the other

COAs and how they compare to the recommended COA in costs, benefits, and risks.

The recommendation should be specific, comprehensive, measurable, consistent,

accurate, timely, unbiased, and achievable.

Continue to activity (G)

G

Program MDA Decision Point

Present the recommendation to the MDA for approval. The MDA should document

the rationale for the PS-BCA final decision. This final decision documentation

serves as an archive, and combined with the PS-BCA, provides the baseline for the

next iteration of the PS-BCA. The MDA decision provides closure to the process

and initiates the transition to the selected PSS. MDA documentation (MFR to MDA)

and updates should be annexed within LCSP.

Process ends after this step.

1.4.3.4. Step 4: Is the Solution Meeting Program Objectives?

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 19

Figure 1.7. Step #4 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree.

Table 1.4. Step #4 Decision Tree Process Flow.

Step

What Happens

❹ IS SOLUTION MEETING OBJECTIVE?

Assuming the recommendation was implemented, determine if the solution is meeting

the objectives as stated in the PS-BCA.

If Yes (Solution is meeting objective)

If No (Solution is not meeting objective)

Continue to “Step 5) Major Change in

Program Ground Rules and Assumptions

(GR&A) or Program Environment?”

Continue to “(J) Identify & document

changes and causes for non-performance”

20 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

Step

What Happens

J

Identify & document changes and causes for non-performance

Identify and document the reasons why the solution is not meeting the objectives set

forth in the PS-BCA. An example could be that a single work stream is not

performing as projected (e.g., maintenance organizations not meeting flow days,

supply organizations inability to fill customer requisitions in a timely manner or cost

increases have caused budgetary impacts to the program).

Continue to Activity (I)

I

Update Previous PS-BCA

Update the previous PS-BCA using the most current data available. Since the

outcome has changed, this should require reviewing all areas within the PS-BCA (i.e.,

costs, benefits, and risks). Incorporate any new information (e.g., extension of the

service life since the last PS-BCA) that has come available since the previous PS-

BCA was completed and update ground rules and assumptions as appropriate.

Continue to activity (F)

F

Develop Recommendation

Summarize the findings in a clear and concise manner that explains the recommended

solution and why it is recommended. Make reference to the other COAs and how

they compare to the recommended COA in costs, benefits, and risks. The

recommendation should be specific, comprehensive, measurable, consistent, accurate,

timely, unbiased, and achievable.

Continue to activity (G)

G

Program MDA Decision Point

Present the recommendation to the MDA for approval. The MDA should document

the rationale for the PS-BCA final decision. This final decision documentation serves

as an archive, and combined with the PS-BCA, provides the baseline for the next

iteration of the PS-BCA. The MDA decision provides closure to the process and

initiates the transition to the selected PSS. MDA documentation (MFR to MDA) and

updates should be annexed within LCSP.

Process ends after this step.

1.4.3.5. Step 5: Major Change in Program GR&A or Program Environment?

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 21

Figure 1.8. Step #5 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree.

Table 1.5. Step #5 Decision Tree Process Flow.

Step

What Happens

❺ MAJOR CHANGE IN PROGRAM GR&A / PROGRAM ENVIRONMENT?

Assuming the solution is meeting the objective, assess if the PS-BCA GR&As and/or

operating environment have changed.

If Yes (GR&A or environment

changed)

If No (GR&A or environment not

changed)

Continue to “(K) Update GR&A”

Continue to “Step 6) Review Input; More

Current Data Available?”

22 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

Step

What Happens

❺ MAJOR CHANGE IN PROGRAM GR&A / PROGRAM ENVIRONMENT?

K

Update GR&A

To determine how changes in the GR&A and/or program environment impact the

PS-BCA, review the existing PS-BCA GR&A. The Integrated Project Team (IPT)

should document any changes to the GR&A and/or program environment. If new

information is available that would drive additional GR&As that were not previously

captured, those would be included in the update.

Continue to activity (L)

L

Perform assessment; outcome change?

Identify if and how those changes/additions in the GR&A and/or program

environment affect costs, benefits, and risks. Determine if the recommendation

would change based on the updated information. There are several methods that can

be used, however, the method used and results should be documented. No one

method is prescribed, but the method and logic used should be thoroughly

documented to the degree that it is repeatable.

If Yes (Change in outcome)

If No (No change in outcome)

Continue to “(I) Update PS-BCA”

Continue to “(E) MFR to MDA”

I

Update Previous PS-BCA

Update the PS-BCA to reflect the revised GR&A and/or program environment.

Update the previous PS-BCA using the most current data available. Since the

outcome has changed, this should require reviewing all areas within the PS-BCA

(i.e., costs, benefits, and risks). Incorporate any new information (e.g., extension of

the service life since the last PS-BCA) that has come available since the previous PS-

BCA was completed and update ground rules and assumptions as appropriate.

Continue to activity (F)

F

Develop Recommendation

Summarize the findings in a clear and concise manner that explains the

recommended solution and why it is recommended. Make reference to the other

COAs and how they compare to the recommended COA in costs, benefits, and risks.

The recommendation should be specific, comprehensive, measurable, consistent,

accurate, timely, unbiased, and achievable.

Continue to activity (G)

G

Program MDA Decision Point

Present the recommendation to the MDA for approval. The MDA should document

the rationale for the PS-BCA final decision. This final decision documentation

serves as an archive, and combined with the PS-BCA, provides the baseline for the

next iteration of the PS-BCA. The MDA decision provides closure to the process

and initiates the transition to the selected PSS. MDA documentation (MFR to MDA)

and updates should be annexed within LCSP.

Process ends after this step.

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 23

Step

What Happens

❺ MAJOR CHANGE IN PROGRAM GR&A / PROGRAM ENVIRONMENT?

E

MFR to MDA / Document in LCSP

Prepare a memo for the record that documents the results of the analysis performed.

Memo for record includes rationale for the assessment of affordability and

effectiveness of the program. This documentation should be included in an annex

within the LCSP. MDA documentation and updates should be annexed within LCSP.

Attachment 2 provides a sample Legacy Program PS-BCA Sufficiency Memo.

Process ends after this step.

1.4.3.6. Step 6: Review Input; More Current Data Available?

Figure 1.9. Step #6 of the PS-BCA Decision Tree.

24 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

Table 1.6. Step #6 Decision Tree Process Flow.

Step

What Happens

❻ REVIEW INPUT; MORE CURRENT DATA AVAILABLE?

Assuming there are no major changes in program GR&A and/or program

environment, review the data used within the PS-BCA and update to reflect the most

current data available.

If Yes (More current data available)

If No (Data is current)

Continue to “(M) Outcome changes?”

Continue to “(E) MFR to MDA”

M

Outcome changes?

Identify if and how the more current data will affect costs, benefits, and risks.

Determine if the recommendation would change based on the updated information.

There are several methods that can be used, however, the method used and results

should be documented. No one method is prescribed but the method and logic used

will be thoroughly documented to the degree that it is repeatable.

If Yes (Change in outcome)

If No (No change in outcome)

Continue to “(I) Update PS-BCA”

Continue to “(E) MFR to MDA”

I

Update PS-BCA

Update the PS-BCA using the most current data available. As the system progresses

through the life cycle, additional data will become available. If the previous PS-

BCA was based predominately on analogous systems, the update should replace

analogous data with actual data. Since the outcome has changed, this should require

reviewing all areas within the PS-BCA (i.e., costs, benefits, and risks). Incorporate

any new information (e.g., extension of the service life since the last PS-BCA) that

has come available since the previous PS-BCA was completed and update ground

rules and assumptions as appropriate.

Continue to activity (F)

F

Develop Recommendation

Summarize the findings in a clear and concise manner that explains the

recommended solution and why it is recommended. Make reference to the other

COAs and how they compare to the recommended COA in costs, benefits, and risks.

The recommendation should be specific, comprehensive, measurable, consistent,

accurate, timely, unbiased, and achievable.

Continue to activity (G)

G

Program MDA Decision Point

Present the recommendation to the MDA for approval. The MDA should document

the rationale for the PS-BCA final decision. This final decision documentation

serves as an archive, and combined with the PS-BCA, provides the baseline for the

next iteration of the PS-BCA. The MDA decision provides closure to the process

and initiates the transition to the selected PSS. MDA documentation (MFR to MDA)

and updates should be annexed within LCSP.

Process ends after this step.

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 25

Step

What Happens

❻ REVIEW INPUT; MORE CURRENT DATA AVAILABLE?

E

MFR to MDA / Document in LCSP

Prepare a memo for the record that documents the results of the analysis performed.

This include rationale includes assessment of affordability and effectiveness of the

program. This documentation should be included in an annex within the LCSP.

MDA documentation and updates should be annexed within LCSP. Attachment 2

provides a sample Legacy Program PS-BCA Sufficiency Memo. Process ends after

this step.

Process ends after this step.

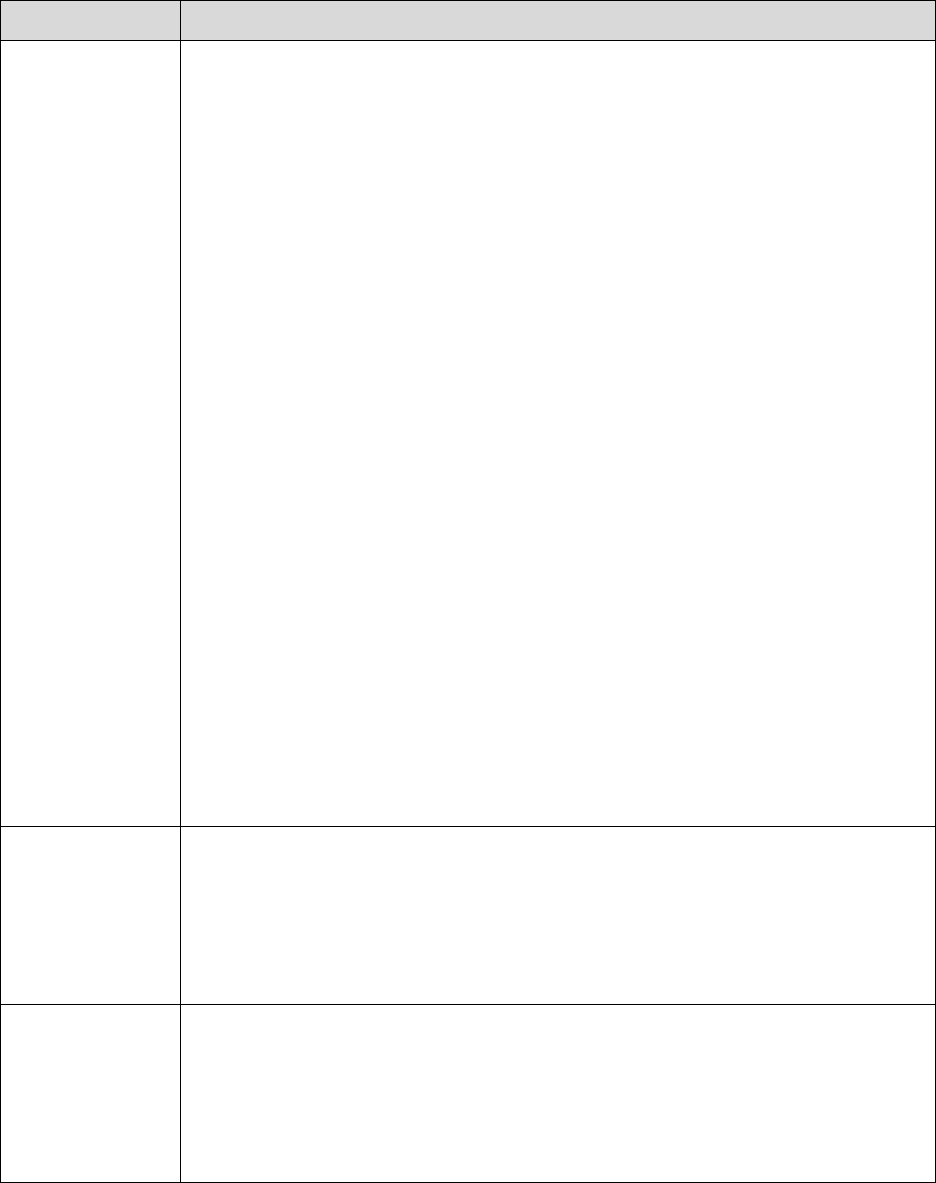

1.5. PS-BCA Process Overview.

1.5.1. PS-BCA Process Map. The PS-BCA process map shown in Figure 1.10 assists the

PMO in identifying the individual steps of the PS-BCA process. Greater fidelity of the PS-

BCA process is described in Attachment 3.

Figure 1.10. PS-BCA Process Map.

26 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

Chapter 2

ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

2.1. PS-BCA IPT Members. Developing a PS-BCA represents a major effort that involves

comparing a variety of COAs in order to support major resource decisions in an effort to obtain

the best value for the product support strategy. Given the scope, scale, and complexity involved,

participation is required from a number of stakeholders (to include the warfighter), support subject

matter experts (SMEs), and advisors. The consolidated participants are led by the PSM and are

referred to as the PS-BCA IPT. The IPT should include major command/Field Command

(MAJCOM/FIELDCOM), Headquarters Air Force (HAF) and United States Space Force (USSF)

representatives. Additional information on the roles, responsibilities, and functions of the PS-

BCA IPT are located in paragraph 2.5.

2.2. Approval Level. The approver of the PS-BCA is the MDA. Depending on the scope and

sensitivity of the decision, the MDA can be the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition,

Technology and Logistics (USD (A&S)), Head of the DoD Service Component, Service

Acquisition Executive (SAE), or Program Executive Officer (PEO). Additionally, the MDA can

delegate the responsibility to make the PS-BCA final decision as outlined in section 2.3 and

maintain compliance with AFI 65-501 and AFMAN 65-506.

2.3. Milestone Decision Authority (MDA). The MDA has overall responsibility for the

acquisition program. The MDA has the authority to approve the entry of an acquisition program

into the next phase of the acquisition process and is accountable to authorities such as Congress

for costs, schedule, and performance. The MDA is based on ACAT levels as listed below:

ACAT ID and ACAT IAM: USD (A&S) or as delegated.

ACAT IC and ACAT IAC: Head of the DoD Service Component or, if delegated, the

SAE (not further delegable).

ACAT II: SAE or the individual designated by the SAE.

ACAT III: Designated by the SAE. This category includes Automated Information

System (AIS) programs that do not meet the criteria for MAIS programs.

2.3.1. Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics (USD (A&S)).

The USD (A&S) is responsible for supervising the Defense Acquisition System. The USD

(A&S) is the principal staff assistant and advisor to the Secretary of Defense and the Deputy

Secretary of Defense for all matters concerning acquisition.

2.3.2. United States Air Force Service Acquisition Executive (SAE). The USAF SAE, also

known as the Component Acquisition Executive (CAE), is responsible for all Air Force

research, development, and acquisition activities in accordance with DoDI 5000 series

directives. This executive provides direction, guidance, and supervision of all matters

pertaining to the formulation, review, approval and execution of acquisition plans, policies and

programs. The SAE can serve as the MDA on ACAT IC programs, if delegated, and

recommends decisions on ACAT ID programs. The SAE represents the Air Force to USD

(A&S) and Congress on all matters relating to acquisition policy and programs.

2.3.3. Program Executive Officer (PEO). The PEO is responsible for cost, schedule and

performance in an acquisition program and/or portfolio. Additionally, the PEO ensures PMs

are coordinating with appropriate stakeholders and representatives to develop capabilities

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 27

based requirements, technical level architectures, integrated test plans, technology transition

plans, product support strategies, and acquisition strategies throughout the entire life cycle.

The PEO validates the PMs’ recommendations and implementation plans. Validation answers

the question, “Is it the right solution to the problem?” A PEO is typically delegated as the

ACAT II and III MDA for programs in their portfolios. The PEO may delegate ACAT III

MDA authorities to any appropriately qualified individual(s). In addition, the PEO, or their

delegate, chairs the Executive Level Incremental Approval Point (IAP) sessions.

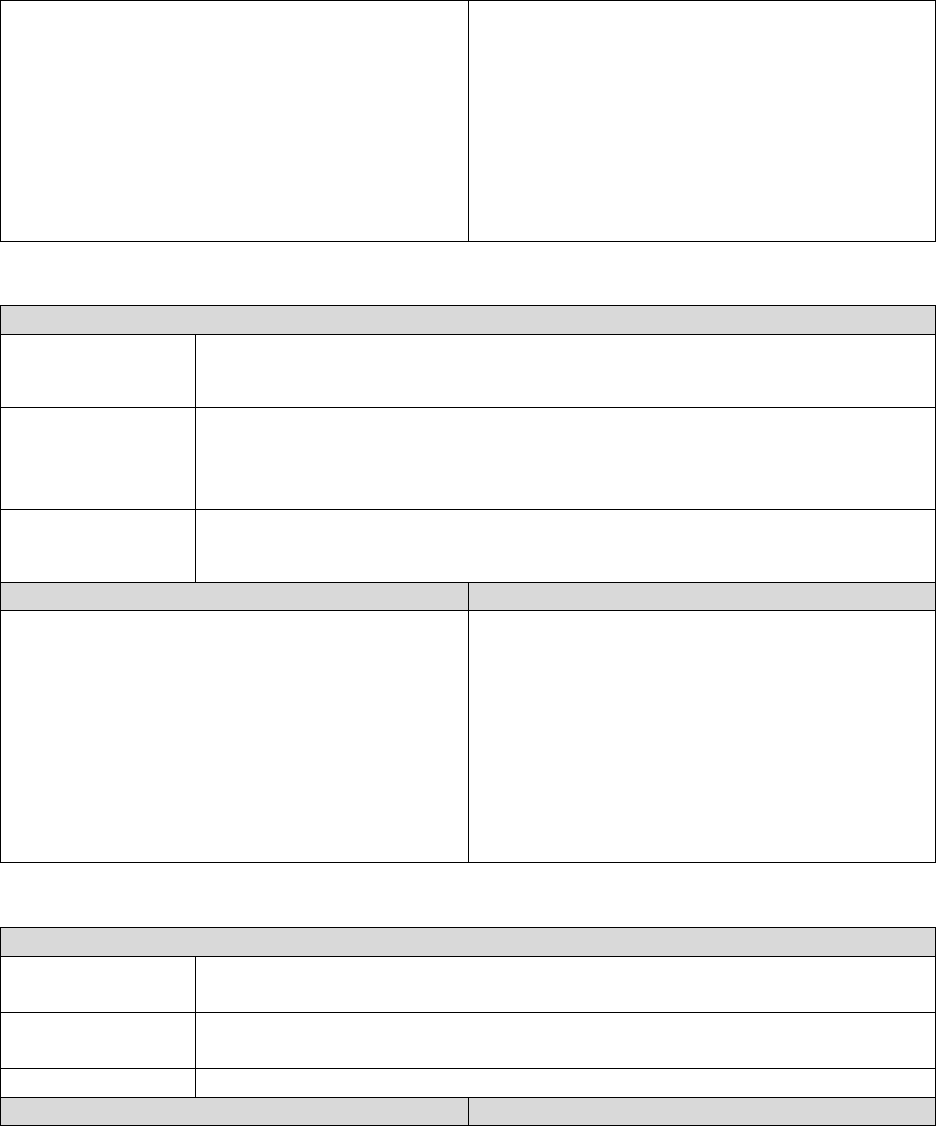

2.4. Governance Structure. For ACAT I (MDAP or MAIS) and selected Office of the Secretary

of Defense (OSD) programs, the coordination/approval structure depicted in Figure 2.1 below

should be followed during the development, review, and approval of the PS-BCA. The PMO is

responsible for identifying a coordination approval structure for the PS-BCA that is commensurate

with the ACAT level of the program. The PMO may leverage existing boards or steering groups

or utilize an existing MDA chain as final review and approval authority for the the PS-BCA. Prior

to the PS-BCA kick-off meeting, the PMO also identifies organizations (i.e., recommended

stakeholders) that should participate in the IAP steps to ensure enterprise level requirements are

addressed. In addition, IAP reviews should be leveraged to ensure “buy-in” throughout the PS-

BCA development process.

2.4.1. PS-BCA Engagement. The following section provides the PS-BCA team insight to

ensure a wide range of diverse perspectives prior to and in support of making major decisions.

The people and organizations representing this diversity are the foundation for governance,

validation, and approval type bodies. Figure 2.1 depicts the governance structure for

MDAP/MAIS ACAT I and special interest OSD programs. Figure 2.2 depicts the governance

structure for ACAT II & III programs.

2.4.1.1. DoD Policy: An acquisition program is categorized based on the criteria in DoDI

5000.02. All defense acquisition programs are designated by an ACAT (i.e., I through III)

and type (e.g., MDAP, MAIS, or Major System). Once an ACAT is established, it remains

throughout the lifecycle of the program. Once sub-programs are incorporated into system

level, all expenditures are included into the higher level system.

2.4.1.2. For ACAT I (MDAP or MAIS) and selected OSD programs, the governance

structures depicted in the Figure 2.1 should be utilized by the PMO during the

development, validation, and approval of the PS-BCA.

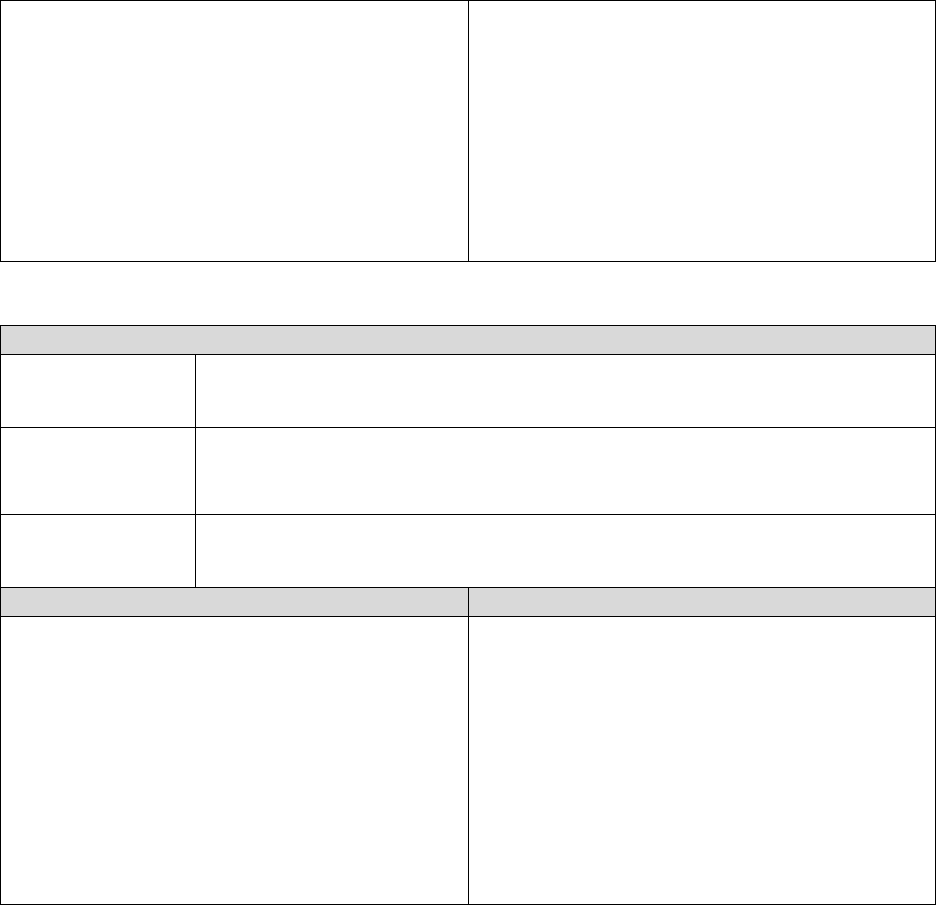

2.4.1.3. For ACAT II/III programs, the coordination/approval structure depicted in Figure

2.2 below should be followed during the development, review, and approval of the PS-

BCA.

28 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

Figure 2.1. MDAP/MAIS ACAT I and Special Interest OSD Programs.

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 29

Figure 2.2. ACAT II and III Programs.

2.4.2. Defense Acquisition Board (DAB). The Defense Acquisition Board (DAB) is the senior

advisory board for the DoD acquisition system and provides advice on critical acquisition

decisions. The board is chaired by the USD (A&S) and includes the Vice Chairman of the

Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Service Secretaries, and a number of Under Secretaries of Defense.

Members of the DAB are responsible for approving MDAPs and serve as the most important

executive review of expensive acquisition projects in the DoD. The DAB is also the principal

review forum enabling USD (A&S) to fulfill 10 USC Chapter 144 responsibilities concerning

ACAT I programs.

2.4.2.1. Best Practice: Presenting/coordinating the PS-BCA recommendation to the

appropriate stakeholders/advisors and within the chain of command is the responsibility of

the PMO. While not technically in the PM-PEO-MDA chain of command, it is

recommended for all ACAT IC/D and ACAT IAC/AM programs to ensure product support

validation within sustainment command centers prior to making recommendation to the

SAE. (e.g., Programs within Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC) should ensure Air

Force Sustainment Center (AFSC) / Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC)

30 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center (AFNWC) commanders are presented with the PS-

BCA recommendation.) Coordinate ACAT IC programs with SAF/FMC per AFI 65-501.

2.4.3. Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Acquisition) (SAF/AQ). The SAF/AQ has the

authority, responsibility and accountability for all Air Force acquisition programs and for

enforcement of USD (A&S) procedures. The SAF/AQ may choose to enact a decision based

on their inherent knowledge of a program for ACAT IC, ACAT IAC, and ACAT II programs

(if not delegated).

2.4.4. Incremental Approval Points (IAPs). IAPs are vector checks designed to provide

directional guidance and concurrence throughout the process on such matters as the scope,

GR&A, evaluation criteria, problem statement, COA selection, data sources, risk mitigation

strategies, and all other critical factors contained within the PS-BCA. IAPs ensure the PS-

BCA strategy integrates an enterprise wide perspective. IAPs help identify and gain

concurrence on key GR&As, constraints, and most notably the weighting and scoring

methodology. IAP members are determined by the impact and level of the decisions being

made, as well as the PSM’s chain of command.

2.4.5. IAP Frequency. There is no limit for the number of IAPs during development of the PS-

BCA. Discretion as to how many IAPs to conduct is left to the PSM. The PSM needs to ensure

all aspects of the PS-BCA are well communicated and shared with appropriate stakeholders,

SMEs, and advisors. The PSM should have this governance body in mind when developing

the PS-BCA. These periodic meetings, and/or coordination activities, should ensure that no

stakeholder or approval authority is surprised by the final PS-BCA recommendation.

2.4.5.1. Executive (GO/SES) Level Incremental Approval Point. The Executive General

Officer/Senior Executive Service (GO/SES) level IAP includes multi-functional senior

executives who provide an enterprise perspective to enhance decision making for the

MDA. The Executive IAP members provide senior level review balancing requirements,

resources, priorities, and mandates. Executive IAP members also provide guidance to the

acquisition execution chain from an integrated and enterprise perspective. This includes

providing insight and ensuring statutory and regulatory compliance and providing support

to the PS-BCA team as requested. The PEO may choose to utilize existing command 1-

Star governance boards or virtually coordinate with the Executive IAP members.

Executive IAP members include, as applicable:

2.4.5.1.1. PEO

2.4.5.1.2. Directorate of Logistics and Product Support (SAF/AQD)

2.4.5.1.3. Directorate of Information Dominance (SAF/AQI)

2.4.5.1.4. Directorate of Global Power (SAF/AQP)

2.4.5.1.5. Directorate of Global Reach (SAF/AQQ)

2.4.5.1.6. Directorate of Cost and Economics (SAF/FMC)

2.4.5.1.7. MAJCOM A4 A5/8/9 Engineering (EN), Contracting (PK), Financial

Management (FM) (or USSF equivalent)

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 31

2.4.5.1.8. Center LG (Space Systems Command (SSC)/Air Force Life Cycle

Management Center (AFLCMC)/Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center (AFNWC)/Air

Force Sustainment Center (AFSC))

2.4.5.1.9. Space Systems Command (SSC)/Space Logistics Directorate (S4)

2.4.5.1.10. Others as required by PEO

2.4.5.2. O-6/GS-15 Level Incremental Approval Point. The multi-functional O-6/GS-15

IAP reviews the GR&A, constraints, and weighting/scoring criteria and advises on the

authoritative data sources used by the PS-BCA IPT to conduct the financial and non-

financial analysis. The criteria for the authoritative data source should be: accurate,

comprehensive, consistent, timely, available, and accepted. This approval step may occur

numerous times in the course of the PS-BCA process as data sources are revealed as

determined by the PM. The O-6/GS-15 IAP members include, as applicable:

2.4.5.2.1. PM

2.4.5.2.2. MAJCOM A4 A5/8/9 Engineering (EN), Contracting (PK), Financial

Management (FM) (others as required)

2.4.5.2.3. Center LG (SSC/AFLCMC/AFNWC/AFSC)

2.4.5.2.4. End-User

2.4.5.2.5. Others as required by the PM

2.4.5.2.6. SAF/AQD (Only ACAT I / Select OSD Programs)

2.4.5.2.7. SAF/AQ (I, P,Q) (Only ACAT I / Select OSD Programs)

2.4.5.2.8. SAF/FMC (Only ACAT I / All OSD Programs)

2.5. PS-BCA IPT Roles, Responsibilities, and Functions. The following section provides

guidance on assembling a PS-BCA IPT. The section addresses involving the right stakeholders,

support SMEs, and advisors at the kickoff meeting and assembling the governance structures. A

PS-BCA is a team effort undertaken by experienced participants across a wide range of specialties.

From the initial stages of accomplishing the background research and gathering the data, through

the final stages of staffing a PS-BCA for senior decision makers, completing an effective PS-BCA

requires significant effort by all those involved.

2.5.1. PS-BCA IPT Structure. Product support encompasses a range of disciplines including,

but not limited to, logistics, requirements, operational mission planning, financial

management, contracts, legal, and integrated product support elements. The structure of the

PS-BCA IPT varies depending on the maturity and the mission of the program. The PSM

should be cognizant of where the program is in the life cycle, understand the major

milestones/events, and provide useful information to the decision makers for the program to

move successfully forward through the life cycle. The team should leverage the cross-

functional expertise of its members to ensure all support COAs are considered and the best

value PSS is selected.

2.5.2. PS-BCA IPT Characteristics. PSS are comprehensive and require early and frequent

discussion and planning efforts across and between all key stakeholders and advisors. An

effective PS-BCA IPT has these characteristics:

32 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

All functional disciplines influencing the weapon system throughout its lifetime are

represented.

All the members buy into the team's goals, plans of actions and milestones,

responsibilities, and authorities.

All staffing, funding, and facilities requirements are identified and resourced.

2.5.3. PS-BCA Role and Responsibilities. The following sections describe roles and

responsibilities of key IPT members that may be involved in the PS-BCA depending on the

program’s life cycle phase. The PMO should maintain an IPT membership plan which should

use all of the information collected to lead IPT membership. The IPT membership plan is a

key component of executing and completing a successful PS-BCA. A large portion of IPT

management focus is on communication. The cornerstone of stakeholder and advisor

management is understanding who needs what information and when or how often they need

it. The PS-BCA process map (see Figure 1.10) incorporates relationships between activities

and functional units. This diagram focuses on the logical relationship of the value activities

and shows opportunities for open dialogue across multiple levels. The various stakeholders

representing organizations, SMEs, advisors, approval authorities, etc. should all work together

from the initial development of the problem statement through the final PS-BCA report

incorporating the MDA decision and attaching the PS-BCA to the LCSP.

2.5.3.1. Program Management Office (PMO). The PMO staff assists the PM and PSM in

developing the PS-BCA. Within the PMO, the PSM is responsible for planning,

developing, implementing, and executing the PSS, informed by the PS-BCA. Each

member of the PMO staff should actively participate in the PS-BCA kickoff meeting and

in developing the scope, GR&As, and problem statement. PS-BCA roles and

responsibilities should generally remain consistent regardless of whether the role is

performed by a government employee or a contractor, but ultimately the PMO staff is

responsible for the content and PS-BCA deliverables.

2.5.3.1.1. The PMO staff should determine what individuals or groups can influence

and affect the PS-BCA or be affected by its performance and outcome. IPT member

identification is the process used to identify all stakeholders, SME support, and

advisors for a PS-BCA. It is important to understand that not all IPT members have

the same influence or effect on a PS-BCA, nor will they be affected in the same manner.

There are many ways to identify IPT members, however, it should be done in a

methodical and logical way to ensure that IPT members are not easily omitted. The

selection process may be done by looking at IPT members organizationally,

geographically, or by involvement with various phases or objectives. Another way of

determining IPT members is to identify those who are directly impacted by the PS-

BCA and those who may be indirectly affected. Examples of directly impacted IPT

members are the project team members or the MAJCOM who directed the PS-BCA is

being done for. Those indirectly affected may include an adjacent organization or

members on the local community. Directly affected IPT members should usually have

greater influence and impact of the PS-BCA than those indirectly affected.

2.5.3.1.2. Support contractors (extension of the PMO) may participate in the PS-BCA

IPT, but they cannot commit the PMO they support to a specific position. The PMO is

responsible for ensuring support contractors are employed in ways that do not create

the potential for a conflict of interest. Contractor support staff may participate in PS-

DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022 33

BCA IPT discussions, however, they are not permitted to represent the position of the

supported organization and it is recommended they be asked to sign non-disclosure

agreements prior to deliberations. The PMO should consult with the legal advisor to

determine whether an organizational conflict of interest exists.

2.5.3.2. Program Manager (PM). The owner of the PS-BCA is the PM and he/she is the

primary initiator of the actions and recommendations derived out of the PS-BCA. The PM

also obtains the resources necessary for accomplishing the PS-BCA.

2.5.3.3. Product Support Manager (PSM). While the PSM reports directly to the PM,

he/she has statutory responsibility, per 10 USC §2337, to lead the PS-BCA. This includes

overseeing the team that is conducting and writing the PS-BCA. The OSD PSM guidebook

and the DoD PS-BCA guidebook can assist the PSM in defining the roles and

responsibilities of the team members. PSMs are also responsible for managing support

functions required to field and maintain the readiness and operational capability of major

weapon systems, subsystems, and components. Ultimately, the PSM serves as the overall

lead for the development of the PS-BCA:

Responsible for assembling the governance structure, appropriate board members,

stakeholders, support SMEs and advisors

Identify PS-BCA IPT members (to include Contractors, Original Equipment

Manufacturers (OEMs), depot/operations/logistical units)

Key player in the problem statement development and approval

Provides insight on support strategy and integration of the IPSEs.

Key player on development of COAs and identification of data sources

2.5.3.4. Data Manager. One of the primary responsibilities of the data manager is

maintaining and keeping historical records of PS-BCAs. These records include research,

performance outcomes, cost estimates and methodology, and sources of data. Effective

configuration management of acquisition documents supports the decision making

processes by allowing decision makers to have information available throughout the

present and future PS-BCA process. The functions a data manager performs can be

accomplished utilizing existing resources. Some members of the PS-BCA may perform

multiple roles and responsibilities.

2.5.3.5. Cost Analyst. The cost analyst has the training and skills to develop the

financial/cost analysis section, the analytical methodology for the PS-BCA, and

comparative analysis of both quantitative and qualitative factors for each COA. The cost

analyst works with the budget analyst who analyzes historical funding and develops the

budget plan with regards to the recommended PS-BCA approach. The cost analyst

prepares and organizes the PS-BCA cost estimate in accordance with (IAW) applicable

AFI, AFMANs, OSD, and Office of Management & Budget (OMB) guidance, actively

participates in the formation of the cost scope and baseline, and performs PS-BCA

calculations to include life cycle cost estimates, benefit analyses, risk assessments,

affordability, and sensitivity analyses. The cost analysis is a primary duty of the PS-BCA

IPT and highlights the cost differences between support or sustainment strategies. PS-

BCA cost analysts should follow the cost estimating guidance outlined in the DoD “Cost

Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) Operating and Support Cost Estimating

Guide (September 2020).”

34 DAFPAM63-123 14 APRIL 2022

2.5.3.6. Logistician (Requirements, Logistics, and Supportability Manager). The

logistician is responsible for ensuring the sustainment strategy, requirements, and

performance measures are in the PS-BCA. The logistician also provides COA specifics

and ensures sustainment requirements are comprehensively met. Additionally, this person

is responsible for completing the mission impact section, including the non-financial

analysis of the PS-BCA as well as collecting and calculating system/program logistics

metrics such as failure projections, operating hours and sparing requirements. The PMO

may have to obtain Space Operations Command (SpOC), Headquarters Air Force Materiel

Command (HQ AFMC) or AFSC SMEs for Supply Management, Deployment/

Distribution/Transportation, Maintenance support, and Life Cycle Logistics (LCL)

expertise.

2.5.3.7. Chief Engineer. The Chief Engineer and the PSM work together to align the